There is a fundamental disagreement between fifth-generation Tannaim, Rabbi Eleazar (ben Shamua) and Rabbi Meir, about what aspect of writing a bill of divorce needs to be written lishma, with intent. Devarim 24 discusses the prohibition of a man remarrying his divorcée if she has remarried another, and so verse 1 and then verse 3 discuss the process of divorce. These details include וְכָ֨תַב לָ֜הּ—he writes for her, סֵ֤פֶר כְּרִיתֻת֙—a bill of divorce, וְנָתַ֣ן בְּיָדָ֔הּ—and places it in her hands, וְשִׁלְּחָ֖הּ מִבֵּיתֽוֹ—and sends her from his house. Each of these phrases are interpreted—sometimes in different ways—and we should realize that there are actually two instances of each phrase available for derasha.

The phrase וְכָ֨תַב לָ֜הּ is taken to indicate that the get must be written specifically for her to effect this divorce. Now, Rabbi Eleazar maintains that עֵדֵי מְסִירָה כָּרְתִי, what actually effectuates the divorce is the handing over of the document in the presence of two witnesses. The “essential” portion of the document needs to be written lishma. Let’s assume1 this is the toref (תּוֹרֶף)—the part with her and his name and the date—which distinguishes this get from all others, and after all contains her name and would be what you’d expect to be written for the purpose. The other, “standard” portion of the document, called the “tofes” (טוֹפֶס), describes how this is a divorce, and doesn’t differ from get to get. The tofes need not be lishma, in theory on a biblical level. Nor are written signatures necessary. After all, it is the act of handing over of the document that effectuates the divorce (or an IOU) take effect, and the document doesn’t have to stand up in a court of law to prove divorce (or the loan’s existence).

In contrast, Rabbi Meir maintains that עֵדֵי חֲתִימָה כָּרְתִי—the important witnesses are those to the signing of the get. We might conceive of this as creating a shtar ra’ayah, a valid document which can be used as proof that they are divorced, and then transferring that proof to the woman. She could use this document as evidence to remarry, or to collect her ketubah, so this is effectuating the divorce. For Rabbi Meir (Gittin 26b), as interpreted by Rav Nachman2, there’s no lishma aspect for any actual writing of get’s text. The husband can even find the get in the garbage (with his and her names coincidentally written on it). The only aspect requiring lishma, from וְכָ֨תַב לָ֜הּ, is the witnesses’ signatures.

Our mishna (Gittin 26a) discusses a tofes written in advance, with a two or three-way dispute. The anonymous Tanna Kamma requires space for the man’s name, woman’s name and the date on a get—that is, the toref. For bills of sale, one leaves space for the buyer, seller, the money, the field, and the date—the toref—because of the “ordinance.” Rabbi Yehuda invalidates all of them (if the tofes was written in advance). Rabbi Eleazar validates all of them, except for bills of divorce, because it is stated וְכָתַב לָהּ—thus, lishma.

The Mishna’s formulation seems strange, because Rabbi Eleazar is invalidating a prewritten tofes based on וְכָתַב לָהּ. Yet—the Talmudic narrator notes—we know that it is the toref, the essential portion with the names, that וְכָתַב לָהּ indicates the need for lishmah. The narrator answers that we need to factually or mentally amend the mishna’s text, adding “mishum.” Thus, מִשּׁוּם שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר וְכָתַב לָהּ—לִשְׁמָהּ. As Rashi explains, this indicates a rabbinic decree. Because וְכָתַב לָהּ set the biblical requirement for the toref, the Sages added a lishmah requirement for the tofes as well.

Likely due to my lack of comprehensive expertise, if I had my druthers, I would have said that for Rabbi Eliezer, the essential portion of the get was the tofes—the standardized portion. After all, the tofes expresses the husband’s desire to divorce in written form, and could be the סֵ֤פֶר כְּרִיתֻת֙ which he writes with intent. He then places it into her hand, effectuating the divorce. I would say that the details of his and her name, and the date are utterly irrelevant, the same as the witnesses’ signatures are utterly irrelevant since the point is not to create a valid shtar ra’ayah3 ! Perhaps for Rabbi Meir, the essential portion is the toref, but for Rabbi Eleazar, it should be the tofes. And then, the derivation in the mishna is perfect.

Expansive Storytelling

Rabbi Yossi HaGlili’s interpretation of סֵ֤פֶר כְּרִיתֻת֙ was (Gittin 21b) restricting the physical type of document; the Talmudic narrator explains that the Sages—his disputants—took this to require סְפִירַת דְּבָרִים, an account of the matter of divorce, perhaps a mere account. Alternatively, of course, a valid get requires that simple level of description. So—Ran explains—the derasha teaches you would require an over-and-above description. This would mean including all nicknames and aliases in various cities in the toref.4

Alternatively—as the mishna (Gittin 85) explains—the main text of the get is הֲרֵי אַתְּ מוּתֶּרֶת לְכׇל אָדָם—“Behold, you are permitted to many any man.” But, Rabbi Yehuda requires an additional text, וְדֵן דְּיֶהֱוֵי לִיכִי מִינַּאי סֵפֶר תֵּירוּכִין וְאִגֶּרֶת שִׁבּוּקִין וְגֵט פִּטּוּרִין לִמְהָךְ לְהִתְנְסָבָא לְכֹל גְּבַר דִּיתִצְבִּיִּין—“And this that you shall have from me is a scroll of divorce, and a letter of leave and a bill of dismissal to go to marry any man that you wish.” While Nedarim 5b and Gittin 85b try unsuccessfully to fit this into the framework of requiring “yadayim mochichot,” this may simply be the aforementioned extraneous סְפִירַת דְּבָרִים within the tofes. (Thus, טָפַסְתָּ מְרֻבָּה.)

Furthermore, in Aderet Eliyahu, the Vilna Gaon’s students quote him as explaining that the Torah sheba’al peh has an additional level of interpretation5 of Devarim 24:1-2 in which each phrase—when understood with its halachic implications—parallels Rabbi Yehuda’s expansive formulation. Rav Herschel Schachter conceptualizes this as if the verse’s punctuation were changed. Thus, וְכָ֨תַב לָ֜הּ סֵ֤פֶר כְּרִיתֻת֙ וְנָתַ֣ן בְּיָדָ֔הּ וְשִׁלְּחָ֖הּ מִבֵּיתֽוֹ וְיָצְאָ֖ה מִבֵּית֑וֹ וְהָלְכָ֖ה וְהָיְתָ֥ה לְאִישׁ־אַחֵֽר has a colon after סֵ֤פֶר כְּרִיתֻת֙, so that the verse instructs that he write סְפִירַת דְּבָרִים יְתֵירִים—namely the halachic details. For instance, לְהִתְנְסָבָא לְכֹל גְּבַר דִּיתִצְבִּיִּין matches לְהִתְנְסָבָא לְכֹל גְּבַר דִּיתִצְבִּיִּין. I’d personally move the colon even earlier, to follow וְכָ֨תַב לָ֜הּ. After all, סֵ֤פֶר כְּרִיתֻת֙ parallels Rabbi Yehuda’s סֵפֶר תֵּירוּכִין. Unless an asmachta, this seems a biblical-level instruction to write this text—either the simple or expansive level of description in the tofes. Should this description be written lishmahas well?6

Omitting ‘Lishma’

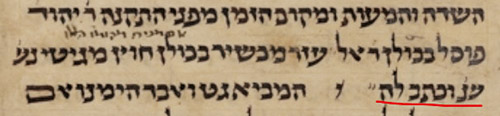

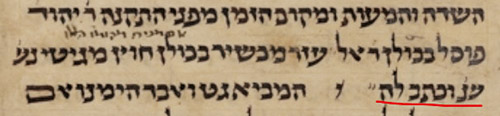

Our text in the mishna, where Rabbi Eleazar says שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר וְכָתַב לָה—לִשְׁמָהּ, is found in the Vilna printing and among manuscripts, Munich 95, Firkovitz 187, Vatican 140 and the Kaufmann mishna. However, in Soncino and Venice printings and the Vatican 130 manuscript, לִשְׁמָהּ is missing.

In the Geonic piska—excerpting the mishna for discussion—all printings and manuscripts except for Vatican 140 omit לִשְׁמָהּ, though perhaps an excerpt should be short. All printings and manuscripts of the Talmudic narrator’s מִשּׁוּם emendation include the word לִשְׁמָהּ. Without the word “lishma,” might this instead specifically target the brief or expansive sefirat devarim of the tofes?

Further Evidence

Consider Gittin 19b-20a: “A man came to the synagogue clutching a Torah scroll and gave it to his wife, saying, ‘Here’s your get!’ Rav Yosef said: What should we be worried about? If because of gall water used as ink on the back of the scroll, it isn’t permanent when written on a scroll treated with gall water. If because of the divorce written in it, we require וְכָתַב לָה—לִשְׁמָהּ and this is absent here. And, if you’re worried he gave money to the scribe beforehand to write that portion (Devarim 24) lishma, it’s still missing his and her name and city!” This analysis— from a named Amora—seems to apply Rabbi Eleazar’s לִשְׁמָהּ to the tofes, Devarim 24’s divorce description, not to the toref with their names.

Space considerations preclude analyzing and explaining counter-evidence. For instance, the preceding mishna discusses a get written by scribes for practice—which coincidentally has his and her names—as invalid7. Simply interpreted, this suggests the toref requires lishma for Rabbi Eleazar. We might explain the lishma concern is for the tofes, but a valid get requires correct names, so the case includes that coincidence. In a future article, we might explore the evidence more comprehensively, but until then, know this was a one-sided presentation.

1 As is made explicit at the bottom of Gittin 26a.

2 Or cited, depending on how we understand Rav Nachman’s statement אוֹמֵר הָיָה רַבִּי מֵאִיר.

3 And the same for an IOU, if he can effectuate an hitchayvut mammon by handing a standardized IOU in the presence of witnesses.

4 See Rav Schachter’s discussion in Gittin no. 44, yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.cfm/1060019/

5 See hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=14225&st=&pgnum=97

6 Recall Rabbi Yehuda in the mishna (26a) also invalidates every tofes written in advance.

7 Similarly, statements such as Shmuel on Gittin 23a: וְהוּא שֶׁשִּׁיֵּיר מְקוֹם הַתּוֹרֶף, about a deaf-mute who writes a get, within Rabbi Eleazar.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.