Note: This is the first of an occasional series presented by the YU Center for Israel Studies.

There is only one American historian of Judaism who, at 11 o’clock on June 5, 2012, came face-to-face with the world’s famous ancient ruin. He is a scholar of Jewish antiquity who led an international team intent on understanding the Arch of Titus through state-of-the-art technology, demonstrating that the menorah was of golden color. He has written exhaustively on the history of the Arch of Titus, making him a leading authority. My excitement is likewise sprinkled with tears of joy, realizing that I have been given this opportunity to ask Professor Steven Fine of Yeshiva University questions about the myths of the menorah at the Vatican.

Our evidence for the disposition of the Temple vessels after the destruction of the Temple comes from two complementary sources, Josephus’s “Jewish War” (completed circa 75 CE) and the Arch of Titus in the Roman Forum today, completed circa 81 CE.

Bohen: I am often asked by tourists if the menorah is hidden underneath the tomb of St. Peter, or perhaps in the vaults of the secret archives.

Fine: The legends of the menorah at the Vatican are amazingly potent.

Nothing is left of the golden menorah and showbread table which, in 191 CE, were likely destroyed when a fire ravaged Vespasian’s Temple of Peace. Conflicting Christian legends have it that in 410 CE, when the Roman Empire was sacked by the Visigoth King Alaric I, he took the Temple treasures with him. The rest, including the menorah, were allegedly moved to Carthage in North Africa in 455 CE after yet another sacking of the city by King Gaiseric of the Vandals.

The most popular legend during the 19th century was that the menorah was thrown into the Tiber River and rests there in the sludge. There was even an attempt to dredge the bottom in search of it! Most fascinatingly, a large modern ashlar seems to have been buried in the soil of the Ghetto in Rome somewhere around 1900. It was discovered only in 1994. The ashlar is inscribed with a large menorah, and an inscription in Latin and in Hebrew: “Here lie the three brothers of the Jewish faith, Natanel, Amnon and Elia, who found the relics of Jerusalem, the candelabrum and the ark, in the Tiber, where they still are, three hundred seventy-five steps under the island, in correspondence with the promontory of the Palatine, they were beheaded by public ax under Emperor Honorius.” Whoever created this stone clearly hoped to provoke a search for the menorah, even providing directions on how to find it.

Bohen: It is my understanding that tabbinic sources have supposedly located the Second Temple vessels in Rome. Are these sources taken by people today to suggest that the menorah and the other Temple vessels are “hidden” at the Vatican? Since they were in Rome in antiquity, and Jewish sources provide no indication that they have been removed, then where else could they be?

Fine: Yes, early rabbinic sources describe the menorah, Temple curtain and other vessels in Rome, and these texts probably reflect reality. This is one example, describing travel by a mid-second century rabbi from Israel: “Said Rabbi Shimon: ‘When I went to Rome there, I saw the menorah’” (Sifre Zuta, Numbers 8:2). I can imagine Rabbi Shimon visiting Vespasian’s Temple of Peace to examine the lampstand.

Later sources have it that those vessels are “still” in Rome. That is, during late antiquity they were “still” (adayin) there: “The grinding tool of the house of Avtimas [used for making incense] and the showbread table and the menorah and the curtain and the headpiece [of the high priest] are still in Rome” (Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan A, ch. 41).

For historical readers, “still” is forever. Medieval Jewish and Christian legends had it that Temple vessels were hidden in a cave, though the source, Benjamin of Tudela (12th century), does not report actually seeing them. For some moderns too, the menorah is “still” in Rome.

Bohen: Some contemporary Jews believe the menorah is hidden somewhere in the Vatican. How did this menorah myth originate?

Fine: This is a modern story, one that I explore in my book “The Menorah: From the Bible to Modern Israel” (Harvard, 2016). It does not show up in Jewish literature until the post-War era, though retellings of tales about rabbis sometimes are set in the early 20th century.

The menorah at the Vatican is an urban legend, often believed by people of goodwill who really want the menorah to exist. For them, the menorah is the symbol of the Jewish people—all the more so once the Arch of Titus menorah was chosen for the symbol of Israel. This decision opened a new pathway, making the arch menorah all the more present—on government buildings, passports, official documents, and on all sorts of textbooks and posters. In 1949 placement of the state “symbol” above the door of the Israeli embassy in Rome was taken by some to be a kind of triumph. In that way, it is far more than the legend of the menorah in the Tiber. As long as the menorah exists, some tie with eternity is maintained.

It is a relic seen and unseen—seen in the arch and seen in Raphael’s painting of Heliodorus in the Temple at the Vatican and seen in the Jewish catacombs and in Rome’s museums, but unseen in its golden brilliance. It is a symbol of the State of Israel, called in Israeli liturgical texts “the first flowering of our redemption,” but not the hoped-for messianic kingdom for which all traditionalist Jews wait. When the menorah is restored, many believe, the messiah will be that much closer. The Vatican menorah myth is the newest stage in the long Jewish and Christian “search” for the Temple vessels. It is a Jewish version of the Holy Grail, the stuff of Dan Brown’s “The Da Vinci Code”…

Bohen: The menorah and the golden Table of the Showbread, taken as war spoils at the Jerusalem Temple are of particular importance to Jews and Christians. Ten years ago (June 5-7, 2012) you were standing on the scaffolding within the Arch of Titus, just inches from its gray stone. You and an international team found traces of yellow ochre on the arms and the base of the menorah, a monumental achievement in polychrome studies, Roman and Jewish studies. With this being said, do you think the myth of the menorah hidden in the Vatican will continue to be a topic of controversy for future generations?

Fine: As I said, there are so many images of the menorah in Rome—in churches, synagogues, the Arch, the Jewish catacombs, the Jewish Museum and the Vatican Museums. Some were made by Jews, others are Christian lampstands. Visitors to Rome are surrounded by the menorah. This presence raises interest in this holy object and encodes it into modern Jewish tourism as a kind of Jewish pilgrimage to the Eternal City.

Since antiquity, Rome has been paired with Jerusalem in Jewish and Christian imaginations. As Freud scribbled on the face of a postcard showing the Arch, “The Jew survives it,” or as other modern Jews are wont to say as they stare up at the menorah carved in the Arch, “Titus, you’re gone, but we’re still here. Am Yisrael Chai.” While the Vatican menorah myth is relatively new, it is potent and enduring— an ill-conceived yet understandable projection of hopes and longings millennia old.

A longer version of this article appears at https://www.meer.com/en/70238-some-questions-to-professor-steven-fine

Brenda Lee Bohen is a historic preservationist and accredited tour guide in the Jewish Museum of Rome and the Vatican Museums. She tirelessly advocates for scholarship and the history of the Jews of Rome.

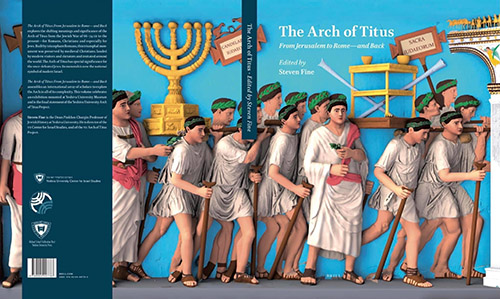

Steven Fine is the Churgin Professor of Jewish History at Yeshiva University and director of the YU Center for Israel Studies. He is the editor of “The Arch of Titus: From Jerusalem to Rome—and Back” (Brill and YU Press, 2021), yu.edu/cis