Before I knew of the Rokeah, I met his wife.[1]

My eleventh-grade medieval Jewish history teacher, Raizi Chechik, introduced us to her with a photocopied handout of the elegy R. Eleazar of Worms composed after the murder of his beloved wife Dolce.

A valorous wife, crown of her husband, daughter of princes – A God-fearing woman praised for her good deeds.[2]

R. Eleazar of Worms, the illustrious medieval rabbi known by the name of his legal work Sefer Rokeah, introduces the elegy, composed as a poem, by recounting the events that led to the death of his wife and their two daughters, Bellette and Chana. The attack occurred on an otherwise ordinary evening in November 1196. In the introduction, R. Eleazar describes sitting at his table, having just reviewed that week’s Torah portion of Vayeishev and reflecting on a rare moment of stillness in Jacob’s life.

And he sat in security.

In his ever-precise wording, the Rokeah alludes to the rabbinic teaching that the verb to sit or settle found in the Torah highlights Jacob’s desire to settle in peace, after years of exile, fraught encounters, and the tragic death of his beloved Rachel. He hoped to finally find serenity, but instead Jacob’s sorrow was compounded by the loss of the only remnant of that relationship, Joseph.[3]

On the evening of the twenty-second of Kislev, R. Eleazar recounts, his own serenity was interrupted when two Christian intruders entered their home and began attacking the inhabitants. They struck men and boys alike, but only the couple’s two daughters, ages six and thirteen, succumbed to their injuries. Amidst the chaos, his wounded wife Dolce burst forth from the house into the cold night and began to cry out for help. Her screams lured the attackers out of the home and into the street, where they murdered her.

And the righteous woman collapsed and died.

Dolce’s heroic diversion enabled her husband to secure the door and protect the home’s inhabitants.

Until help arrived from above.

R. Eleazar’s subsequent demands for justice on behalf of his murdered wife led the authorities to capture and kill her attacker within a week of the incident.

And I was left bereft of everything with pain and tremendous suffering.

A prolific writer of piyyut, a heartbroken R. Eleazar channeled his faith-filled grief and composed elegies for his wife and each of his daughters. Yet the elegy for Dolce of Worms does not dwell on her death—it fittingly intersperses the verses of Eshet Hayil[4] to memorialize her life and deeds.

Her husband’s heart relied on her. She fed and clothed him with honor, to sit with the elders of the land, to bestow Torah and good deeds.

As R. Eleazar carefully chronicles, Dolce’s kindness and contributions extended into her home, synagogue, and broader community.

At home, Dolce spent much of her time cooking, spinning, and sewing. She fed and clothed the family members, as well as the yeshiva students who lived with them. She mended their clothes and used her spinning skills to prepare materials to bind new books and repair old books in the synagogue and beit midrash, where she also prepared wicks and took care of the lighting. R. Eleazar credits his wife with preparing forty sifrei Torah, as well as materials for tefillin, megillot and other holy books. Within the larger community, Dolce is remembered by R. Eleazar as generously providing for the poor, visiting the sick, beautifying brides for their wedding days, and ritually bathing the dead and preparing their shrouds for burial. She did all this while financially supporting her husband so he could pursue his studies and lead the community. Her earnings also covered the cost of the food and milk for the yeshiva students who lived with them, as well as the salaries of the teachers. Thus, Dolce truly embodied the descriptor of Eishet Hayil, a term which implies fiscal resourcefulness. Interwoven among these achievements, R. Eleazar continuously describes Dolce as cooking for the family, for the students, sometimes meat, sometimes buying milk, or preparing the table for Shabbat or festive holidays.

She was a loving mother who encouraged the education and Torah study of her children. Dolce prayed twice a day, and R. Eleazar cites specific passages she recited daily, such as Nishmat and the Aseret ha–Dibrot. He credits her with the piety of their two daughters and teaching them to recite the Shema. She was a presence in the synagogue, the first one there and the last to leave. She could be seen standing all day Yom Kippur in prayer. She taught and led other women in prayer, sang zemirot and listened intently to her husband’s derashah each Shabbat. She recited psalms and supplications. She spoke with wisdom and was perceptive. She knew all the halakhot of kashrut, what is permitted and forbidden. Among the accolades R. Eleazar applies to Dolce are serving God with awe, love, joy, modesty, piety and alacrity.

R. Eleazar characteristically composed the elegy as an acrostic of his name along the inner column, which spells, “Eleazar the little, the miserable, and the needy.” He concludes:

She was happy to do the will of her husband and never once angered him. May God remember her pleasant deeds. May her soul be pleasured, bound to the binds of eternal life, grant her the fruits of her labor in Gan Eden.

To our knowledge, R. Eleazar never remarried.

There are encounters with teachers and texts that can change your life. For those studying the past, this text is very useful. It is rare for a medieval text to focus solely on the efforts and experiences of a Jewish woman. For that reason, it is widely cited in works that touch on Jewish life in the Middle Ages, whether in discussions of economics (as Dolce may have been a moneylender), synagogue practice (she attended regularly and led the women in prayer), household duties (sewing, spinning, cooking, etc.), typical number of children (they had three), the relationships between Jewish spouses (mutual respect and cooperation is expressed throughout the text), or even the question of Jewish names (Dolce and Bellette had vernacular names). But for me, as a teenage girl, the Rokeah’s elegy offered a glimpse into the past and prism for my present—and little did I know then, my future too.

Jewish girls have many female role models in Tanakh. There are fewer in the Talmud, but still notable. The list grows shorter as one progresses into the period of the Rishonim. Over the course of my Jewish education, I learned much about Rashi, Rambam, and other great rabbis across Ashkenaz and Sefarad. I could aspire to their erudition and middot, but I could not emulate their wives: about them, history is mainly silent. The Rokeah’s writing is a rare gift, a glimpse into a Jewish home with Dolce going about her daily activities, sometimes mundane, but always impactful. I kept the photocopy of that elegy long after the school year ended. Its description of the wide-ranging spiritual, domestic, and communal engagements of Dolce of Worms became my bucket-list of Jewish womanhood. And I have grown with the text.

As a high school student, I was moved by the praise of Dolce’s intellect, her knowledge of halakhah, her synagogue attendance and disciplined prayer regimen. I was drawn to learning Torah, careful about shul attendance, and was inspired by the image of a woman so learned for her time. In college, I taught the text at a Torah learning camp in Israel, to women younger than I, but equal in their eagerness to learn. That fall, Raizi Chechik made another life-changing introduction; this time it was to the man I married.

I entered my marriage with few domestic skills (albeit with a drive to gain some) and a steadfastness to continue to strive in Torah. I had once heard it said that most women’s Torah education peaks in high school; I decided that would not be me. With my husband’s encouragement, I was blessed to continue to study and teach Torah as our family grew. And although my teenage self would never believe it, I have come to value the descriptions of Dolce’s constant cooking, mending, and providing. I am moved by her quiet, private acts of kindness. I relate to her busyness. I respect her concern for both the physical and spiritual well-being of others. I marvel at her shul attendance and communal outreach on top of family and career. I aspire to achieve Dolce’s domestic prowess, while wading into the study-centered realm of the Rokeah.

Four years ago, I left my teaching position to work full-time on completing my PhD dissertation, “The Interconnectivity of the Written and Oral Torah in the Thought of R. Eleazar of Worms.” By “full-time,” I mean the hours between the morning school drop-off and the afternoon pickup. During those coveted quiet hours, I sat secluded at home or in the university delving into R. Eleazar’s writings, which span halakhah, mysticism, biblical and midrashic exegesis and piyyut, trying to trace and systematize the web of biblical and rabbinic sources and numerical calculations he wove together in his writings. Surrounded by piles of sefarim and academic works in carefully constructed piles, along with twelve search engine tabs and digitized manuscripts open on my computer screen, on a scavenger hunt all in the service of one footnote… It was bliss. Breathing in the scent of old books mingled with freshly printed peer-reviewed articles, I would think, “What a dream!” but also, “What am I making for dinner?” By mid-afternoon, as babysitters and school children were readying to release, my focus would necessarily shift from the intellectual Torah world of the Rokeah to the domestic and communal realm of his wife Dolce.

I am a student of both R. Eleazar of Worms and his wife Dolce; attempting to exist in both their realms is a challenge seemingly unique to our time.

I recall a rainy Friday night, years ago, when my husband and I left some sleeping children and a very awake 3-week-old baby at home with our Shabbos guests, so I could teach R. Eleazar’s elegy for Dolce at a Friday night oneg. I had committed to speaking there well before the baby was born. Afterwards, an older rabbi whose wife had passed away approached me visibly moved and thanked me for bringing this text to his attention. “How unusual to have a gadol be-yisrael describing his wife this way!” he exclaimed. The oneg portion of the evening began, and a younger woman came over to ask my advice about advanced Torah learning opportunities for women. We spoke for a bit, but my baby weighed on my mind. It had been difficult to get out of the house that night, and I remember feeling both gratified to have done it, but desperate to get home to feed my baby. I could not indulge in rugelach and scholarly schmoozing.

When I teach R. Eleazar’s elegy, audiences sometimes ask, “Could one woman really have done all this? All that cooking!?” Setting aside discussions of how much longer domestic tasks took in the Middle Ages, for me the comment–the skepticism–is never fully about Dolce. It is about the many women today whose wide-ranging activities are overlooked. The women who shop and cook for their families; outfit them; pack school lunches and snacks (nutritious and ever adapting to each household member’s preferences); women who try to learn, attend, or give shiurim, who study halakhah and teach kallot, who are involved with the Hevrah Kaddishah, the Bikur Holim, the youth, education, or other shul committees; women who are active in communal organizations; women who cook regularly for their own families, but also for the new mom, the new neighbor, or those struggling, not to mention lavish multi-course meals every Shabbat and Yom Tov (now featuring homemade dips!), all while working outside the home to help support their families. How many women do you know like that? I know more than I can count. Their weekly schedules would also sound unbelievable if listed in the same way as in the elegy for Dolce.

Still, I think Dolce would be the first to reassure me that it can be done.

I recall fondly how Dr. Arthur Hyman z”l, a former dean of the Bernard Revel Graduate School, encouraged me to pursue a PhD while I rocked my eldest in a baby stroller in his office. It is possible to do both, he assured me. Some of his best scholarship was done while he was awake with his baby son in the middle of the night, he reminisced. “Don’t cook so much,” he advised with a smile. The men in my life, from family to professors, encouraged me throughout my graduate studies and as my family grew. Dolce supported her husband so he could study, and my husband supported me.

We are blessed to live in an age where women have more opportunities than ever to learn and teach Torah. I enthusiastically and humbly embrace this opportunity. I have come to appreciate, though, that attempting to enter the realm of R. Eleazar means learning in addition to and not instead of. As Dolce demonstrated, hesed must not be left behind. It is not a relic of the past that we feed the hungry and clothe the naked. It is how we imitate Hashem and become godly. It is our heritage as Jewish women, though hesed is by no means afforded only to women. And if I am absolutely honest, at the end of the day, my regrets are not that I didn’t learn or write more, but that I didn’t make that extra meal for someone who needed it, or was too busy running between work and home to visit the homebound, pay a shivah call, or volunteer for the school’s Purim carnival. Likewise, the expectations of men’s involvement at home have also changed, and maybe some of my male colleagues, who seem to sit tranquilly in the library or beit midrash, also feel pulled between priorities, but for me the dichotomy is especially stark as an einah metzuvah ve-osah.

In practical terms, attempting to exist in the two realms of Jewish scholarship and stewardship means preparing for Shabbat and Yom Tov by shopping, cooking, cleaning, and researching for shiurim to be delivered. It means preparing to welcome a new baby by organizing shelves as well as sources for the derashah about the baby’s name. It means missing once beloved communal prayers and learning opportunities to nurture little ones at home and ambivalently leaving them behind to appreciatively study or teach outside the home.

While Dolce’s activities can be categorized into the different realms of domestic, religious, and communal efforts, R. Eleazar doesn’t list them separately. Rather, he presents them as interwoven. In the same stanza, Dolce is involved with ritual objects and cooking. She is sewing and sharing her wise counsel. Buying milk for the student boarders is juxtaposed with praising her keen intellect. This is the perfect representation of many Jewish women today in many fields, including Torah studies. To update the description, with the advent of cell phones and online shopping, we are multi-tasking more than ever, cooking while we counsel, learning while rocking the stroller with our foot, and ordering the milk (or groceries) online all at the same time. I write this not as self-aggrandizement, but to highlight the quiet valorous juggling act of the many Dolces of today, and to inspire the Dolces of tomorrow.

There is one domestic activity that manages to evade the elegy for Dolce: laundry.

The night before my doctoral oral exams, I decided to wash eight (!) loads of laundry that had piled up during my intensive studying period.

That was being Dolce.

The next morning, nine months pregnant, I sat for a farher with three learned scholars who questioned me on the contents of a reading list twelve pages long that had taken me over a year to study.

That was the world of R. Eleazar.

I passed, but the sense of accomplishment was not able to settle. It was a Friday and I had to rush home.

After I picked up my kids, I allowed my mind to mull over my committee’s questions and my responses. But when my youngest children took my hands to cross the street, my thoughts immediately shifted to “What am I making for Shabbos?”

She girded herself with strength and stitched together some forty Torah scrolls. She prepared meat for special feasts and set her table for the whole community.[5]

[1] Special thanks to Stu Halpern and Abe Socher under whose encouragement this essay was born as part of the Straus Center Mentorship Program at Yeshiva University and the helpful feedback from members of the 2019-2020 mentorship cohort and Shaina Trapedo.

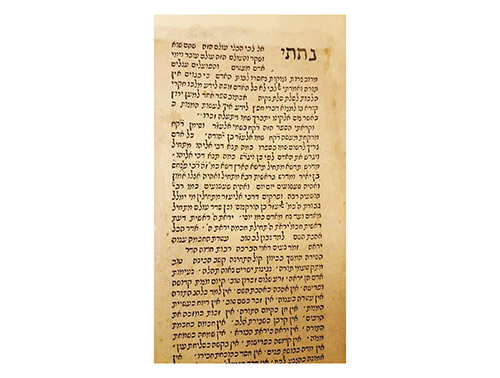

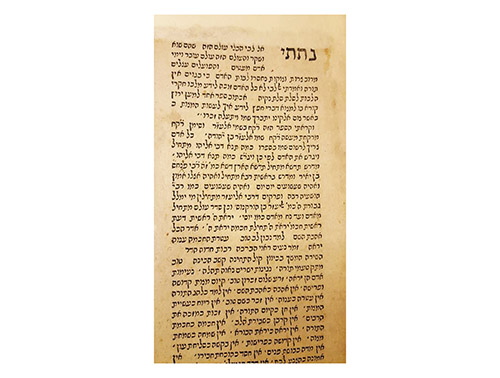

[2] For background and the original Hebrew text, see Sefer ha-Rokeah [ha-Gadol] (Jerusalem: Zichron Aharon, 2014), 4-6. Translations are my own unless otherwise noted.

[3] Bereshit Rabbah, parashah 4.

[4] Proverbs 31: 10-31.

[5] Translation from Judith Baskin, “Dolce of Worms: The Lives and Deaths of an Exemplary Medieval Jewish Woman and her Daughters,” in Judaism in Practice, ed. Lawrence Fine (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2001), 435.

By Chaya Sima Koenigsberg/The Lehrhaus

(Printed with permission)