In recent years, too many in the African-American community have expressed a disconnect to Holocaust topics, seeing the genocide of Jews as someone else’s nightmare. After all, African Americans are still struggling to achieve general recognition of the barbarity of the Middle Passage, the inhumanity of slavery, the oppression of Jim Crow, and the battle for modern civil rights. For many in that community, the murder of six million Jews and millions of other Europeans happened to other minorities in a faraway place where they had no involvement.

However, a deeper look shows that proto-Nazi ideology before the Third Reich, the wide net of Nazi-era policy and Hitler’s post-war legacy deeply impacted Africans, Afro-Germans and African Americans throughout the 20th century. America’s black community has a mighty stake in this topic.

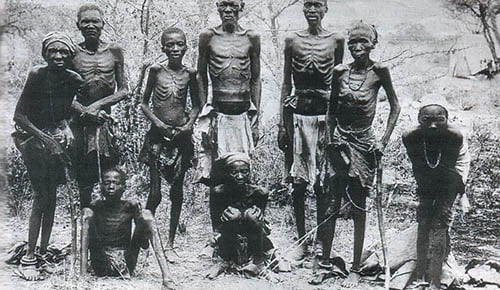

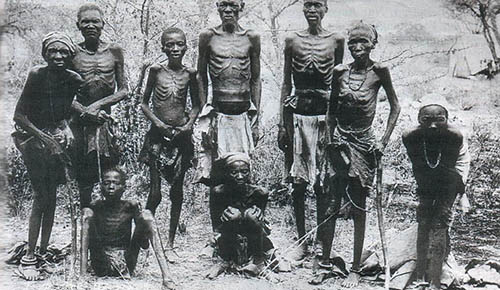

It all begins with the oft-overlooked first genocide of the 20th century, Germany’s deliberate extermination in 1904 of the Herero and Nama tribespeople in colonial Southwest Africa, now known as Namibia. The atrocities included explicit extermination orders, mass shootings, bonfires immolating wounded or starving Africans, the wearing of identification numbers and organized transport in cattle cars to concentration camps. One of these camps, Shark Island, was considered a “death by labor” camp. In its campaign against the Africans, the German authorities introduced several words and concepts: Konzentrationslager or concentration camp, untermenschen or subhumans, Mischlinge or mixed race and anti-race mixing laws.

Many veterans of Germany’s South-West Africa extermination campaign went on to become key Nazi activists or otherwise inspired major figures in the Third Reich. For example, Hermann Goering idolized his father, Heinrich, for his role as governor of South-West Africa. Goering’s 1939 official Nazi biography records reveal that the young Goering “was even more thrilled by his [father’s] accounts of his pioneer work as Reichskommissar for South-West Africa … and his fights with the Herero.” In the 1920’s, former colonial Trooper Franz Ritter von Epp went on to hire Adolf Hitler, fund the purchase of the Nazi newspaper Völkische Beobachter, and, with Ernst Röhm, helped found the Storm Troopers. The Storm Troopers even adopted the desert sand–colored brown shirt uniforms worn by the troops deployed in Africa.

After the Treaty of Versailles stripped Germany of its African colonies, German citizens were shocked to see African soldiers patrolling their streets. It is not widely known that when France occupied post-Great War Germany, it deployed 20,000 to 40,000 colonial African troops. The Germans reacted with a bitter national protest movement, imbued with sexual imagery, called “Black Shame on the Rhine.” When a generation of Afro-Germans arose, denigrated by Hitler and the Nazis as “Rhineland Bastards,” they were among the first to be forcibly sterilized.

When the Nazis came to power, like throngs of other loyal Germans, some Afro-Germans tried to join the Nazi Party. Hans Massaquoi, son of a Liberian diplomat and a German woman, was among those who wanted to sign up with his local branch of the Hitler Youth, just like the rest of his schoolmates. Young Hans was astonished to discover that the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, defining German blood and racial status, applied to him—denying him admittance. From that moment on, Massaquoi learned to live with the fear that the Gestapo would knock on his door. After the war, Massaquoi was able to emigrate to the United States, where he took a job at Ebony Magazine, rising to become the managing editor.

Ironically, African Americans were impacted beneficially by Nazi policy again in the ’30s when refugee Jewish professors, ousted from their posts in Germany, immigrated to the United States. Some 50 such refugees accepted teaching positions in historically black colleges and universities, helping to mentor the generation that fought the civil rights struggle. Among the students who credit the inspiration of German-Jewish professors is Joyce Ladner, who went on to organize civil rights protests with Medgar Evers and who would later rise to the leadership of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [SNCC] and the Congress on Racial Equality [CORE].

In the ’40s, when African-American soldiers were deployed to Europe, Nazi soldiers who encountered them treated them mercilessly, often committing massacres and war crimes against POWs.

After the fall of Berlin, returning African-American soldiers discovered Nazi racial policy was in force in some 27 US states that had adopted forced-sterilization laws based on corrupt German eugenic pseudoscience. Ironically, this race science had been nurtured in America first and then transplanted to Germany. In American state after state, eugenic boards quoted Nazi race theory and statutes as justification to sterilize blacks, and even confine them in camps as a social protective measure. In Connecticut, one state program even sought to implement Nazi-style race-based expulsions and organized euthanasia of those deemed unworthy of life.

We have only begun to chart the impact of German policy on those of African descent. More would be known, but such research remains almost completely unfunded and indeed unsupported. However, this much is certain: All misery bleeds the same color blood. Any man’s persecution should inspire every man’s crusade.

Human rights writer Edwin Black is the New York Times bestselling author of IBM and the Holocaust, War Against the Weak, and The Farhud. He can be found at www.edwinblack.com.

By Edwin Black