When breast cancer is caught early, treatment is less invasive and the prognosis is better. Government, medical societies and advocacy groups differ in some areas on the best way to screen women for early detection of breast cancer, but several recent developments are bringing them closer to each other.

On Monday, May 9, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force posted a “draft recommendation statement” that women should start getting mammograms at age 40, instead of the previous recommendation to start at age 50, but still recommends biannual screening. They based their decision to lower the starting age on studies that show a 19% reduction in breast cancer when mammography is begun earlier. The task force is now more closely aligned with recommendations from other major medical societies. The American Cancer Society recommends optional annual screening for women age 40 to 45 and annually thereafter. The American College of Radiology (ACR) advises women at average risk to start mammography at 40 and get a mammogram annually. In a new update on May 3, ACR updated its guidelines to recommend that all women, particularly Black and Ashkenazi Jewish women, have a risk assessment by age 25 to determine if screening earlier than age 40 is needed. Jewish women with Ashkenazi heritage have a one in forty chance of having a mutation in the BRCA1 gene that increases the risk of developing breast cancer.

In another ruling, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration updated federal mammography regulations on March 9 to require all mammography facilities to inform patients whether they have dense breasts in a letter sent with their exam results. Thirty-eight states and the District of Columbia have laws requiring mammogram providers to notify patients about breast density, but the language, and mandate for insurance coverage, is different in each state.

What is breast density and why do we need to know about it?

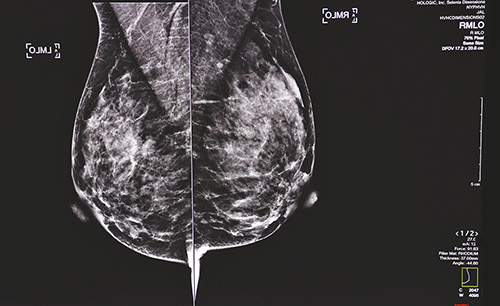

Dr. Mindy Goldfischer, chief of breast imaging at The Leslie Simon Breast Care and Cytodiagnosis Center at Englewood Health, explained the problem in an email interview: “Dense breast tissue is composed of glandular and fibrous tissue which appear white on a mammogram. Fatty breast tissue appears gray. Unfortunately, like dense breast tissue, breast cancers appear white on mammogram. Therefore, breast cancer can be hidden, or hard to find.” It is said that looking for cancer in dense breasts on a mammogram is like looking for a snowflake in a snowstorm. On an ultrasound picture, cancer appears gray in the white tissue. Density has also been cited as a risk for developing cancer although it is not known yet why. Dr. Goldfischer noted that before menopause, more than half of women have increased breast density, and the incidence of breast cancer is lowest in this demographic.

A mammogram is still considered the gold standard of breast detection, and should be the first screening tool for all women, even women with dense breasts. Some cancers, such as those that develop in calcifications, can only be seen on a mammogram.

After JoAnn Pushkin’s cancer was missed on a mammogram, and found when it was more advanced, she began advocating for a breast density inform bill. She was shocked to learn that breast density both increased her risk of developing breast cancer and that the cancer could be missed on a mammogram. “A double whammy,” as she described it. She wrote to the FDA in 2010 asking for density notification to be required in the letters sent to patients with their mammography results. They agreed and asked her to testify at a hearing in 2011. As a result of her efforts, a New York state law was enacted in 2012 to notify women if they have dense breasts and that dense breasts can hide cancers and increase risk. Pushkin has continued to advocate for education on the topic and for women to know about breast density. She co-founded the website DenseBreast-info.org (DBI) (https://densebreast-info.org) to educate women, medical professionals and legislators about breast density.

In 2019, the FDA issued the proposed ruling for a federal breast density notification and initiated an “open for public comment” period. The DBI organization submitted feedback and a detailed analysis. Pushkin credits Senator Dianne Feinstein and Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro, whom she calls heroes, for pushing the FDA forward. “The DBI website has a dedicated FDA page that has information about the new rule, what the letter should say, and includes information about how to contact the FDA with any questions,” she said. Pushkin also advocated for another piece of recently introduced federal legislation, the Find It Early Act, that would ensure all health insurance plans cover screening and diagnostic imaging with no out-of-pocket costs for women with dense breasts or at higher risk for breast cancer.

While Pushkin is pleased that a federal density law has finally been enacted, there is still work to be done in the 18-month period all states have to begin complying with the law. “State laws vary and that is the reason we needed a single, national reporting standard,” she said. “The FDA has developed two letters: one for dense women and one for not-dense women and they must be used verbatim so all women getting a mammogram in a United States mammography facility will receive either one or the other letter. It creates a baseline standard of consistent information that all women will be provided.” Pushkin said states can keep their current language if not in conflict with the FDA statement. “Each state will have to review their language to see if it is in conflict.”

That could be the case in New Jersey. New Jersey enacted a breast-density notification law in 2014. The original bill required women to be notified about their results, but after opposition from the New Jersey section of the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the state insurance industry, the language was rewritten into this generic statement: “Your mammogram may show that you have dense breast tissue as determined by the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System established by the American College of Radiology.” Complete results are sent to the patients’ referring doctors and women are advised to ask them about their density and any additional screening needed. The law does require insurance to cover supplemental screening when women have extremely dense breast tissue or other additional risk factors.

The impetus for a New Jersey breast-density law was Teaneck radiologist Dr. Lisa Weinstock. She first observed that breast density could obscure cancers on a mammogram during her breast-imaging fellowship at Columbia University Medical Center in 1994. Performing ultrasound on patients with dense tissue was not standard practice at that time, which is one of the reasons she opened Women’s Digital Imaging in 2004. In 2011 she testified in Virginia before the FDA in support of a federal density notification law.

Without any clear timeline for federal legislation, Dr. Weinstock actively sought to get a breast-density notification bill

enacted in New Jersey. She began by contacting Senator Loretta Weinberg, who enthusiastically supported and introduced the legislation. Full disclosure: I was a public relations consultant for Dr. Weinstock and attended the meeting with Senator Weinberg and a meeting of the New Jersey Assembly in which Dr, Weinstock testified in support of the proposed legislation. Dr. Weinstock was disappointed in the final wording of the law but said it did open up awareness and conversations about breast density and breast cancer risk.

Dr. Weinstock closed her practice in 2021 and currently works with New York-Presbyterian/Columbia facilities. She welcomes the new federal density notification law but thinks patients and their referring doctors would benefit from more education about imaging dense breasts and would like to see widespread implementation of breast cancer risk assessment.

Pushkin said DBI has developed a comprehensive continuing education course for physicians, “Dense Breasts and Supplemental Screening,” which offers free AMA or ASRT credits. “The referring provider really is the gatekeeper for a woman to get supplemental screening because they have to write the order,” said Pushkin. “They need to understand the screening and risk implications of dense tissue. They need to know how to identify the high-risk patient and what to do if she is a high-risk patient.”

Dr. Goldfischer said it is important for women to know their personal risk of breast cancer, which is determined by multiple other factors including age, family history, specific genetic mutations, age of their first childbirth and exposure to chest radiation at a young age, among others. “With a detailed history, a risk score is calculated,” she wrote. “Women who have a risk score of 20% or higher may be advised to have annual breast MRIs in addition to their annual mammography. Women with a lifetime risk between 15% and 19% may be advised to have annual breast sonograms in addition to their annual mammogram.”

Pushkin encourages anyone who wants to know more about breast density to visit https://DenseBreast-info.org. Women who don’t know their breast density or genetic profile should contact their doctor to ask about getting a risk assessment for breast cancer, followed by a discussion on how, and how often, they should be screened. The regulations and recommendations issued recently, though not yet fully in force, should help guide these conversations.