How can we live higher, live better? It’s a question I think about often as a therapist, a trainer, a child advocate, a writer, and of course in my personal life. It’s my passion to give children tools to help them thrive, and to build healthy confidence and skills in them. I ponder how we can best help our children build a mindset of strength accompanied by a sense of limits and responsibility.

When I read the books “The Choice” and “The Gift” by Dr. Edith Eger, I knew I had found a person who could be a beacon of inspiration for me, professionally and personally. Once a contender for gymnastics in the Olympics, Edith Eger was deported to Auschwitz at age 16. Her physical and mental training for becoming a champion served her in good stead as she withstood the horrors of the concentration camp and later immigration to the U.S. and her long journey to become a psychotherapist. During her schooling, she drew on her own experiences of trauma to help others heal and flourish. Having survived and thrived herself, she herself is a walking demonstration of how to pour pain into purpose.

Edith finished her doctorate at age 50. Today, at age 95, she lives in San Diego; she recently authored two books and still has sessions with clients! Age is a mental state, she said. She’s up on the latest technology and appears on podcasts and Zoom meetings.

I listened to an interview with Edith on Mondays with Moshe, a podcast for frum therapists. Then I read her books, stumbling upon one incredible quote after another. The pages quickly filled with yellow highlighter. A passion ignited within me to somehow meet her.

I shared my dream with my husband Naftoli, who has a way of making things happen. We decided to send her a children’s book I wrote, a book designed to help children deal with their own intense emotions, hoping it would intrigue her enough to grant us a meeting. I mentioned that I have a second book, this one on bullying, soon to be released. Somehow in my mind, there was a link between my work and hers; I kept thinking about how her tools could be shared with children. I don’t have a clear idea yet how that would work, but I’m still turning it over in my mind.

Edith’s assistants responded to our correspondence, but couldn’t guarantee a meeting. Winter break was coming up, and we decided to book a flight to San Diego anyway. One assistant told us she hoped it would work out. Another said, “Cancel your flight.” They told us that Edith had slowed down in the past month. Her sister Magda, who’d escaped Europe with her, had recently passed away at age 100. Edith herself was recovering from a bout of pneumonia. We decided to come anyway, determined to try our best to make it happen. If not, well, there was always the ocean and the San Diego Zoo.

We boarded a plane to San Diego with three of our children in tow, praying everything would work out. “We may not get to meet Edith,” we told them, “But in either case, this will be the trip of ‘The Choice’ and ‘The Gift.’”

In San Diego, we spoke to a principal of a Jewish girls’ high school. He told us that he brings one class a year to Edith, and has seen it produce miracles. There was one girl who had a difficult relationship with her parents. As Edith was speaking to the group, she looked directly at her and said, “No matter what, you really have to be there for yourself.” It helped this young woman turn around.

To our delight, we got a call not long after our arrival asking if we could be at Edith’s apartment the next day at 2:30 p.m. I was amazed and awed that the opportunity came through! Seeing her in person would concretize everything I’d read, and would make it real for my family!

We found her street without any trouble, which is in a beautiful neighborhood in the sunny hills of La Jolla. We walked through the trails of her garden to reach the front door, where we were met by Leanore, her executive assistant.

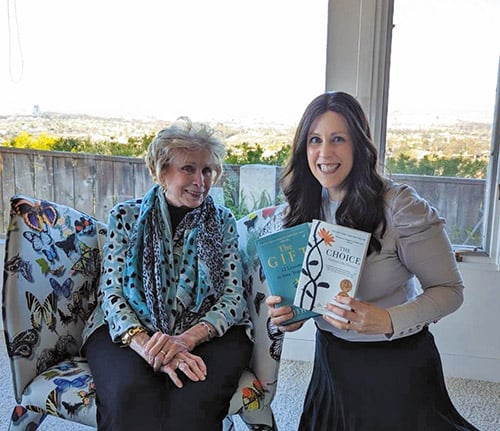

Walking into Edith’s apartment was an experience. It overlooks the serene, picture-perfect beach and is tastefully decorated in white. The living room has two chairs adorned with butterflies, which made me think of jewel-toned butterflies soaring high.

Edith came out to greet us, elegantly dressed in well-tailored clothing. She is regal. She has an air of calm authority and a warm, inviting, vibrant presence. Despite her recent challenges, she is independent mentally and physically, and walks with confidence. “How can I be helpful?” she said with a smile. She never says, “How are you?” she told us. She prefers to ask how she can be useful.

I told her I had been very inspired by her work, and hoped to incorporate some of her teachings into my own social work practice, and to glean some of the wisdom of her powerful mindset. I said we had read her books and dreamed of meeting her. I had visited Auschwitz in the 10th grade, and now realize my children will not have many opportunities to meet survivors.

Edith acknowledged Naftoli’s initiative in making our visit happen: “Either you are determined or foolish!” she said with a smile. She seemed to size me up, accurately, as a passionate social worker.

She began our meeting almost as if we were there for a therapy session, but quickly switched gears. She seemed very comfortable in her own skin and open to any question, eager and interested in speaking to us and our children. Our children felt comfortable asking her their many questions.

She said to Naftoli and I, “I have two questions for you. When did your childhood end, and would you like to be married to yourselves?” (Powerful questions!) Naftoli answered with a grin, “My childhood never ended.” Edith responded, “It’s good to be childlike, but not childish.”

Then we moved on to her own story. Edith was sent to Auschwitz at 16, after a childhood spent with her parents and two sisters. The family had minimal connection to Judaism, although they did eat challah on Shabbat and make a Pesach seder. During her teen years, she trained as a gymnast, hoping to go to the Olympics, but as antisemitism escalated in Europe, she was told that as a Jew she would no longer be able to compete. Her spirited response at that time was, “I will plot my revenge, but it won’t be one of hate. It will be the revenge of perfection. I will show my coach that I am the best.”

On her very first day in Auschwitz, Edith found out that her parents had been sent to the gas chambers. When one of our kids asked what it was like to hear that, we saw a flash of pain cross her face. We asked, “How did you continue to live with that pain?” She answered, “I had a fierce determination. I wanted to live no matter what.”

She spoke about being able to help her sister survive. Due to her athletic training, Edith was strong and lean, and didn’t require as much food as her sister. I asked her if she thought that the discipline and determination she had cultivated before the war, during her rigorous, five-hour-a-day training for the Olympics, helped her pull through. She agreed that this strength of mindset and body helped her to survive throughout her horrific journey.

As a child, her mother had told her how smart she was, and this became her own inner voice. “I am smart. I have brains. I will figure things out,” she would tell herself.

“The words inside my head made a tremendous difference in my ability to maintain hope,” she said. “That was true for the other inmates as well. We were able to discover an inner strength we could draw on, a way to talk to ourselves that helped us feel free inside.”

She spoke about the essential formula for survival: “To survive is to transcend your own needs and commit yourself to someone or something outside yourself,” she said. It caused me to reflect: isn’t that what we and our children need to do, not just to survive, but to thrive? We need a vision and a calling. We need meaningful goals so that we can use our individual sparks to ignite the world.

Edith speaks as articulately as she writes, and clearly chooses each word and memory carefully. I asked her, “How did you write your books? How did you remember everything, especially since you spent many years trying hard to forget?” She tells us that she always had an excellent memory and was able to remember all the details. In the same way that Victor Frankl, Elie Wiesel and others became the voice of male survivors of the camps, she hopes to be a voice for the women survivors.

Edith shared her journey of loss and postwar struggles of immigration, adjustment and raising her family in America. One of the last things Edith’s mother told her was, “No one can take away what you have put into your own mind.” It became a part of the foundation of Edith’s work with clients, using a method she calls “choice therapy,” and later her writing. She speaks of the prison in her mind as being worse than the prison of Auschwitz. Until she became intentional about embracing her feelings and challenges, the camps still held her prisoner. “Auschwitz was my teacher,” she said. “We have a choice to pay attention to what we lost, or pay attention to what we still have.” When she speaks of being victimized, she is now able to say, “But I am not a victim. I am a victor. I choose to thrive.”

“After you were freed from the camps, walking on the streets, people still spit at you and called you ‘dirty Jew,’” we said. “Yet you wrote that you felt compassion for them. Can you explain that?” Edith answered, “We are born to love. Hate is taught. I felt compassion for them, for the lessons they were taught.

“We cannot choose to live a life free of hurt, but we can choose to be free, to escape the past, no matter what befalls us, and to embrace the possible.”

In her words, stories and interactions, Edith shares this gift of choice. She has lived through the unimaginable, but she has made her choice, and that choice is to embrace joy. “That is freedom. Responsible means

response-able,” she says. There is a space between stimulus and response, she writes. Whatever the stimulus is, no matter how difficult, we can reset our minds to recalibrate and decide how we choose to respond. This is a skill that develops as we focus on it. It’s accessible to all of us.

Edith encourages us to make our choices and embrace the possible. “Our painful opportunities aren’t a liability — they are a gift,” she says. “They give us perspective and meaning, an opportunity to find our unique purpose and strength.” I find her example nothing less than heroic.

Surely this meeting will serve as a tool for me, for my children and the others we will share it with. We can all learn from Edith how to embrace our feelings and challenges so we can learn and thrive. In order to best honor those who died, we must live with intention. We must decide how we want to live and how to be our best. Edith told our children, “Before I speak, I ask myself three questions: Is it kind? Is it helpful? Is it important?” She also told them, “Don’t be dependent — be interdependent.” They soaked it up.

Despite her age and accomplishments, Edith spoke about the things she wants to do in the future — perhaps write children’s books, she said. It seemed eminently clear that she wants to keep living and contributing to the world as long as possible.

My husband asked her, “What legacy do you want to leave behind, what should our children remember and share?” She answered: “We must remember the Holocaust and not allow the persecution of our people again, and we must be proud to be Jewish!”

It pleased her that my copies of her books were well worn, and that I had really used them and marked them up. As we prepared to leave, I signed my children’s book for her, and she signed both of her books for me. She wrote, “Thank you, Yael, for being the Kindness Renaissance Woman of Strength. Shalom, Edie.”

I will treasure those books! I believe the opportunity we had to learn from Edith will be part of my family history forever. Edith has sometimes ended speaking engagements with a dancer’s high kick, and we felt that same energy and uplift as we left. She’s an inspiration to all of us!

Gems From Edith Eger

“We flourish when we harness learned optimism, the strength, resiliency and ability to create meaning and direction in our lives.”

“Awful things happen and they hurt. These devastating experiences are also opportunities to regroup and decide what we want in our lives.”

“You can’t heal what you don’t feel.”

“You either contribute to a relationship, or you contaminate it.”

“The opposite of depression is expression.”