The Atlantic Ocean has for centuries served as a massive communication link between continents. Its waves lap upon North and South America, Africa, Europe, and the Polar regions. Millions in the past have braved wind-tossed crossings to start new lives on one shore or another. Today, of course, planes cross the watery wastes in hours. Throughout history some objects have taken much too long to make the crossing. This story is about one such case, a surprising tale of kindness and honesty that is hard to believe but true.

The outbreak of World War II in the West in May 1940 came on like a plague of locusts, a fast-spreading epidemic affecting the victim nations over a period of hours, days, and weeks. In those countries proximate to Germany, conditions worsened rapidly. As one would expect, those individuals more firmly established in their pre-war lives were often least likely to possess the mobility to drop everything and run–the natural response to life-threatening action by an enemy bent on conquest. The elderly, the very young, and young families were in the majority, tragically, unable or unwilling to flee.

Other members of families were far from home when war broke out that spring. Still others had been mobilized to serve in their respective armed forces. Among the latter was my father, Maurice, a 26-year-old private in the Belgian Army. At the time of the outbreak, he was assigned to a Belgian infantry unit serving in Northern France under the joint commands of England, France, and Belgium. With only the most basic training, Maurice was tasked with defending his country against elite German troops. Two weeks into the conflict, he awoke to be informed by his commanding officer that the Belgian government had capitulated to the Germans and that all Belgian combatants were free to go wherever they wished. It was 6:00 a.m. on May 24th and Maurice was stationed in the town of Abbeville, not far from the English Channel coast. It was rumored that elements of the VII Panzer Corps were in the vicinity so Maurice and some of his compatriots headed south on foot. It turned out to be a fateful decision to travel in that direction as Panzer units in fact arrived in Abbeville at 6:00 p.m. that evening. At this point, in a mysterious move still unclear today, the Germans stopped their advance. This step allowed some 300,000 Allied troops to escape from the French port of Dunkerque by ship while the Germans dawdled.

Maurice did not dawdle. After barely escaping the Germans, he mapped out a plan to outrun the enemy (they were not in fact pursuing him) and headed in a southwesterly direction toward the Atlantic ports of Bordeaux and Bayonne-Biaritz. On foot, the trip of 500 kilometers (300 miles) would take him more than a month, what with the narrow roads crowded with thousands of refugees heading south with him. While not advancing on the ground, the Germans harried the civilians with unending dive-bomber attacks; the Stukas controlled the skies over France and they terrorized the many exposed on these roads.

In light of these conditions, Maurice decided he would buy a bicycle to speed his journey south. After a day of searching for a suitable vehicle, he lucked out when a farmer offered to part with an extra bike he wished to convert into cash. Maurice mounted his new transport and set out the next morning in the direction of Tours.

At this point it is important to our story to realize that in these early, chaotic days of the war, the Germans, though successful from a battlefield perspective, could hardly be said to “control” the lands they had conquered. They might have commanded important crossroads and accepted the surrender of combatant armies, but much of the infrastructure they had attempted to destroy remained in place at least for several months before the occupation began in earnest. Thus, Maurice in the French countryside was able to communicate with his family in Antwerp while he made his way south. In no uncertain terms, his mother instructed him not to return to Belgium. She sensed the danger even though she was unaware of the full scope of the destruction that ultimately awaited her.

She knew Maurice’s older brother Jos had arrived safely with his young wife in America in 1939 and that her older son Jack had left Antwerp as well, and she hoped he too would ultimately escape to America. Maurice heeded his mother’s words and continued to advance towards the Atlantic Coast of France.

After two weeks of hard pedaling, Maurice arrived at the bustling port of Bayonne. His first need was to find some lodging and some kosher food. The Jewish population of Bayonne totaled a mere 300 souls, but that number had been hugely augmented by hundreds of French and Belgian Jewish refugees; Maurice was able to join a network of fellow escapees from Antwerp who he found at the local synagogue. Several of the new arrivals had heard there was work available at the docks, since most of the young French workers had gone to the front to defend France. Maurice headed down to the busy wharves and soon found work toting 40-kilo (88-lb) sacks from cargo ships into adjacent warehouses. After two days of this backbreaking work, Maurice convinced the foreman that he had “office” experience and was assigned the job of counting the sacks that others carried into the storeroom. That daring move probably saved him from doing lifelong damage to his back, not to mention that the office staff made several francs more a week in wages.

After two weeks in Bayonne, it became clear that Western France would not remain a haven for Jewish refugees for long. Maurice began to pay closer attention to the varied ships that came to the harbor, ships that were merely stopping at Bayonne, picking up supplies and fuel, before continuing on to exotic North African locations: “Morocco, Agadir, Mogador, Casablanca, Marrakech!” Maurice had heard or read about these places in books, but they now appeared to be his only option to escape the Continent. Having accumulated the steerage fare for one such trawler, Maurice boarded the ship early one morning in May for North Africa and the mysteries of Morocco.

Eight days later, Maurice stepped ashore at the dock at Casablanca, fabled port of intrigue and spies. All he knew of the city was from books and movies. The Casbah, the Berber ruins, the myriad languages spoken in the souq, the international flavor all made this city a unique travel destination at any time. In wartime, however, as a French colony, the city mirrored the divisions that were occurring at that very moment in France itself. With the fall of the mother country, the Moroccan populace was rapidly beginning to choose sides between those happy to collaborate with the Germans and those loyal to the “Free French.” Maurice inquired at the docks about where he might find a synagogue or, failing that, any representative of the local Jewish community. He was happy to discover that the main synagogue was just a short distance from the port area and he immediately started in that direction.

In 10 minutes he stood before a two-story building with a weathered sign in front that read: “Communate des Juifs de Casablan.” The door was open and inside sat a tanned older man at a desk cluttered with papers. Maurice introduced himself to the man, speaking in the French every Belgian was fluent in. The man, Eduardo Sasson, was the director of the Jewish Community of Casablanca, and he welcomed Maurice warmly. He apprised him of the situation locally for Belgian Jews and suggested he make the acquaintance of a certain Alphonso Sabah, who was a useful contact for refugees such as Maurice.

Sabah was a Jewish merchant from Tangiers who was well connected at the highest levels of the Moroccan government. If anyone could assist Maurice, he would be the man. Sasson wrote a short note of introduction, and handed it to Maurice, along with an address and phone number where Maurice could locate Sabah.

That evening Maurice met with Sabah, and they immediately bonded in those mysterious ways that one reads about in stories. Sabah, 35 years old, handsome, a devoted, Zionistic leader of the Moroccan Sephardic Jewish community and Maurice, an Ashkenazic refugee on the run, from a family rooted in Eastern European traditions, saw something in each other that resonated and this chance meeting would flourish into a life-long friendship.

“Maurice, you know we need educated Jews such as yourself here in French Morocco at this perilous time to help administer the country and assist our community. You may not be aware that while the national language is Arabic, the rulers of Morocco are Berbers, not Arabs, and our community is highly regarded by the King and his Prime Minister, El-Glowi, the Pasha of Marrakech. Luckily, I am meeting with the Pasha tomorrow and his captain of the guard. I’m willing to take you to this audience and introduce you to these important people. It would be useful for you to meet them.”

Maurice didn’t know what to say. He had hardly a couple of francs in his pocket and his clothing was threadbare. He didn’t speak for a moment.

“I was told by my brothers that they were trying to arrange for a visa for me to the U.S., which would be waiting for me in Lisbon. If you could help me contact them, I would be much obliged. And, of course, I would like to accompany you to meet the Pasha!”

“You will stay at my house this evening,” Sabah offered. Meanwhile, here is some money so you can get something to eat.”

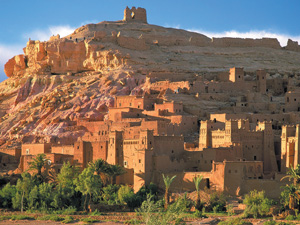

The next morning after prayer, Maurice left with Sabah for the three-hour drive to Marrakech and the foothills of the snow-capped Atlas Mountains. The weather was clear, the terrain alternating desert vistas and shrub-filled wilderness landscapes. If Casablanca was mysterious to a European, Marrakech was stepping back into another time altogether.

This was a city of caravan routes, of oases and French Foreign legionnaires; the city’s minarets crowded the sky and dwarfed the ancient Jewish ghetto or mellah. The meeting with the Pasha was scheduled for 3:00 in the afternoon, so Maurice had about two hours to wander about the narrow-streeted Jewish quarter and soak in the atmosphere. He felt transported back centuries in time when he heard the distinctive Muslim call to prayer of the muezzin from high above the city. He had to suppress the urge to run and hide from invisible assailants brandishing scimitars and knives.

Maurice met Sabah at the appointed time and they entered the Pasha’s palatial offices together. After a brief security check, they were ushered into the office of the Pasha’s chief lieutenant, who embraced Sabah warmly.

“And who is this young man, the official asked?”

“He is the Belgian I told you about. He could be useful to us. Could you appoint him some governmental task so he will stay with us and not flee to America?”

“Young man, Alphonso here asked me to confirm with our connections in Lisbon whether you are on the list for a U.S. visa. Our sources confirm that you are!”

Maurice was more than pleased.

“But that doesn’t mean you have to go. If you agree to remain here, we could provide you with a place to stay, an easy job and even a nice Jewish girl if you desire.”

Maurice was flattered, but he did not readily accept the Moroccan’s offer.

“I really want to join my brothers in the U.S. as soon as I can.”

The Moroccan seemed disappointed by Maurice’s response, but, after a momentary sigh, he changed the subject.

“Let’s go in to see El-Glowi!”

They entered a large hall at the end of which stood a throne-like structured adorned with several large cushions. Atop one of the cushions sat the Pasha, in full Turkish-era dress. He was surrounded by brightly-colored wall coverings and guards armed to the teeth. Several veiled ladies sat on a divan behind him. Maurice thought he was on a movie set and expected the French Foreign Legion to burst into the hall at any minute. The Pasha signaled for the three men to approach. It took a full minute for them to cross the hall and stand directly before the second most powerful man in all of Morocco.

“Hello Sabah, my Jewish friend, how are you? Terrible things going on in Paris, n’est-ce pas?

And who is this young man, may I ask?”

“He is a Belgian Jewish refugee; he was in the army and was lucky to escape the Germans.”

“It must have been horrible, my boy. I’m glad you were able to survive! You know, we could use a good man like you. You could make a good life among us. We can provide you with everything for a good life. Morocco isn’t half-bad, you know!” he joked.

Sabah and the lieutenant informed El-Glowi of Maurice’s earlier rejection of the Moroccan offer. The Pasha smiled upon the news and quickly addressed Maurice for a final time. “I am, of course, saddened by your decision, but I also respect a man who wishes to reunite with his family. Good luck on your journey!”

The audience with the Pasha over, the men withdrew and Sabah and Maurice returned to Casablanca late that night. The next morning, a Wednesday, Sabah sat with Maurice to discuss how the latter would affect his departure from Morocco to Lisbon. Events locally were moving rapidly and the collaborationist Vichy French government was sending their pro-German officials to all French colonies (including Morocco) to replace loyalist officials.

“It is necessary for you to leave for Lisbon as soon as possible, Maurice. Once the Vichy take over, you may find yourself interned in a camp by the Moroccan police or worse, since you are a foreign citizen. I must call my friend in the immigration department to see how we’ll get you out on the next boat to Portugal!”

After several phone calls, Sabah told Maurice to gather his few belongings and accompany him to see the chief of exit transit in the center of Casablanca. Sabah took Maurice to the entrance of the white masonry building and said his farewell.

“This is as far as I can safely go; the building is being watched by unfriendly eyes. I hope we will meet one day in the future when things in the world are not so crazy. Maybe in the land of Israel!”

Maurice could not adequately express his thanks to his Moroccan friend. He promised to never forget him and that they would meet again.

Soon Maurice sat before the man who would decide whether he would be able to leave Morocco. The director was a man in his 50s, with a tan complexion. A tasseled fez sat on a chair near his desk.

“Remove the hat, Monsieur Maurice,” he said, calling him by his first name, “and sit down on the chair, please. You have friends in high places; let me review your papers for a moment.”

Maurice waited apprehensively.

“Ah, ah,––they seem in perfect order! It seems you can be on your way as early as tomorrow. One thing I should like to point out: We have a society in Casablanca that supports widows and orphans and it is customary for departing visitors to donate some small token to this fund to facilitate departure.”

Maurice was not sure what to say or do; he had only one hundred francs on his person that Sabah had given him and he had to book passage to get to Lisbon. Did the director think that perhaps Maurice carried Belgian currency of a different sort (diamonds!)? Maurice had nothing of the kind in his possession. Finally, he reached into his pocket, pulled out a one-franc coin and placed it in the hand of the stunned director. Maurice quickly scooped up the signed, stamped exit visa, thanked the director, and hurried out of the office.

There was no time to delay because the new Vichy director of exit visas was arriving the next day. The only scheduled ship immediately leaving for Lisbon was a Panamanian trawler bound for Portugal carrying a large cargo of bananas. Maurice bought passage and at dawn he was on board for the northward trip of 600 nautical miles. This trawler had absolutely no passenger amenities and, worse, no food to speak of–-just a cargo full of green bananas.

At this point Maurice had adapted greatly to his new life “on the run.” Accordingly, he devised a plan to convert the inedible into the edible. Each night of the 11-day trip, he would take a bunch of green bananas and place them next to his body where overnight his body heat would miraculously ripen the bananas enough to make a suitable meal to get him through the days at sea. Finally, on a foggy day in August 1940, the trawler put in at the port of Lisbon, capital of Portugal on the Iberian Peninsula.

Lisbon would be home to Maurice during the next three months or so. Communications with the U.S. were excellent, so Maurice was able to correspond with his brothers, who sent him details regarding his visa status as well as traveler’s checks as needed. The visa process was more complicated than he had anticipated, but finally, by the beginning of November, he completed all the necessary paperwork to proceed. He booked passage for early December 1940 on a ship called the Serpa Pinta (the Yellow Snake), a formidable five-decked vessel that ferried more war refugees and allied troops safely across the Atlantic throughout the war years than any other civilian vessel. Before he departed, Maurice decided to do one last thing to assist those he loved who were still captive behind enemy lines. A day before he was to depart, Maurice was walking from his hotel in the Baixa district of Lisbon when he came across a small store at which newspapers and sundries were sold. He entered the store and approached the man who stood behind the main counter.

“Do you sell any coffee, sugar or chocolate? If you do, would you be willing to ship such items to other countries if I pay all costs?”

The man nodded yes to both questions.

Maurice took out a list he had been preparing for this moment. On the list were names and addresses of relatives in Belgium, as well as more distant relatives in Poland. Even though the war had been raging for some time in the West and even longer in the East, there was hope that at least some of these posted packages would get through. Maurice made a second list of the items he wanted the man to ship. Maurice asked him to prepare such packages and mail them every two weeks. He gave the man the princely sum of $200 to cover present and future costs. Maurice had wisely saved a large part of the funds sent him by his brother in America. The Portuguese noted the payment in his register and gave Maurice a receipt.

The date of departure from Lisbon soon arrived. Maurice boarded the Serpa Pinto for the 11-day voyage to Philadelphia and, though traveling through U-boat infested waters, arrived safely in the US.

***

Maurice made a rapid adjustment to life in America. He quickly met the love of his life, married in February, 1942, started a diamond-cutting business in Lower Manhattan, and began to raise a large family of daughters all born while WWII continued to rage. He never forgot those individuals who helped him escape the Holocaust, his adventures in Southern France, his Moroccan friend, Alfonso Sabah, the Pasha of Marrakech, even the director of exit visas in Casablanca who requested a “contribution” to the local kitty. The one individual he almost forgot was the Portuguese tobacconist and chocolatier with whom he had arranged to send packages into occupied Europe. Before she was deported to Auschwitz in 1942, Maurice’s mother had written him in America that some of their relatives in Poland had told her they were receiving mysterious packages containing chocolate, sugar and coffee. They had no idea where these desirable packages were coming from, but they were very happy to receive them as was she. Soon all such communications from relatives in Europe ceased. The Germans had turned from military conquest to genocide.

It was early spring of 1946, and New York was just starting to throw off the chill of winter. Maurice returned from work one afternoon and stopped at his mailbox to collect the day’s mail. Among various bills and notices, he found an oddly-marked letter with official looking stamps. The crumpled letter had several Portuguese stamps affixed and a postmark dated April 5th, 1941 alongside the following boldly-stamped legend: HELD UP BY THE BRITISH CENSOR IN BERMUDA

Maurice hurriedly opened the letter that had taken five years to be delivered. As he removed the contents, a piece of paper fluttered to the floor. Maurice retrieved it and read the message that was written in a crude English print:

April 4th, 1941

Dear Sir:

I am sorry but I can no longer send packages to your family in Belgium and Poland. Packages are not going through any more. Enclosed is the balance of money that went unused. It is for $40. Good luck!

Sincerely,

Arturo Cabral

Maurice took the $40 draft with him to work the next day, framed it in the afternoon and placed it on the wall of his office. He never spent that draft and he was daily reminded that in the midst of all the horrors that had taken place during the war, man’s humanity towards his fellow man had not completely vanished. It served equally as a reminder to him that he had been so fortunate during the war to have encountered many people, strangers, Jews and non-Jews alike, political and community leaders as well as everyday people whose acts of selflessness contributed to his survival and his lifelong belief in the ultimate goodness of mankind.

© 2014 Redmont Tales

By Joseph Rotenberg