Nitrous oxide is the most frequently used inhalation anxiolytic in dentistry; it is also used in hospitals and operating rooms. Commonly called “laughing gas,” it has been studied extensively and generally agreed to be one of the safest modalities of sedation in dentistry. It also has a colorful place in the history of anesthesia in this country.

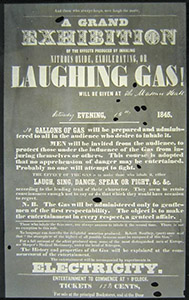

In the late 1700s, a chemist by the name of Joseph Priestley accidentally discovered nitrous oxide. He was combining nitric acid with different materials and noticed that after he added iron filings to the acid, a gas was produced that caused him to feel giddy and euphoric. Realizing the possible medical, as well as recreational, uses of this gas, Priestly and his apprentice invented a machine that could produce nitrous oxide in large quantities. Up until 1884, laughing gas was only used recreationally. It was demonstrated in fairs and marketplaces, and for upper-class “laughing gas” parties. In the 1830s, Samuel Colt—later the inventor of the Colt revolver—toured the United States and Canada with phony medical credentials. He would stop in town squares and let people inhale small amounts of nitrous oxide; he charged a quarter for adults and a dime for children. This provided hours of entertainment for the crowds that would laugh at people acting silly and loopy.

In 1844, a Connecticut dentist named Horace Wells was at one of these “laughing gas” parties, hosted by a showman named Gardner Colton. He observed that after inhaling the gas, one of the volunteers fell while laughing and stumbling across the stage, and in doing so seriously injured his leg. The man, however, did not seem to be in any pain; when Wells later spoke to the man he did not even remember hurting his leg. At this time there was no such thing as “painless dentistry,” and Wells was always looking for a way to make dental procedures easier to endure. Wells hired Colton to administer the gas to him while his partner in the dental practice extracted one of his teeth. Wells was ecstatic because he reported that he had not felt any pain during the procedure; he was sure that with the help of nitrous oxide, he could eliminate pain from dentistry.

In 1845, after about a dozen successful procedures using nitrous oxide on patients during procedures, Wells decided to demonstrate the technique at Massachusetts General Hospital for the benefit of Harvard Medical School students and faculty members. Unfortunately, the patient shouted in the middle of the tooth extraction due to the effects of the gas, and the audience booed Wells off the stage, calling him a swindler. This failed demonstration did nothing to persuade the crowd of physicians to pursue nitrous oxide sedation as a method of anesthesia. For the next few years Wells experimented with, and became addicted to, chloroform and ether. After constant exposure to those substances Wells eventually became deranged, and in 1848 he committed suicide.

Gardner Colton, the man who had originally inspired Wells, began to market nitrous oxide across the country directly to dentists soon after Wells died. By the late 1860s, Colton had administered the gas to thousands of patients safely and effectively. The medical community had begun experimenting with the gas as well, and thus began a new era in medicine and dentistry. In 1864 the American Dental Association, followed by the American Medical Association in 1870, officially credited Horace Wells with the discovery of anesthesia.

Today nitrous oxide is widely used to benefit many patients. When inhaled, the gas produces an analgesic effect that dulls sensation of pain, in addition to an anxiolytic effect, which creates a sensation of euphoria. Nitrous oxide has very few absolute contraindications; two of these are Sickle Cell Anemia and the MTHFR (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase) genetic mutation. Since the effectiveness of nitrous oxide depends on being able to breathe it through the nose, any upper respiratory infection or sinusitis would preclude its use. Generally it is recommended that a patient be on an empty stomach if they are being sedated with nitrous oxide since, on occasion, the effects of the gas can cause nausea.

In pediatric dentistry, nitrous oxide is beneficial not only to eliminate any fear and pain associated with a dental procedure, but also to enhance the overall experience. While many children may not show an outward fear of a visit to the dentist, even the most gentle and patient dentist cannot eliminate the uncomfortable aspects of the visit, such as the noises and sensations of the instruments. If a child requires treatment beyond the basic hygiene visits, the use of nitrous oxide can help make these visits a positive and even enjoyable experience. One of the most important aspects of pediatric dentistry is helping children grow into adults who do not fear the dentist, and nitrous oxide has proven to be an important tool in achieving that goal.

Talya Gluck earned her BA from Barnard College in 2004. She attended dental school at University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey and went on to complete a two-year Pediatric Dentistry residency in 2011. She is a board-eligible pediatric dentist and her research has been published in dental journals. She lives in NJ with her husband and three children.

By Dr. Talya Gluck