No matter how old you get, no matter how much you may have seen and done, it remains a singular experience to be in the same room with and hear the saga of a genuine Jewish hero such as Rabbi Yosef Mendelevich.

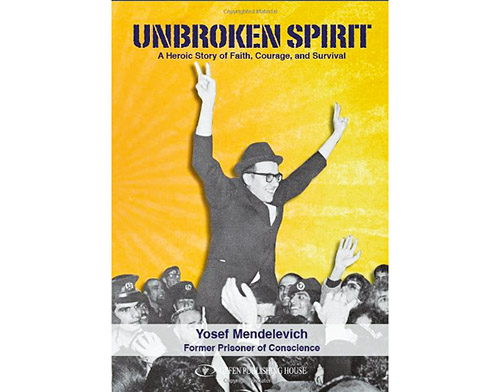

Mendelevich was the scholar-in-residence at Congregation Ahavas Achim in Highland Park on May 28. The rough outlines of his remarkable life story may be commonly known—a Jewish refusenik in the former Soviet Union in the 1960s, part of Jewish underground movement, caught with others in an effort to hijack a plane to Israel, sentenced to 12 years in labor camps, steadfastly maintained his Jewish identity in jail, released in 1981 and promptly relocated to Israel. Yet when you hear the specifics of his harrowing journey, you realize that you are in the presence of someone who exemplifies the best principles of Yiddishkeit and has done so in some of the toughest circumstances.

Mendelevich’s story began as he grew up in Riga, Latvia without much of a connection to observant Judaism, but part of a family proud to be Jewish. In the Soviet Union, any connections to Israel or religious activity were considered criminal and subject to prosecution. Many activities taken for granted in the United States, such as learning Hebrew, had to be done clandestinely to avoid detection. Despite the hardships, young Yosef thrived on his belief in Hashem and a love of the State of Israel.

This love was strengthened when he began weekly visits to clean up the Jewish cemetery just outside Riga, where some 50,000 Jews were buried in mass graves following their execution in 1941. Rather than finding the cleanup depressing, he found the camaraderie and Jewish pride inspiring, and he made an increased effort to be active in the “underground” groups of Jewish learning.

To fulfill his increased desire for Jewish observance, Mendelevich applied through legal channels to immigrate to Israel. Government officials denied the request because of his youth and the possibility that he would join the Israeli army and fight against his “Soviet brothers” who were then supplementing the armies of various Arab nations. Mendelevich knew that he would never be allowed to leave, as some flimsy excuse would be made at each life stage. Joining with some friends, one of whom was a former Soviet air force pilot, they made plans to hijack a small airplane to get to Israel. Their plans went awry and the KGB arrested the group before they boarded. After the group’s arrest, they were all sentenced to prison, with Mendelevich receiving a 12-year sentence.

In one of his talks Mendelevich shared anecdotes from his first days in the labor camp, which helped frame his approach to his imprisonment. He told a fellow refusenik who was imprisoned with him that he intended to maintain his Jewish identity in prison, and this friend said, “It is impossible to keep mitzvot in Soviet prison.” Mendelevich replied: “Whatever is next to impossible but not impossible is actually possible. And I intend to do it.”

When he initially arrived at the labor camp, he met Shimon, a younger man who was also imprisoned for his Jewish activities yet who lacked much knowledge of his Jewish identity. Shimon knew that Mendelevich had a better sense of their Jewish heritage and insisted that Mendelevich teach him, that night, about the things he needed to do to be authentically Jewish. Mendelevich spoke to Shimon about a few things, including the practice of wearing a kippah, then wondered aloud where they could find material to make kippot. Shimon said, “No problem, I have an extra pair of pants,” and the two men cut out kippot to wear.

It was that kippah that got Mendelevich in trouble repeatedly with prison authorities. In one particularly heartrending tale, Mendelevich told about how his father traveled hundreds of miles to visit him in prison and awaited him in a particular room. As Mendelevich walked to that room, a guard insisted that he remove his kippah or the visit would be canceled. When he resisted the guard’s demand, the guard removed him from the building and called off the meeting. A similar result took place when his father came for a second visit. From that point on, Mendelevich never saw his father before he died.

In his different talks at Ahavas Achim, Mendelevich shared other anecdotes of his remarkable and creative efforts to strengthen his Jewish identity in prison—to keep Shabbat, to avoid eating treif meat, to obtain a siddur and copy the pages for secret use, to hold a Pesach Seder, and to carve out time to daven. He also described the reactions when prison authorities discovered his efforts, including being placed for long solitary stays in “the punishment room.” Despite the hardships, he kept seeing God’s hand in his life.

One effort he undertook eventually led to his release; he started a hunger strike after the authorities took away his siddur. He publicized his hunger strike through the Jewish underground and the results were that after a few weeks, international pressure led the Soviets to return the siddur and then to transfer him to a prison in Moscow.

One attendee at the scholar-in-residence Shabbat, Artur Shnayder, shared this anecdote from the talks with The Jewish Link: “When Mendelevich was taken to the KGB jail in Moscow, he appeared before a tribunal and a Russian officer told him that he was losing his Soviet Union citizenship for numerous crimes and would be expelled from his homeland. Mendelevich was very happy. The officer said that [Aleksandr] Solzhenitsyn (one of the top dissidents) wept at the same news and wondered why Mr. Mendelevich was so happy. Mendelevich replied that for Solzhenitsyn, Russia is the real homeland, and for the Jews, Israel is the homeland. The officer said, sadly: “You Jews always find a way out of any situation.”

When the Soviets were driving him to the airport to expel him, Mendelevich told the KGB agent who accompanied him: “You know you miscalculated. You prevented us from taking a plane, now you are buying my ticket to leave. You meant to discourage Jews from trying to leave the USSR, now 20,000 leave each year.” The KGB agent conceded. “You are right.”

Andrew Getraer, former executive director of Rutgers Hillel, commented at the book signing on Saturday night that “I have heard many speakers covering many topics over the years, but none of them moved me as much as these presentations by Rabbi Mendelevich.”

Rabbi Steven Miodownik, rav of Ahavas Achim, noted: “Rabbi Mendelevich said that he wasn’t a hero and that he was just like all people in the audience. If I were in his shoes, I would hope I had his strength of character and perseverance, his absolute love of Torah and mitzvot under the most adverse of conditions. He is a lesson for all of us and someone we should never forget.”

Mark Stein of Highland Park attended all the lectures with his wife, Rachel. He said: “We take the ability to perform mitzvot for granted. Rabbi Mendelevich’s devotion to religious observance is the real deal.”

By Harry Glazer and Deborah Melman