(Credit: Joseph C. Kaplan)

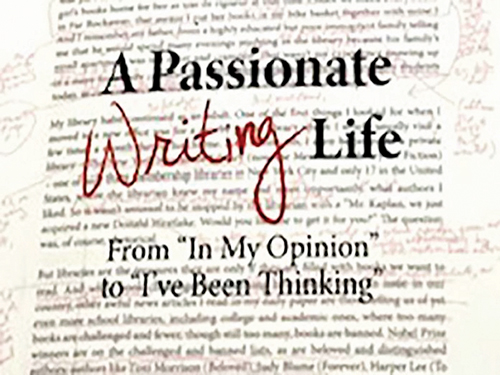

Reviewing: “A Passionate Writing Life,” by Joseph C. Kaplan. ISBN-13: 9798218962715

As a memoir lover, I was excited to have the opportunity to review “A Passionate Writing Life” by Joseph C. Kaplan. Traditional memoirs are written as a retrospective, the story of one’s life told with the benefit of hindsight and maturity, told by someone who has had years to reframe, rethink and re-polish their earlier experiences. This is not that memoir. Mr. Kaplan, a retired lawyer, has been a writer since his college days in Yeshiva University. His book is a compilation of the many articles he has written over the years, grouped by topic, and reprinted (for the most part) without being re-edited. Prefacing each article is a paragraph or two, or three, of new writing that links the articles together and creates a space for Mr. Kaplan to comment and reflect on his previous articles through the lens of time.

“I’m a Modern Orthodox Jew. And a feminist.” Without equivocation, the author introduces himself to the reader by sharing two of the most important issues that compel him to write, and indeed, roughly the first quarter of the book is dedicated to women in Judaism. One would think that this is the natural outgrowth of being the father of four daughters, but Mr. Kaplan asserts that this fact “does not define me, but it’s important in understanding who I am… I don’t believe it’s a main or direct cause of my feminism.” In an article penned in 1975, Mr. Kaplan describes the simchat bat ceremony he and his wife Sharon crafted to honor the birth of his first daughter, Micole. “As Orthodox Jews, we of course confined ourselves to work within the halachic tradition, but we felt certain that we could still prepare and perform a simchat bat in a manner that would be within the traditional framework while still giving expression to our own deeply felt emotions, thoughts, and desires.”

In describing the ceremony, Mr. Kaplan is careful to point out that it was not an adaptation of the traditional male ceremony because a mere adaptation would hinder the ability to innovate. In an article written 37 years later, he expresses disappointment that the simchat bat is not a more universal celebration amongst Orthodox Jews, but also comments that when he grew up there was absolutely no celebration marking either rite of passage for girls, neither birth nor bat mitzvah; he is hopeful that more changes will occur when his grandchildren’s generation reaches these milestones. Much of the book is laid out in this fashion; a topic is introduced and then explored by grouping together older and newer articles about said topic along with a discussion about how things have changed (or not changed) in the interim years.

Other topics discussed in this section are bat mitzvahs, women and prayer, Jewish divorce, and Torah education for women. One of my favorite observations comes from a 2017 article about a Modern Orthodox wedding that the author attended with his wife. To his surprise, there was a mechitza splitting the dance floor. Granted, it was a mechitza made of shimmering lights which did not physically prevent men and women from easily moving from one side to the other, but its sheer presence was puzzling to him because years ago a mechitza would not have been present at such a wedding. Mr. Kaplan then talks about the troubling trend of increasing gender separation and female gender exclusion in the frum community at large. “…[T]he result is that this growing extremism moves the fences for all groups. Thus Modern Orthodox mainstream positions have become more severe, since the center keeps moving right.” Spot on.

In January 2016, Rabbi Dr. Eugene Borowitz, a Reform theologian whom the author was close with, passed away. The two had known each other through a Jewish publication called Sh’ma magazine, which Mr. Kaplan had written for, and as is the way of all writers, Mr. Kaplan was moved to write about his friend. Thinking that an article written by a Modern Orthodox Jew about a Reform rabbi would be an interesting spin, he reached out to some well known Jewish publications who “gently, but firmly” declined his submission. Disappointed yet determined, he submitted his article to his local Jewish paper The Jewish Standard, and within hours the editor, Joanne Palmer, accepted his article. This submission prompted Ms. Palmer to offer Mr. Kaplan a column in her publication, and that column, titled “I’ve Been Thinking,” is the source material for many of the articles in this book.

When he asked Ms. Palmer what topics she wanted him to write about, she responded, “Whatever you like.” This undefined directive granted Mr. Kaplan the license to explore any topic that resonated with him. In this series of articles he uses his “distinctive life experiences as jumping off points to muse about non-page-one topics like kindness, friendship, or decision-making,” as well as discussing “Jewish topics of concern to my own particular community.” My personal favorites are his articles that discuss his family members, more specifically, his family members who are no longer of this earth. After his mother passed away, predeceased by his father, he ruminates after shiva “that in the past week we sat shiva not only for our mother, we sat shiva for both our parents, for our childhood, and for their home.”

What compels a writer to craft a memoir? One important reason is to preserve the family’s mesorah, their legacy. In a series of articles written in 2018, Mr. Kaplan regrets that he did not ask his parents and grandparents more about their lives. “I had numerous opportunities to ask, but I guess at the time I didn’t think it was important. I was busy being young and active. Now I know how so very important it was—but the opportunities are gone … You can’t pass down family history you don’t know.” Poignant and so relatable; how many of us have experienced this same regret, the regret of being unknowingly self-centered, of thinking that our parents would live forever and that we had forever to sit down with them and actually listen to what they had to say. Whether intentional or not, this memoir preserves Mr. Kaplan’s life story and the stories that came before him, a beautiful gift to his family but also a gift to his readers due to the universality of his observations and themes.

I really enjoyed this book. I enjoyed it even more after I read it a second time, when I was able to concentrate on the writing itself without having to concentrate on the story arc. Mr. Kaplan’s use of the English language is eloquent without being pretentious and his ideas are voiced in a manner that is opinionated without being overly preachy or didactic. Even when I didn’t agree with some of his ideas, I admired the systematic way in which he presented these ideas: logical and lawyerly, wildly passionate yet never mean or disparaging against those with differing opinions. Indeed one gets the sense through various anecdotes that he has great respect for those who practice Judaism in ways that are unlike his own, both to the left as well as to the right.

“I cannot, of course, expect that you, my readers, will feel that same connection to my writings, or will agree with all, or even many, of my opinions. I do hope, however, that you enjoyed taking this journey with me.”

Dr. Chani Miller is an optometrist and writer who lives in Highland Park, New Jersey, with her family.