As Gittin draws to a close, the final Mishna (90a) discusses what would justify a man divorcing his wife. A Biblical verse about divorce, Devarim 24:1, states כִּי מָצָא בָהּ עֶרְוַת דָּבָר, “for he found an unseemly matter in her.” Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel argue about the implications of the עֶרְוַת דָּבָר, whether it needs to relate to immorality (Beit Shammai) or just that she burned the food (Beit Hillel). Then, Rabbi Akiva endorses no-fault divorce, saying even if he finds someone else better looking than her, as the preceding phrase in the verse was וְהָיָה אִם לֹא תִמְצָא חֵן בְּעֵינָיו, “and it will be, if she doesn’t find favor in her eyes.”

Derasha Mechanics

I wonder how Rabbi Akiva’s derivation operates. Is it merely a matter of simple peshat, that any reason she no longer finds favor will suffice, with the later clause about finding עֶרְוַת דָּבָר as non-binding, but merely an alternative? This is how the Talmudic Narrator explains the dispute between Beit Shammai and Rabbi Akiva (and according to a printing/some manuscripts, also Beit Hillel). The Narrator invokes Reish Lakish, who elsewhere says that the word כִּי can designate one of four things: אי / if, דלמא / perhaps, אלא / rather, and דהא / because. I say the Narrator invokes because the Narrator takes care to lay it out with duplicative language, בִּדְרֵישׁ לָקִישׁ – דְּאָמַר רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ. We see the same way of invoking Reish Lakish in Taanit 9a / Rosh Hashanah 3a, supporting Rabbi Abahu’s revocalization of ויראו so that the Israelites didn’t only see, but were were seen, as a result (דהא / because) of Aharon’s passing and the resultant removal of the Clouds of Glory. And Reish Lakish is similarly invoked in Shevuot 49a, to help bolster Rabbi Ami, who interprets the ki of א֣וֹ נֶ֡פֶשׁ כִּ֣י תִשָּׁבַע֩ לְבַטֵּ֨א בִשְׂפָתַ֜יִם to mean אי / if. I have no idea where the primary sugya with Reish Lakish is, and in what context he really said it.

For the application in Gittin, Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel can understand it as “because.” Our printed text states that Rabbi Akiva understands it as אִי נָמֵי, מָצָא בָהּ עֶרְוַת דָּבָר, “alternatively, he found an unseemly matter.” If it really means אִי נָמֵי, or as most manuscripts have it, a single word אִינָמֵי, then it is a kvetch of Reish Lakish, for Aramaic אִי by itself means just “if,” and in Shevuot it was invoked as אִי to only mean “if.” We could argue, like Rashi, that indeed it means “if,” but this אם matches the אם earlier in the verse, אִם לֹא תִמְצָא חֵן בְּעֵינָיו. The two conditionals work in parallel, with a logical or, rather than as a logical and. Meanwhile, reading it as “because” would subordinate the second conditional to the first, so both must be true.

Because I’m always on the search for the hidden derasha, I noticed that the Mishna asks what was found. For Beit Shamai, he “found” an immoral matter. For Beit Hillel, it was any matter that he nonetheless discovered. For Rabbi Akiva, he also “found” something—a woman prettier than her. Indeed, the cited prooftext is the word earlier in the verse, תִמְצָא. I would argue that the reading is: she, his current wife, doesn’t find favor in his eyes. מִכְּלַל לָאו אַתָּה שׁוֹמֵעַ הֵן, from the negative you deduce the positive. She didn’t find favor, but another woman did find favor. In turn, that is why he now dislikes his wife, expressed as מָצָא בָהּ עֶרְוַת דָּבָר. I don’t think ki would mean “if.” Rather, it would mean “rather.”

A Fly in the Drink

While we’re discussing comments which may offend, let’s discuss Rabbi Meir who notes (Gittin 90a, Tosefta Gittin 5:9) three types of men. The first, a fly falls in his cup and he throws out both the wine and the fly. The second, a fly falls in his cup, so he fishes out the fly and drinks the wine. The third, a fly falls in his serving bowl (tamchuy), and he squeezes out the fly and eats it (namely, the food). Rabbi Meir draws analogies to husbands and how they would allow their wives to relate to other men—see inside.

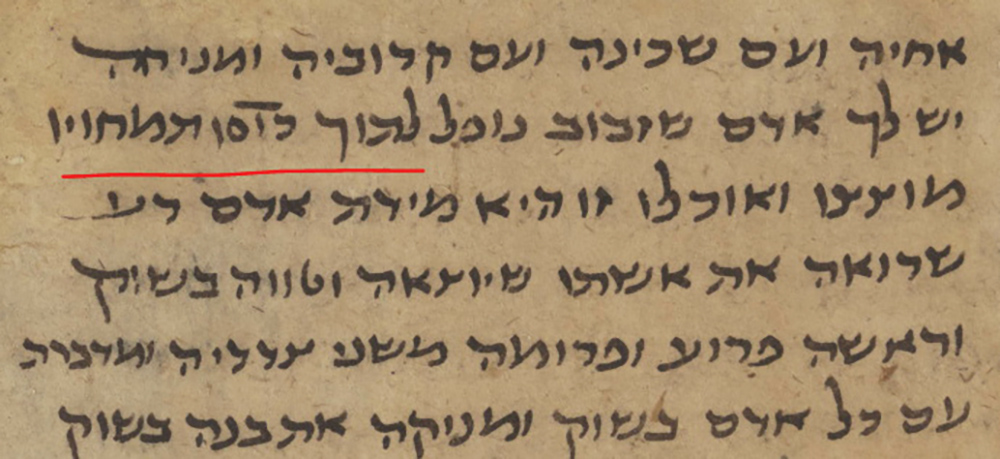

I don’t understand why there was a shift from cup to bowl in the third instance. He could have squeezed out the liquid and drunk the wine. Indeed, the Lewis-Gibson Talmud 2.27 manuscript has כוסו, perhaps by dittography, then overstrikes it and writes תמחויו. The following verb is אוכלו.

I’d speculate with little evidence other than this cross-out that it should indeed be his cup, but the אוכלו originally referred to the fly. Then, since one cannot eat wine, cup turned to bowl.

Chazal elsewhere consider finicky drinkers. Rashi to Bereishit cites Bereishit Rabba 88:2 that the sin of Pharaoh’s butler was that a fly got into Pharaoh’s drink. But we see the idea in other cultures as well.

Rabbi Meir’s tale of three measures of man made its way into an offensive ethnic joke, which I relate because of its scholarly value, rather than any animus towards any ethnicity: An Englishman, Irishman and a Scotsman walk into a pub. A fly lands in each of their drinks. The English man refuses to drink; The Irishman blows the fly off the foam and proceeds to drink; The Scotsman picks the fly up by the wings, holds it over the drink, and shouts “Spit it out, ya wee mamzer!”

So too, there’s a Sunnah of Mohammed, in Sahih Bukhari 4:54:537, “It was narrated from Abu Hurairah that the Prophet said: If a fly falls into your drink, dip it into it then throw it away, for on one of its wings is a disease and on the other is a cure.” So, here is a fourth approach! By the way, it’s interesting to see the Islamic equivalent of kiruv and apologetics justifying this as scientific.

Who got it from whom? There’s no question that Rabbi Meir precedes both the ethnic joke and Mohammed, so we didn’t get it from them. However, I suspect that Rabbi Meir is channeling an existing joke or tale from the surrounding culture in order to better express a Torah perspective as it pertains to marriage.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.