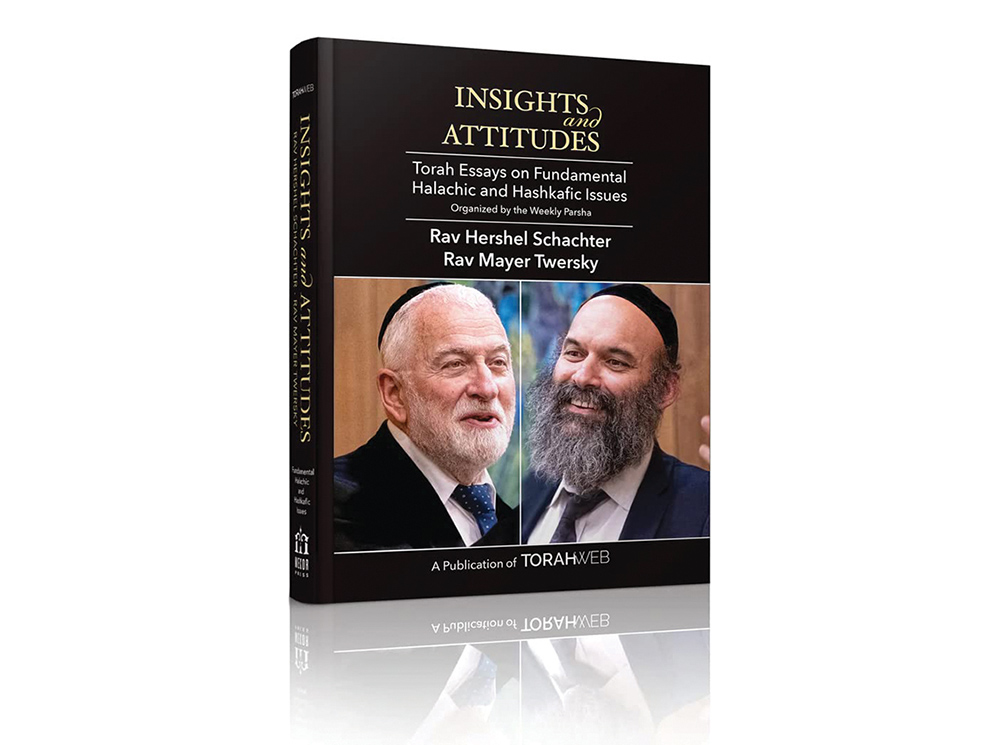

Editor’s note: This series is reprinted with permission from “Insights & Attitudes: Torah Essays on Fundamental Halachic and Hashkafic Issues,” a publication of TorahWeb.org. The book contains multiple articles—organized by parsha—by Rabbi Hershel Schachter and Rabbi Mayer Twersky.

The chachamim instituted that we read a haftarah every Shabbos, that deals with a topic which is inyana deyoma, issues of the day. Usually the haftarah will relate to a theme which appears in the parshas hashavua, as we consider that to be inyana deyoma. When Rosh Chodesh falls out on a Sunday, we consider Machar Chodesh to be inyana deyoma.

The second pasuk in the haftarah of parshas Eikev says:

גם אלה תשכחנה ואנכי לא אשכחך

“Those forget as well, but I (HaKadosh Baruch Hu) will not forget you (Bnei Yisrael).” The midrash sees an additional level of meaning in Hashem using the words, “eileh” and “anochi,” when telling Bnei Yisrael that He will remember us. Bnei Yisrael listened attentively when Hashem proclaimed, “אנכי ה’ אלקיך,” but then did not listen to Hashem when, at the time of the Cheit HaEgel, they used the expression, “אלה אלהיך ישראל.” The midrash explains that Hashem is telling us that He will forget about the Cheit HaEgel, but He will not forget about the zechus of ma’amad Har Sinai. How does one understand this selective memory on the part of Hashem?

The explanation is not all that complicated. In life, we all have people and places that we like and those that we dislike. All people definitely have maalos and chesronos. We like certain people and places because we feel that their maalos outweigh their chesronos. And the same is true in the people and places that we dislike. We recognize that they too, have maalos, but we have decided that their chesronos outweigh their maalos. One cannot lead a normal life by having a love-hate relationship with everybody, loving them for their maalos and disliking them for their chesronos. We always have to decide whether any particular individual is worth liking and then simply ignore their chesronos; or, perhaps, we should decide to dislike them and then ignore their maalos. The Ribbono Shel Olam has decided to love Bnei Yisrael because of the Avos (see parshas Eikev, Devarim 10:15 and 9:5) and, therefore, chooses to ignore all of their chesronos.

When we recite the Selichos, we mention that Hashem is מעביר ראשון ראשון. The Rambam explains (Hilchos Teshuva 3:5) that what this means is the following: when one’s sins are counted up to determine whether his mitzvos outweigh his aveiros or the reverse, for an individual (as opposed to the tzibbur), the first two sins are discounted. If after discounting the first two times, it turns out that his mitzvos outweigh his aveiros, all of the aveiros will be discounted because after discounting the first two aveiros, the third and the fourth are now considered as the first and the second and deserve to be discounted. Then, after they too, are discounted, the fifth and the sixth are now considered as the first and the second and, therefore, deserve to be discounted, and so on. This concept probably only applies to Bnei Yisrael, as they are basically—at their very core—full of ahavas Hashem and yiras Hashem in their spiritual DNA. Rebelling against Hashem and doing aveiros simply does not fit in with their personality at all. The aveiros that they do (when outnumbered by the mitzvos) are considered an anomaly and a quirk. It is for this reason that Hashem will forget the “eileh” and only remember the “anochi.”

Rabbi Hershel Schachter joined the faculty of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary in 1967, at the age of 26, the youngest rosh yeshiva at RIETS. Since 1971, Rabbi Schachter has been rosh kollel in RIETS’ Marcos and Adina Katz Kollel (Institute for Advanced Research in Rabbinics) and also holds the institution’s Nathan and Vivian Fink Distinguished Professorial Chair in Talmud. In addition to his teaching duties, Rabbi Schachter lectures, writes and serves as a world renowned decisor of Jewish Law.