In the event a couple is unable to settle their marital differences by themselves or with the assistance of a mediator, the IBD will address all marriage matters including the dividing up of marital assets, spousal and child support as well as parenting arrangements.

From time to time, there emerges the issue of igun—known in modern Hebrew as sarvanut get (get recalcitrance) where either the husband refuses to grant a get to his Jewish wife or the Jewish wife refuses to accept a get from her Jewish husband.

In a situation of a husband who refuses to give a get, some of our lines of inquiry are the following: Under what conditions may a beit din obligate a husband to give a get unconditionally? In the event of a husband’s continued refusal to give a get, what ammunition is in the halachic arsenal to address this phenomenon, a matter which our community has been grappling with for many years? Obviously, for those rabbinic authorities and communities who endorse the execution of a prenuptial agreement, a divorcing couple in these communities may find solace in the fact that generally the matter of igun (loosely translated—“the chained one”—the withholding of a get) will not rear its head. However, for the thousands of couples who have been married for decades without the execution of a prenuptial agreement and for those who continue to be married without availing themselves of this agreement either out of ignorance that such a panacea exists or due to the fact that their rabbinic decisors reject their implementation, what do we have in our halachic stockpile to wage a war against a husband’s refusal to give a get?

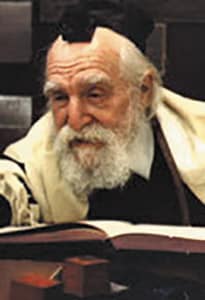

Rabbi Moshe FeinsteinMay a beit din direct the imposition of social and economic isolating measures introduced in 12th-century Ashkenaz known in halachic parlance as “harchakot of Rabbeinu Tam”? Must a beit din have grounds to obligate a get (“chiyuv le’garesh”) prior to invoking these measures or is it sufficient to render a ruling of advising or recommending a husband to give a get? Are there grounds to authorize a wife to litigate her monetary claims in civil court which may result in a husband’s willingness to give a get? Upon discovery that there were no eidim (witnesses) under the chupah during the time of kiddushin who heard the husband reciting “harei at mekudeshet li…” and witnessed the mesirah (the husband placing a ring on his prospective wife’s finger) or that an eid was ineligible to serve as a witness, may a ruling be handed down by a beit din which would be mevatel the kiddushin (loosely translated as “voiding the marriage”) and therefore a get would not be required? Under what conditions may the invalidation of a Torah-observant adult Jewish male eid kiddushin result in bitul kiddushin? If a husband intentionally or unintentionally fails to disclose to his prospective spouse prior to marriage that he had a “mum gadol” (a major flaw) such as being impotent, unwilling to have children, gay, being mentally dysfunctional or being a criminal, are there grounds and under what conditions can such a marriage be voided?If a husband intentionally or unintentionally fails to disclose to his prospective spouse prior to marriage that he had a “mum gadol” (a major flaw) such as being impotent, unwilling to have children, gay, being mentally dysfunctional or being a criminal, are there grounds and under what conditions can such a marriage be voided? In other words, under certain conditions our beit din may void a marriage not annul (“mafkia”) a marriage.

Clearly, there exist divergent halachic traditions which respond to all of the aforementioned questions. On the one hand, the kiddushin (betrothal) relationship establishes a personal status, namely, that of a mekudeshet, a woman designated for a particular man and prohibited to all others. The establishment of this personal status, known as ishut, renders both spouses subject to various prohibitions, e.g. sexual relations with various relatives become prohibited, as well as creating at the time of the marriage various financial duties for both the husband and the wife. Clearly, a beit din engaging in bitul kiddushin entails a readiness to nullify the issur of eishet ish, the prohibition of being a married woman. Whereas a refusal to invoke bitul kiddushin means that the issur continues to exist, the implementation of bitul means that the issur no longer exists and the wife, in the case of an agunah, is permitted to remarry without the issuance of a get. On the one hand, prohibiting bitul kiddushin in part is due to the lurking fear that the woman is an eishit ish and therefore, should we permit her to remarry and should she bear children, her offspring will be mamzerim. For those who sanction bitul kiddushin on the other hand, it is in part due to the fact that we want to prevent mamzerut lest the agunah remarry without halachic permission.

Given that the propriety of voiding a marriage entails entering into “the universe of issurim,” the issue of being stringent or lenient regarding such matters emerges. In 1909, a rabbinic controversy erupted concerning the question whether or not oil derived from sesame seeds are permitted on Pesach when the process of production prevented any possibility of leavening. Despite the opposition of various Yerushalmi rabbinic decisors, Rabbi Kook, then rabbi of Yaffo, certified as kosher the factory that was producing the sesame oil. Responding to the concern that such a ruling would create a small opening in the wall, resulting eventually in “a breach in the wall of halacha,” Rabbi Kook writes as follows in his Teshuvot Orah Mishpat, Orah Hayyim 112:

And most importantly, I have previously written to these esteemed Torah scholars that I am aware of the character of our contemporaries. It is precisely by observing that we are ready to permit based upon plumbing the depths of halacha, they will arrive at the understanding that we are allowing it because of the truth of the Torah, and many will come, with God’s help, to listening to the voice of the instructors of Torah. But if it is discovered that there are such matters that from the perspective of halacha ought to be permitted and the rabbis are insensitive to their burdens and pain of Israel and allowed the matters as prohibited, this will result, God forbid, in the desecration of God’s name. Many of the transgressors of halacha will say regarding basic rules of Torah that if the rabbis wanted to permit them they could have done so, and the result will be that the halacha has been perverted.

To state it differently, in Rabbi Kook’s mind, “the slippery slope” is a risk associated not only with lenient judgments but equally with unnecessarily stringent rulings which may result in “the breach of the wall.”

Regarding “the breach of the wall,” quite instructive and incisive are the words of Rabbi Meir Gavison, a contemporary of Rabbi Yosef Caro, the author of our Shulchan Aruch:[1]

The Scholars were…especially attuned to the imminent transgressions of halacha, and the licentiousness which may emerge as a result of the wife’s status as an agunah. For if permission for her to remarry is withheld, people will intentionally violate…Possibly they will be unable to subdue their instincts and will surrender to temptation should we fail to identify a way of permitting them to remarry…. And consequently, it is therefore our responsibility to inquire for grounds on their behalf, and… to allow her in order to preempt any possibility of violation. And it is no minor issue to commit a sin and to cause others to sin…

Over sixty years ago, Rabbi Yitzchak Z. Kahana has well-documented in his classical work, Sefer ha-Agunot, the numerous teshuvot which address the acute need to offer solutions to deal with the woman whose husband has disappeared (“the classical agunah”) lest she remain an eishit ish, as well as notes the well-trodden mesorah to rely on lenient opinions in a matter of agunah.[2] A marriage which has no prospects for “shalom bayit”—marital reconciliation—and therefore is “dead,” yet the wife cannot receive the desired get in order to rebuild her life, is deemed an igun matter and is deserving of the same halachic consideration of seeking leniency accorded to the classical igun while simultaneously preserving her halachic-moral persona as a bat Yisrael, a daughter in our community. As Rabbi Eliyahu Alfandri notes in his Teshuvot Seder Eliyahu 13, get recalcitrance entails “withholding good from our friends” and as such is an infraction of “loving your neighbor like yourself” and “failing to rescue your fellow Jew.”

Upon identifying a solution we ought to heed the words of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, who states”[3]

“And it is a major prohibition “le’a’gain” (“to leave a wife in chains”) if one has the ability to address the situation and does not resolve it.”

Lest one be concerned about the view of other rabbis who look askance at voiding marriages, Rabbi Feinstein observes in his Dibrot Moshe, Ketubot, vol. 1, pages 244-245:

Those who are of the opinion to prohibit are well aware the basis for permitting the matter and they should not be surprised when they hear that there are others who allow it. And if they fail to understand the grounds for permitting they are not mor’eih hora’ah (loosely translated as authorized arbiters in matters of prohibitions-AYW), and one should not be apprehensive of them at all and they must inquire into the matter and they will see the side of permitting the concern and they will no longer be surprised.

Lest one contend that seeking solutions to matters of “igun” is to be relegated to Torah luminaries such as Rabbis Naftali T. Berlin, Elchanan Spektor and Yosef Baer Soloveitchik, author of Beit ha-Levi, following in the footsteps of dozens of authorities, battei din and rabbis here and in Eretz Yisrael have under certain conditions voided marriages.

Despite the fact that many of these dayanim are surely neither very well-known nor as well-respected as nineteenth century Torah giants Rabbi Berlin, Rabbi Spektor and Rabbi Soloveitchik they did not shirk from their responsibility to address such weighty issues. As Rabbi Yitzhak ben Dovid of nineteenth century Kushta writes in his Teshuvot Divrei Emet 9 (beginning):

If every Torah scholar would refrain from responding and say, “How can I enter this flame of a mighty blaze due to the severity of the prohibition of incest (“erva”)?”…Every Torah scholar, one of minor stature like one of major stature, is obligated to seek with candles—a careful search in holes and cracks—possibly he will find relief for the benefit of the daughters of Israel to save them from igun…

Just as a posek must perform his due diligence to search for a solution, similarly, an agunah must persist in identifying a beit din who may afford her relief. Even if an agunah received a reply from a beit din or a rabbi that halacha affords no solution for her igun, nonetheless, many authorities permit her to revisit her case by another beit din or rabbi. Lest one challenge this conclusion based upon the Talmudic rule regarding issurim, “If a scholar prohibited something, his colleague has no authority to permit it after it already has been forbidden,”[4] this rule may either be inapplicable in contemporary times[5] or “the matter of agunah” is an exception to the rule.[6] An agunah being forced to remain alone, albeit married, is untenable and therefore she should continue to seek out rabbinic authorities who hopefully address her situation.

For further information about the IBD as well as access to numerous rulings of poskim who in the past have voided marriages, a recent decision of a Haifa Beit Din and access to some of the decisions of the IBD, please proceed to www.internationalbeitdin.org.

[1] [1] Teshuvot Maharam Gavison 82. See also, Iggerot Moshe EH 1:43.

[2] [2] Y. Z. Kahana, Sefer ha-Agunot, Jerusalem 5714, 7-76.

[3] [3] Iggerot Moshe EH 1:117.

[4] [4] Berachot 63b; Avoda Zara 7a.

[5] [5] Aruch ha-Shulchan Yoreh Deah 242:63; Teshuvot Maharsham 9:79

[6] [6] Teshuvot Sha’arei De’ah 100, Teshuvot Milluei Even 29(end); Teshuvot Heichal Yitzchak EH 2:45.

By Rabbi A. Yehuda Warburg, Director, International Beit Din