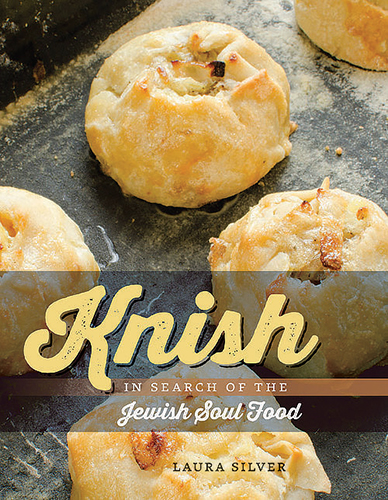

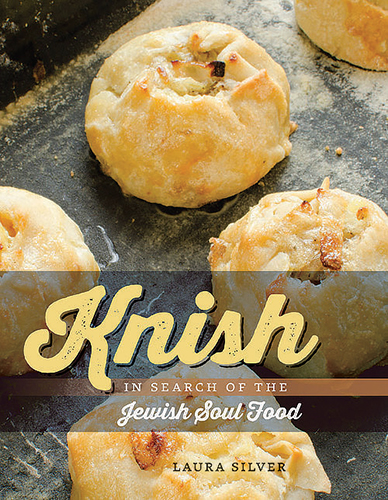

The history of the knish represents more than just the lineage of a fried, dumpling-like food. It demonstrates the often-central role of food in communities and cultural legacies. Laura Silver knows that all too well. She has consumed knishes on three different continents, and her exhaustive research on the iconic potato treat has resulted in her new book, Knish: In Search of the Jewish Soul Food, which was released in early May.

When she started her knish book project, Silver had no plans for an intercontinental journey, though she did plan to go to Vineland, N.J., home of the Pasta Factory, the company that purchased the famous knish recipes of Mrs. Stahl’s bakery. As a young girl from the New York borough of Queens, Silver vividly remembers heading to Mrs. Stahl’s in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn for knishes.

“Mrs. Stahl’s was our go-to place, but there were certainly knishes in other places,” she said. “When I grew up in Queens there were many Jewish delis around. Mrs. Fanny Stahl was born with the Yiddish name of Feige. She was an immigrant who supported her five children by doing many jobs, including cooking. She started the knish shop and ran it until her death. She was very active in the Brooklyn chapter of Hadassah (the women’s Zionist organization) and she knitted sweaters for the people of Palestine before Israel was a state. She was an entrepreneur par excellence. She worked very hard.”

Silver is considered the world’s foremost expert on the knish. But can she definitively say where the first knish came from?

“I don’t think it’s possible to know exactly who made the first knish,” she said. “It certainly happened in a different time but it was before 1614, the first recorded history of the knish, which is in a poem in the Polish language. It comes from a town called Krakowiec, which is in modern-day Ukraine in what would be the Pale of Settlement.”

The knish undoubtedly has links to the Polish town of Knyszyn, where Silver’s own family originated, she said. But before setting out on her quest, she had no idea that she might be related to direct descendants of the knish’s pioneers from that very town.

“I didn’t realize I was on a quest until I was in Poland with my family and we learned that our great aunt was from Knyszyn,” she said. “That’s what tipped me off that I might be a direct descendant of the knish, which I am in fact. It was bashert (meant to be).”

According to David Sax, author of Save the Deli: In Search of Perfect Pastrami, Crusty Rye, and the Heart of Jewish Delicatessen, Silver’s knish book is a lovingly researched volume that elevates the knish—arguably the humblest of Jewish foods—into a weighty symbol of history, identity, and family.

“Knishes haven’t met anything this good for them since the invention of mustard,” said Sax referring to Silver’s book. “The knish is ripe for the spotlight Laura has shone upon it. Just look at the lineup for Black Seed, the new Montreal bagel place in New York, and you’ll see that the revived interest in Jewish soul food is only growing. I bet we’ll see some amazing knishes in the years to come.”

Arthur Schwartz, author of Arthur Schwartz’s Jewish Home Cooking: Yiddish Recipes Revisited, said that the knish “has never been put to better use” than it is in Silver’s book.

“Laura Silver’s at-times poetic meditation on knishes is not only a cultural history of this filled lump of dough, as meticulously researched as any doctoral thesis, but also a Proustian personal memoir that hints of James Joyce, no less, in the way Silver intones and uses the rhythms of Aramaic Jewish liturgy, Yiddishkeit, and Yiddish humor to tell her story,” Schwartz said on the book’s website.

During her research, Silver discovered that the knish has connections to sources as surprising as Eleanor Roosevelt and rap music. One of her favorite stories in the book is about Gussie Schwebel, a former knish maker on Houston Street in New York. Schwebel wrote to Roosevelt to ask her to sample her knishes.

“They turned her away because there was too much press,” Silver revealed. “Mrs. Roosevelt’s secretary thought it was a public relations stunt. I say hats off to Mrs. Schwebel, because she had the chutzpah to write to Roosevelt. She wanted to help her adopted country so she asked to cook knishes for the armed forces. She used what she had, a knish, a food, and she ramped it up. That was in the 1940s. Later on she was quoted again in the Washington Post saying that knishes are going to bring about world peace and put an end to the Cold War. She saw food as an instrument for political maneuvering. Good for her.”

Where are Silver’s favorite places to buy a knish?

“The best knish you can get is one you make yourself,” she said. “Barring that, I like the one at Gottlieb’s in [the Brooklyn neighborhood of] Williamsburg because they speak Yiddish behind the counter. I also like the ones at Pastrami Queen uptown [in Manhattan], and if you have a hankering walking down the street there’s Gabila’s. Knish Nosh also has some good knish shops in Queens, and there’s Yonah Schimmel’s Knish Bakery on Houston Street.”

Every culture does seem to have its wrapped pastries, and Silver calls them “knishin’ cousins.”

“Food is never just about food,” she said. “It was about identity, otherness, sameness. I never thought of the knish as anything unusual. The more I talk about it the more I realize everyone doesn’t know what a knish is. It’s a great moment for knish literacy.”

Silver was recently hired to teach a course at the Brooklyn Greenery, “Improve Your Knish IQ,” to give people a chance to expand their knowledge of the food.

“The knish is a simple food and it is accessible,” Silver said. “It is one that people yearn for even when they don’t need to eat simple food because it reminds them of connections that may be difficult to maintain, or obtain.”

The author is also set to appear at New York’s Museum of Jewish Heritage on June 15 to discuss her book with food writer Gabriella Gershenson. Gabriel Sanders, director of public programs at the museum indicated that what “King Arthur is to the knight, Laura Silver is to the knish. Never before has the potato pocket had such a devoted champion,” Sanders said.

By Robert Gluck/JNS.org