It was the fall of 1970, and I was living in Manchester, England. A few months earlier, Paul McCartney’s “The Long and Winding Road” was first released.

The long and winding road

That leads to your door

Will never disappear…

The wild and windy night

That the rain washed away

Has left a pool of tears

Crying for the day…

(© Sony/ATV Music)

It was also the fall of 1970 when meetings with my newfound cousin Samuel, of West London, first revealed the Holocaust thread that wove its way through my father’s family. No family member had ever discussed this, nor had they mentioned that at least 225 of my grandparents’ relatives in Galicia had perished. It wasn’t until 1967 that we even knew of Samuel’s existence. Until then, California was the outer fringes of our bloodline’s existence. Years later, during my father’s interview for the Museum of the Jewish Heritage’s “In Their Own Words: Jewish Veterans of World War II” project, he first revealed the extent of my paternal family’s destruction.

My paternal relatives mostly lived in shtetls in or around Lvov, a thriving Polish city prior to World War II. My grandmother was from Tartakow and my grandfather from Sokal. At the time that they departed as newlyweds for America, Lvov was Lemberg, part of Emperor Franz-Josef’s Austro-Hungarian Empire. When my grandparents came to this country, I was told, they shut the door behind them, and never looked back. They cared for the landsmener who followed them to America. Unfortunately, they died long before they could have helped those left in Lvov and even longer before I was born and could have inquired about any of this.

Samuel re-opened the door my grandparents shut. His own profoundly moving Lvov-to- England Holocaust survival story is for another time, but his door to the past segued to another “pool of tears” and a bittersweet “long and winding road,” for those whose escaped from the Nazis via the sewers of Lvov.

Ukrainian archeologists recently conducted a dig that confirmed the sewer hideout’s location and artifacts used there. (Liphshiz/JTA, The Jerusalem Post, 10/27/21). Yet this find is most meaningful when it is contextualized within the story of those who languished but survived the sewers’ depths and those who perished. Thanks to Samuel, the sewers saga triggered a succession of interlinked, personal recollections.

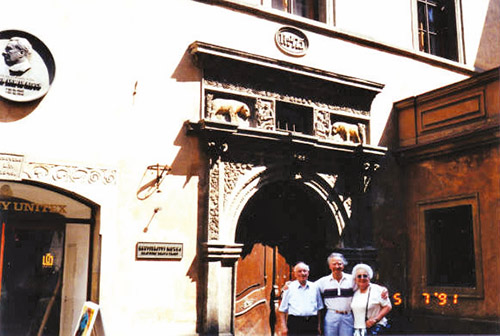

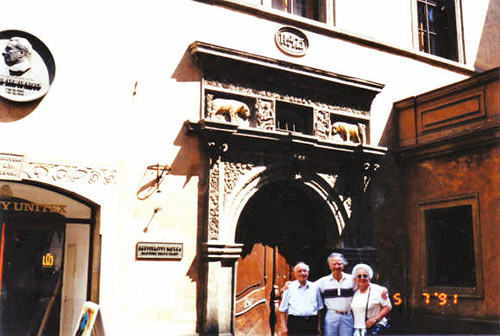

The smiling photos taken in Lvov, where Samuel finally returned with his friends Mundek and Klara Margulies and their son Henry, belie both families’ tragedies and the life-affirming strengths they summoned. Only after three-plus decades of knowing Samuel did he share skeletal details of the Margulies’ 14 months in Lvov’s rat-infested sewers and only after a fortuitous internship and London encounters with a BBC writer/director and the Margulies family did I learn the full saga.

Samuel had told me about “A Light in the Dark,” Robert Marshall’s 1989 BBC Timewatch documentary. It chronicled the wartime survival of Samuel’s “landndsmener,” Mundek and Klara, and those who hid with them in the sewers. I hit a technology roadblock vis-à-vis the film but by 1993, as an intern at Discovery Channel, I managed to have a colleague secure a properly formatted copy of it from Discovery’s recently acquired BBC’s documentary archive.

That summer, while in London conducting preliminary graduate research, I met with Mr. Marshall, who had recently started his own company, Mars Productions. In between the release of Light in the Dark and our meeting, he had published “In the Sewers of Lvov,” a complete account of how Mundek, Klara and those with them had survived. We met again in 1995.

Although the outcome of the Margulies’ story was unlike that of my own family in Lvov, they both shared the common thread of Lvov Jewry’s destruction, in scope and chronology (See https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/lvov). In September 1939, 200,000 Jews lived in Lvov, which was under Soviet control. Thousands were refugees from the Germans’ invasion of Poland in September 1939. Shortly after Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941 and occupied Lvov, Ukrainian nationalists, egged on by the Germans, began to decimate the city’s Jewish population. Most of Lvov’s Jews, if not murdered within the larger city parameters, the ghetto in the north of the city, which the Germans set up in November 1942, or nearby, were sent to the death camp Belzec or the labor camp, Janowska. Prior to the ghetto’s liquidation, and seeking refuge from the Nazis and the Ukrainian militias, hundreds of Jews entered the sewers. Many died in the waters below and others could not tolerate the conditions. These Jews exited the sewers only to be killed. Some who remained were also discovered and killed by the Nazis.

It wasn’t until late 2011 that wider audiences became aware of the survivors in the sewers, when Marshall’s screenplay “In Darkness,” directed by Agnieszka Holland, was first released. The film garnered international attention and was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the 2012 Academy Awards. (Ms. Holland, the acclaimed Polish director of “Europa, Europa,” had paternal Jewish grandparents who died in a ghetto during the Shoah).

During the years that Mundek and Klara, along with eight other souls, including the Chigers and their children, Krystyna and Pawelek, found refuge and survived in the depths of the Lvov sewer system, they were aided by Leopold Socha, a Polish Catholic sewer inspector who initially hid them for money but continued to bring them rations when the money ran out. There were two other workers, Wroblewski and Kowalow, who assisted those hiding, but the film focused primarily on Socha, a reformed petty thief-cum-devout Catholic. Whether his motivations were always altruistic is not relevant, as he took the moral high road. Recognition by Yad Vashem of his heroism came posthumously. Socha died in a bicycle accident not long after the war (See https://lia.lvivcenter.org/en/storymaps/chiger/)

Although In Darkness was available as a DVD, it was R-rated and so, I thought, inappropriate for screening in my synagogue’s annual Kristallnacht commemoration. Instead, I substituted Light in the Dark for the program. Nevertheless, In Darkness excels artistically and as a largely accurate, although it is a minimally “commercially enhanced,” historical narrative.

In summer 2012, I again visited the U.K. Samuel, as well as Mundek and Klara Margulies, were no longer alive, but I located Henry Margulies, Mundek’s son, in London. Henry had emailed me the pictures of his parents with Samuel from their trip to their hometown, by which time Lvov had become Lviv. Henry, his wife Deanna, and I met that summer in London. He disclosed the “backstory” of life in the sewers and its aftermath, which I have supplemented with video interviews of him.

Klara, Mundek, and the others emerged from the sewers when the Soviet army liberated Lvov on July 25, 1944. Klara was expecting Henry. The Soviets permitted Polish-speaking survivors to return to Poland, where the family briefly lived before traveling to England. Klara’s surviving uncle resided there, and they waited there for visas to the U.S. Then Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld (of the Kindertransport) sent the Margulies’ to Ireland to work with refugee boys. Their daughter Cecilia was born there, but they returned to England several years later. Mundek cooked in yeshivot; the family went on to open a Kosher catering business (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JU6J1Kb6HR).

Henry kept the business going after Mundek and Klara passed. Both children married; Cecilia moved to the U.S. and Henry remained in London. At a gala screening for In Darkness, Henry was asked what he learned from his parents, which was to help as many people as possible and to listen to people “The main thing my parents taught me,” he said, “was to have respect for another person” (Getty Images). He is now retired; he had gone back to Lvov not only with his parents but also with the Hampstead Garden Suburb Synagogue in North London, which was “twinned” with and helped support the Lvov Jewish community.

The other eight survivors settled in various countries, including Israel, Germany and France. Krystyna Chiger, together with her brother Pawelek (he died in an accident at 39), moved to Israel with her parents. She trained as a dentist there, married another survivor, and then relocated to the U.S., where she practiced dentistry. Now retired and residing in Long Island, she is the last living survivor. Her memoir, “The Girl in the Green Sweater: A Life in Holocaust’s Shadow,” was published in 2008.

So although

The long and winding road

That leads to your door

Will never disappear…

The wild and windy night

That the rain washed away

Has left a pool of tears

Crying for the day…

The day has ultimately prevailed.

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at [email protected].