In Yevamot 110a, the Gemara discussed one of the small set of incidents in which Rav Ashi declares אַפְקְעִינְהוּ רַבָּנַן לְקִידּוּשֵׁי מִינֵּיהּ, that even though the man had performed betrothal (kiddushin), the sages uproot and that betrothal from him. There is controversy about the nature and extent of this rabbinic power and its applicability to solve modern instances of agunah. How does it work? Do these cases constitute a closed set, or is there some commonality between them such that it would extend to further cases? Could it be applied across the board, wherever useful? Were only Talmudic sages authorized to abrogate a betrothal, but declarations by modern rabbis lack the force? We won’t take up these questions here1, but exploring the sugyot with our unique focus might shed light on well-trodden ground.

As background, say a minor girl had been rabbinically married. If a girl’s father had died, her brother and mother can rabbinically marry her off to her spouse (which grants her financial stability). Upon reaching maturity, she can decide for herself whether to continue or annul the marriage. According to an explanation of Rav’s position, he’d maintain that the original rabbinic betrothal is in a state of suspension until she is old enough. Then, if they consummate the marriage carnally, it is affirmed. Otherwise, it is annulled.

Naresh is situated about 20 km southeast of Sura, where Rav presided. He reportedly said of its residents (Chullin 127a), “If a Nareshite kisses you, count your teeth.” In a case of stolen affections (Yevamot 110a), the rabbinically married girl achieved majority, and sat in the bridal chair (under a marriage canopy) with her spouse. Then, another man came, “grabbed her” from him and, with her consent, married her. Was she Biblically betrothed to the first spouse? To the second? The incident came before Rav Bruna and Rav Chananel and they declared that no bill of divorce was required from the second man, thus indicating that she was married to the first spouse. This decision, by Rav’s students, contradicts Rav’s statement.

Naresh Is Unique

Rav Pappa was a fifth-generation Amora, primarily Rava’s student but also Abaye’s. After Rava’s death, he established and headed an academy in Naresh. Rav Pappa resolves the contradiction by noting that בְּנַרֶשׁ מִינְסַב נָסְיבִי וַהֲדַר מוֹתְבִי אַבֵּי כוּרְסְיָיא, in Naresh, they first perform nuptials (consummating the marriage) and only afterwards seat her in the bridal chair.

What could account for this strange inversion? I am reminded of a similar arrangement in Judea. Yerushalmi Ketubot 1:5 relates that, in Judea, the bride and groom would consummate the marriage while she was still in her father’s household, and they would subsequently have the chuppah. This was due to Roman persecution, droit de seigneur2. Even after the governmental decree was removed, the custom persisted, and Rabbi Hoshaya’s daughter entered the chuppah pregnant. Perhaps the Nareshite custom stemmed from similar causes.

A few other details about Naresh, where underlying reality impacted Halacha. Rav declared that women may only immerse in the mikvah at night, so as not to mislead others into thinking that premature immersion during daytime of the seventh is valid. However, in Naresh, Rav Idi (bar Avin, see manuscripts; otherwise, of Naresh) instituted immersion in the daytime of the eighth day, because of concern for lions (Niddah 67b). The Naresh area was also steep (מוּלְיָיתָא), causing premature aging in people and animals (Eruvin 56a), which could also lend credence to certain ketubah claims (Yerushalmi Ketubot 1:1) and to public domain status (Eruvin 22b).

A Suran Explanation

I’d suggest another possibility, that the second-generation Rav Bruna and Rav Chananel, in proximity to Sura, operated within a Suran rather than Pumpeditan framework. On Yevamot 89b, Rav Chisda (second/third generation Amora of Sura) asserts that rabbinic law takes hold even on a Biblical level, such that a bastard by rabbinic law may marry a Biblical bastardess. Rabba (third generation Amora of Pumpedita) disagrees, and says it rabbinic law doesn’t impact Biblical law. Rav Chisda sends proof to Rabba via messenger, the Suran Amora, Rav Acha son of Rav Huna. One proof proffered by the Talmudic narrator (90b) is that, if the husband sends a get via messenger and then nullifies it en route, his wife is still divorced. By Torah law the get was invalid, yet due to rabbinic decree, she may remarry! The Talmud answers3 on behalf of the Pumpeditan perspective, based on Rav Ashi, that since people betroth based on the sages’ intent/authorization, the sages can abrogate the original betrothal.

Now, the proof Rav Chisda sent via Rav Acha son of Rav Huna regarded rabbinic marriage of a minor, where according to Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai, prior to carnal consummation, her husband rather than father inherits her. If we don’t credit Nareshite custom, the case of the snatched bride is roughly parallel. Rav Chisda could say that her rabbinic marriage has Biblical impact, so the snatcher’s betrothal couldn’t take hold.

A Pumpeditan Perspective

Rav Pappa is well-positioned to know Nareshite custom, so I find his answer rather persuasive. Despite this, his sixth-generation student, Rav Ashi (situated in Sura), proffers an alternative. Perhaps Rav Ashi would rather avoid establishing the ruling as narrow, with nothing to teach. Perhaps he felt a difficulty in retrojecting fifth-generation Nareshite custom to third-generation Naresh.

In Pumpedita, Rabba’s student was Rava. Rava’s student was Rav Pappa. Rav Pappa’s student was Rav Ashi. Now, Rav Pappa studied in Pumpedita but established his academy in Naresh, near Sura. And, Rav Ashi re-established Sura academy. They were thus familiar with Suran/Nareshite case law, but wished to explain it from a Pumpeditan perspective.

Therefore, Rav Ashi declares (110a) הוּא עָשָׂה שֶׁלֹּא כַּהוֹגֶן לְפִיכָךְ עָשׂוּ בּוֹ שֶׁלֹּא כַּהוֹגֶן, וְאַפְקְעִינְהוּ רַבָּנַן לְקִידּוּשֵׁי מִינֵּיהּ, The bride-snatcher acted improperly, so the Sages act “improperly” with him, and abrogate his betrothal. Ravina (I or II, either Rav Ashi’s student or Rava’s student) challenges Rav Ashi that while nullifying betrothal via money could work, how could they nullify betrothal via intercourse. And, an anonymous answer (implicitly Rav Ashi; some manuscripts have אמר ליה) explains how such nullification would work, that they transform the intercourse into licension intercourse rather than something effecting betrothal. Thus, by causing the betrothal money to be ownerless, the snatcher was never married even Biblically4. By declaring the intercourse licentious, it doesn’t work for betrothal; the same approach might transform the betrothal money into a mere gift.

Next column, we’ll explore Rav Ashi’s idea of abrogating betrothal diachronically. We’ll examine all six sugyot in which it appears, and discover how it was applied first by his son, then extended by the Talmudic narrator to three other cases.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 See Rabbi Shlomo Riskin’s Hafka’at Kiddushin: Towards Solving the Agunah Problem In Our Time in Tradition for a good summary of its historical application. There is much back-and-forth on this issue.

2 Contrast Bavli Ketubot 12a, where Rabbi Yehuda explains that in Judea, the bride and groom were secluded briefly before the wedding canopy, to grow accustomed to each other and reduce awkwardness later at marriage consummation. And compare Ketubot 3b, Rabba gives droit de seigneur is the cause for adjusting the Wednesday marriage day.

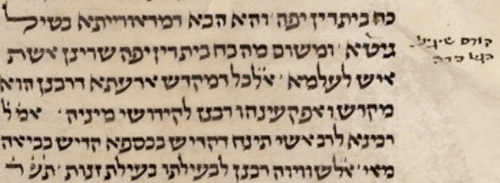

3 This segment seems from the Talmudic Narrator, unless we say that the anonymous rebuttal was Rabba’s own retort to Rav Chisda. Several manuscripts (Vatican 110, Munich 95, Munich 141) actually insert an אמר ליה, but I believe this easy insertion was lacking in the original, and each תא שמע after בְּעַאי לְאוֹתוֹבָךְ: עָרֵל, הַזָּאָה… is the Talmudic Narrator’s innovation. The anonymity also matches the structure of parallel sugyot, and the precise mechanism of abrogation of prior marriage seems more complex and derivative, as I’ll discuss in the next column. Still, this case is discussed in Yerushalmi Gittin 4:2, with a Rav Chisda-like explanation about rabbinic overriding Biblical law. After writing this and next column, I discovered that Shamma Friedman in HaIsha Rabba also argues that all proofs are discussed by Rabba and Rav Chisda.

4 Alternatively, if betrothal via money is divrei soferim, the Sages can abrogate the quasi-rabbinic snatcher’s betrothal. But see Rashi to 90b, d”h amar leih.