Kiddushin 49a discusses conditional betrothal. If I betroth on condition that I’m a Kohen, but I am really a Levi, there’s no betrothal. The same if the condition is that I’m a Levi but really I’m a Kohen. A condition mentioned in a brayta is: that I’m a קַרְיָינָא, a reader. What makes a person literate (as the Koren translation has it), or a reader of scripture (as Artscroll)? He must be capable of reading three verses in the synagogue [So says Rabbi Meir ]. Rabbi Yehuda says he must both read and translate. The Talmudic Narrator interjects, for elsewhere Rabbi Yehuda says that one who translates verses literally is a liar. Rather, to be a reader, he must also recite the traditional Targum, (Onkelos’ translation), of the verses. The Talmudic Narrator adds: this is to be a קַרְיָינָא. However, to be a קָרָא, he needs to read Tanach with precision.

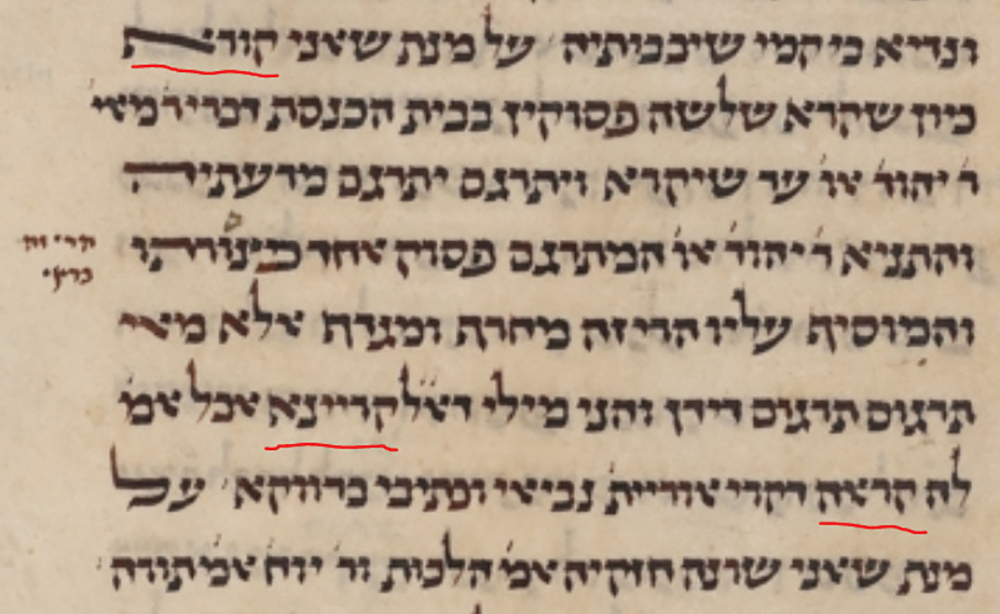

Girsologically speaking, it’s unlikely that the brayta had the Aramaic קַרְיָינָא. Printed texts have it, but manuscripts have קוֹרֵא, thus “that I can read” or “that I’m a reader.” Presumably the קַרְיָינָא was transferred from the Talmudic Narrator’s later use of the term as a synonym. So, the distinction is korei/karyana against kara/kara`a.

Rambam (Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Ishut 8:4) may have had a different Talmudic girsa, because he describes the former as שֶׁאֲנִי יוֹדֵעַ לִקְרוֹת and the latter as שֶׁאֲנִי קוֹרֵא. The Tur (Even HaEzer 38) has our korei/kara’a distinction. Rav Yosef Karo in his Beit Yosef commentary (ad loc.) quotes our Gemara like the Tur, but in Shulchan Aruch (ad loc.) splits the difference, with שֶׁאֲנִי יוֹדֵעַ לִקְרוֹת as the former and קָרָאָהּ as the latter. Perhaps we should consider that vows follow human language, leshon benei adam, and the Hebrew language might have shifted over time. When expressing a condition to betrothal, the fulfillment should follow its present-day meaning. I also wonder whether the prevalence in the Rambam’s day of the Karaites, who rejected Oral Law, influenced his omission of kara’a.

I like our korei/kara distinction. A קוֹרֵא is one who can read (in shul), just as a shomer is a watcher/one who watches. A קָרָא is a more intense level of knowledge, like a חַמַּר or גַּמַּל, a professional donkey/camel driver. Consider the next contrast in the Gemara, תָּנֵינָא, I study, vs. תַּנָּא אֲנָא, who must be a real expert in rabbinic literature.

I’m not sure if this indicated mere literacy or was someone who could lein (chant the parsha). After all, the brayta mentions three verses (a minimum aliyah length) and the shul, plus the Targum which was recited publicly in Chazal’s time after each Hebrew verse. See Aruch Hashulchan (ad loc.) that nowadays that we don’t recite Targum, Targum isn’t required, but leining with trup (cantillation) is necessary. Regardless, we should consider the skills required to accomplish such a reading. Setting aside the Talmudic Narrator, we could understand Rabbi Yehuda’s Targum requirement that he actually knows what he’s saying, and isn’t simply able to sound out the words.

Reading Hebrew Is Hard

Reading from the Torah is difficult. While there are paragraph breaks in the form of petuchot and setumot, (openings and closings) there are no periods to indicate sentence boundaries. There are no markers of phrase boundaries (commas or dashes) either. What is written is entirely consonantal. Yes, heh, vav and yud sometimes occur to indicate the presence of ambiguous vowels, but the text lacks vowel points. If the trup is necessary when reading, it also isn’t written down. Now, you might say that we can read/prepare beforehand from a Chumash which has some of these. However, as Shadal proves in his Vikuach al Chochmat HaKabbalah,2 the written signs for vowels and cantillation are post-Talmudic. One requires a teacher and/or a good sense of puzzling out the likely meaning to be able to produce the correct reading and meaning (translation) in real time. Perhaps these were the skills referenced by the brayta.

In response to a previous article (“Befanay Nechtav”), a reader, Ze’ev Atlas, wrote in to stress the importance of knowing the Hebrew language, arguing that yeshivas should have a regular weekly class in Hebrew language and grammar even at the expense of yet another hour of Gemara. Otherwise, you’ll have rabbis and yeshiva students misreading the Chatam Sofer’s use of גומא to mean גֹּמֶא, a hole in the ground, rather than גֻּמָּא, papyrus.

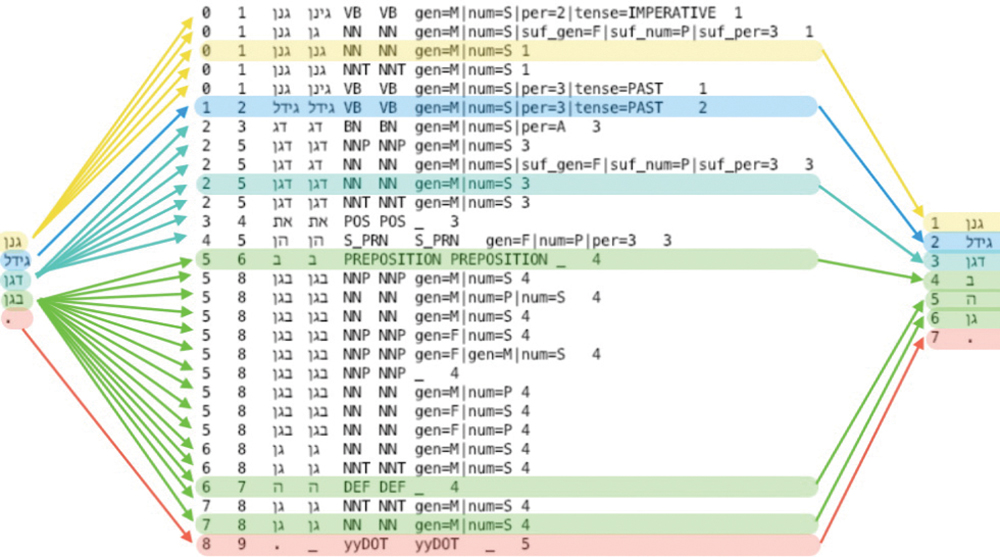

Hebrew language classes are important, though they might not solve this particular problem. As the authors of the YAP parser describe in their article “What’s Wrong with Hebrew NLP? And How to Make it Right,” unvocalized Hebrew is highly ambiguous. The word הקפה can mean orbit, the coffee or her perimeter. In English, you read a word, know what it means, then proceed to the grammatical structure of the sentence. In Hebrew NLP, a pipeline model doesn’t work, because you may need to go back and reevaluate once you encounter other words in the sentence.

To work through an example: I thought דגן meant “grain”; now I see that means their “fish.” (For Talmud: Oops, this was an Aramaic word, the daled was a prefix, and דְּגַן means “of the garden” or “of the garden of.”) The Nakdan website gives eight possible vowel patterns for דגן.

Similarly, בצלך could mean “in your shade” or “your onion.” And, this is true for multiple words in the sentence, with exponential possibilities. Does a prefix ב mean “in” or “in the”? I can’t tell because the patach or sheva (vowel sign) is absent. Is the letter part of the root or morphology? There’s so much extra mental effort in guessing vowels from context, and backtracking when encountering new evidence.

Within his responsa, the Chatam Sofer refers to תיבת גומא כמו נח, חופר גומא, שהיתירו לעשות גומא, and ואין גומא בלא שערות. In each case, the context primes us to think of papyrus, hole or follicle. However, some contexts aren’t so clear, and in halachic literature, the “hole” meaning is the most frequent. Native Hebrew speakers would quickly mentally correct themselves as they scan the sentence, picking up other cues. However, an American who knows some Hebrew, and even knows Noach’s teiva, (ark) won’t necessarily tap into that meaning on the first read, and won’t reevaluate, especially if put on the spot.

English does have such ambiguities, in terms of part-of-speech. Is the word “judge” a noun or a verb? So called “garden-path sentences” take you along one path, then cause you to stop and retrace your steps. For instance, “The old man the boat.” You first assume that “old” is an adjective and “man” is a noun, but then realize that old people are manning the boat. Other examples are “The complex houses married and single soldiers and their families” and “The horse raced past the barn fell.” In our very own Jewish Link, the headline “Shaked Heads United Right” made me shake my own head until I realized it referred to Ayelet Shaked. But these occurrences are uncommon.

Talmudic Struggles

Reading the Talmud is often even more difficult, because of compounded ambiguities. Yes, it lacks vowels. It’s also exceptionally concise, so phrase and sentence boundaries are unclear. It switches between questions, answers and statements, with no question marks, exclamation marks or periods to distinguish. There is frequent code-switching between Mishnaic Hebrew, biblical Hebrew, and Babylonian Aramaic, allowing for the vowel ambiguities of three different languages, their inflections and their affixes.

Native Israelis are surrounded by the spoken word and quickly transition to unvocalized texts. Americans who lack this immersion and who encounter these sophisticated Aramaic/Hebrew texts later in life could consider regularly using a Steinsaltz Gemara to develop a sense of the correct vocalization and punctuation, and cues for ending a statement or switching between languages.

Further, we can identify sources of ambiguity and teach targeted strategies to address them. For instance, when tutoring Gemara, I’ve made worksheets with unvocalized, unpunctuated Talmudic text, alongside the English translation, with the task of applying punctuation or nekudot. Students should learn textual features which indicate phrase/sentence boundaries. What prefixes, such as vav or daled, indicate a phrase boundary or phrase continuation? What prefixes, such as shin or daled, indicate a shift to Hebrew or Aramaic? What words start questions or answers? What are the common pitfalls? Following Kiddushin 29a, we can teach our children to swim, rather than sink, in the yam haTalmud.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 So all manuscripts. Missing in printings.

2 See http://parsha.blogspot.com/2007/12/shemot-vikuach-al-chochmat-hakabbalah.html

3 See https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.05453

4 https://nakdanlive.dicta.org.il/