Dad was born and raised in a small coal-mining town in Pennsylvania. Olyphant had no more than a population of 10,000 in its heyday, mainly Polish and Ukrainian miners, and their industrious families. He was the only Jewish kid in his class.

His father, Harry, prided himself on being a “peddler,” taking his wares door to door in the more remote, even smaller towns that surrounded Olyphant. He always referred to himself as an “American by choice” compared to his children, who being born in this country, were merely “American by chance.” My Zayde Harry cherished his adopted country and all that it stood for.

Dad would watch haircuts at Shifrankos and wander past the store on Lackawanna Avenue. As a young child during World War II, Dad once explained: “We did knitting for an Afghan which was to be sent to an army base, collected flattened tin cans for the war effort, and put all the money we could scrape together into United States Savings Bonds. I wrote daily airmail letters to a cousin serving in the Pacific and followed with close attention how the Allies, the forces of good in the world, battled the forces of evil. Just like the cowboy movies we watched, we knew who wore the white hats.”

He was told early on by his father that his dry goods business held no future, and that he would pay for all the education needed so that Dad could build his own American Dream. My Uncle Jerry attended St. Thomas Aquinas University in nearby Scranton and went off to medical school in Chicago. When Dad expressed an interest in studying religious subjects at Yeshiva University in New York, he had his family’s highest blessings. YU was a transformative experience where Dad became the poster student for Torah Umada, the emblematic blend of Torah scholarship and professional success.

Studying at Yeshiva University broadened his horizons considerably, yet reinforced Olyphant’s values. Even though among young New Yorkers, he considered himself less than sophisticated; the university was dedicated to proving that traditional religious and moral values were very much at home in the American environment.

Later in life, believing in the great American adventure and its system of justice, Harry urged my dad to follow his interests in law—despite a lack of funds. He eventually went back for a degree in corporate law at the NYU Graduate School of Law’s evening program.

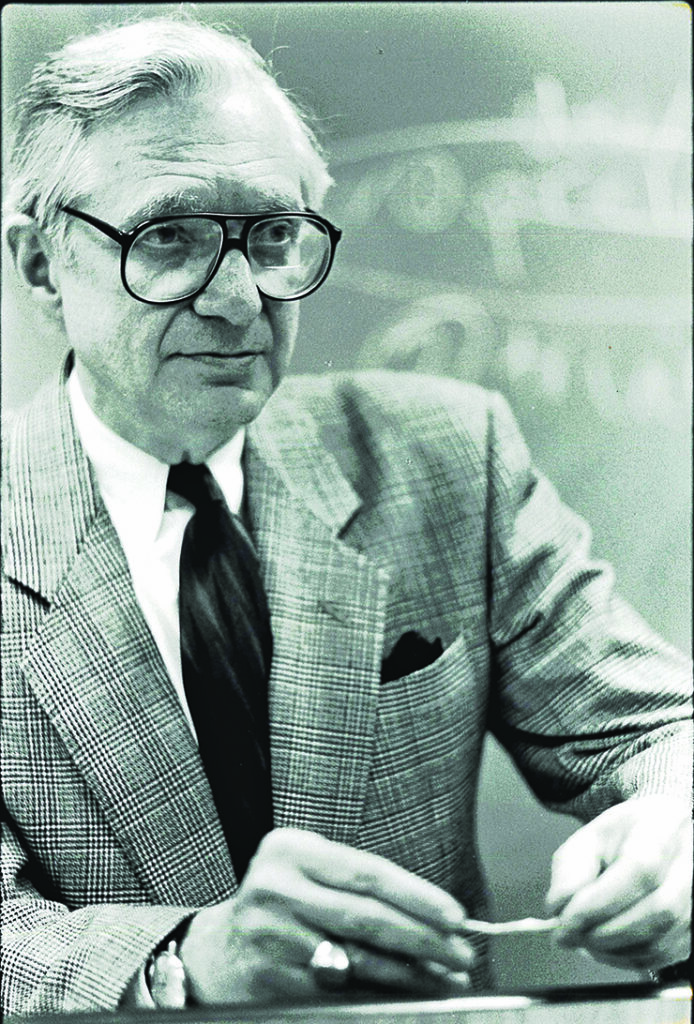

At the time, Professor Elmer Fried taught the only available course on immigration law—not just at NYU, but in the whole country. No other law school had such a class. The course description fascinated Dad, who once wrote: “Some of the people who needed the help of an immigration lawyer were the most disadvantaged in society, and such a lawyer’s assistance came at the very moment of their greatest need.”

Dad’s first job as an immigration lawyer was with HIAS, the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society. He knew the organization not only helped Jewish people to migrate but also taught these newcomers the American way. The notice sought an attorney with fluency in either Yiddish or Hebrew. It was at that time that he wrote an article intended for publication in The New York Law Journal, which accepted his handwritten manuscript. The article apparently filled an important need in the legal community and made some valid suggestions for the Immigration Bar. Edith Lowenstein, the editor of Interpreter Releases, the most important publication in the immigration field, asked for permission to republish the article. Dad also then learned it was then going to be used as a text for a six-week course given to future visa officers.

Fried suggested that he open his own office. During the summer of 1960, he was retained by the parents of two young men who had lost their American citizenship while abroad. They had gone to help establish a Jewish homeland when the State of Israel was founded. When they failed to respond to notices sent by their American draft boards in the early 1950s, they were considered delinquents. Dad traveled to Israel for an eight-week journey, ultimately winning his case in Washington before the Passport Review Board. He was offered a job as an attorney with the staff at the State Department.

In the end, the rest is history. Dad stuck with his practice and in a few short years, managed to save enough money to afford a real office. Two years later he married Mom, and together they built up a small reputation with diligent work and successful outcomes for his clients. His article on visa denials also resulted in a good number of referrals from other attorneys, who graciously referred to him their “impossible” cases. Through extraordinary effort, he was uniformly successful in the cases given to him by clients and in turn they referred relatives and friends who needed help.

When Fried, his former immigration law professor and progenitor of the law firm Fried Fragomen, told Dad that he was looking for office space and asked whether he would be interested in joining him. He jumped at the occasion and called upon another dear friend, David Fund, who was both an accountant and an attorney, to sign a lease at 515 Madison Avenue, where to date Dad’s practice remains headquartered for over six decades.

Having access to Fried, whose knowledge in the immigration field was extraordinary, and to Fund, whose experience in corporate and business matters was unsurpassed—Dad took his practice to a new level. At this point in his career, he was still accepting cases in almost any field of law, but felt privileged in handling immigration matters for clients, their relatives, employers, friends and acquaintances. That was the most gratifying of all his legal efforts. Assisting a person to regularize their immigration status and get started on life in a new country is the most rewarding kind of work one can imagine. Many of his clients became employers themselves, and in turn sponsored other non-citizens. Corporations, banks and industrial concerns sought out his legal counsel and services based upon their favorable experience in sponsoring one of the firm’s clients.

Dad began to hire young attorneys, paralegals and other staff, always with some trepidation when it involved increasing the costs of running the office, but always seeking out the best and brightest people that he could find to assist in his work.

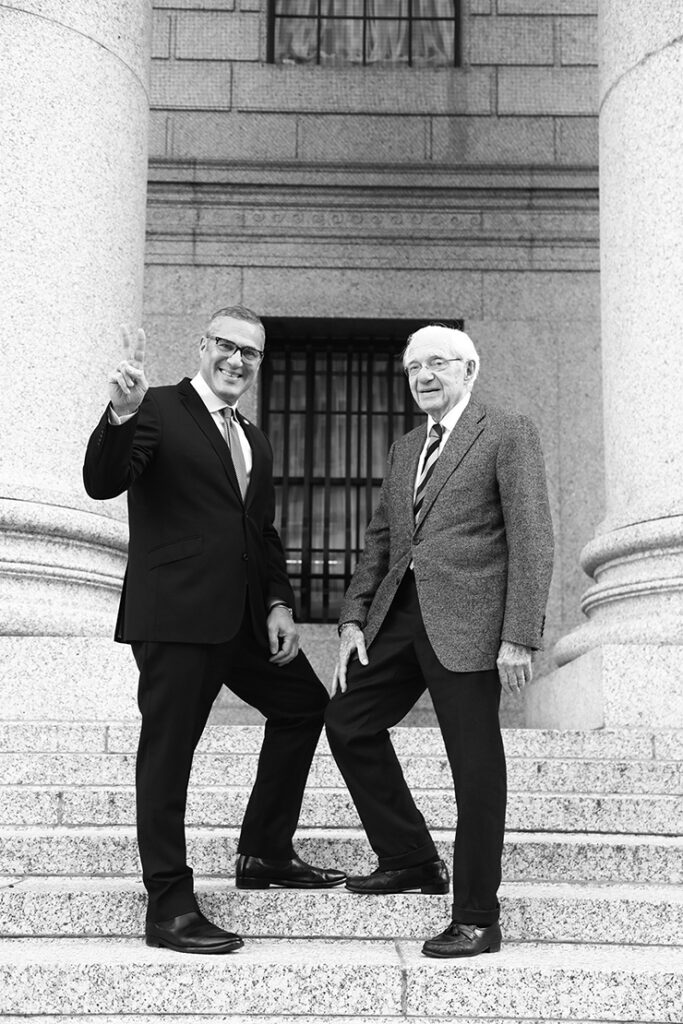

In 1976 he formed a partnership with Steven Weinberg, a talented immigration lawyer who he later loved as family, and later changed the name of the firm to Wildes & Weinberg. I joined the firm in 1993 and became a partner in 1996. My son Josh joined in 2021.

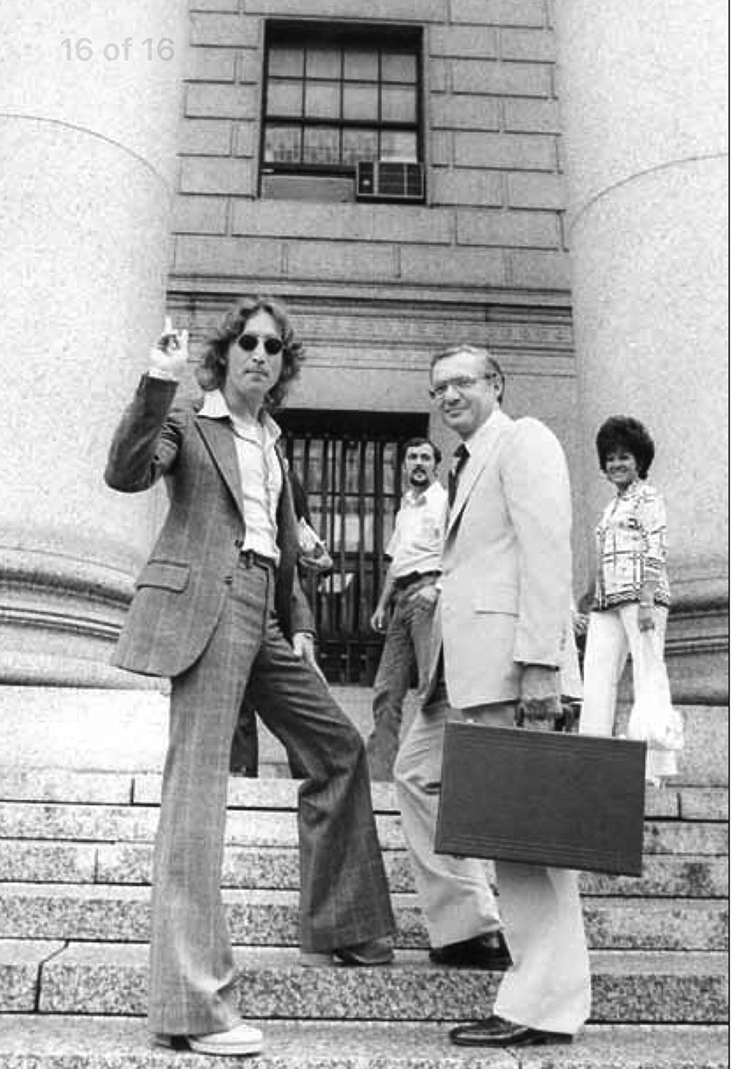

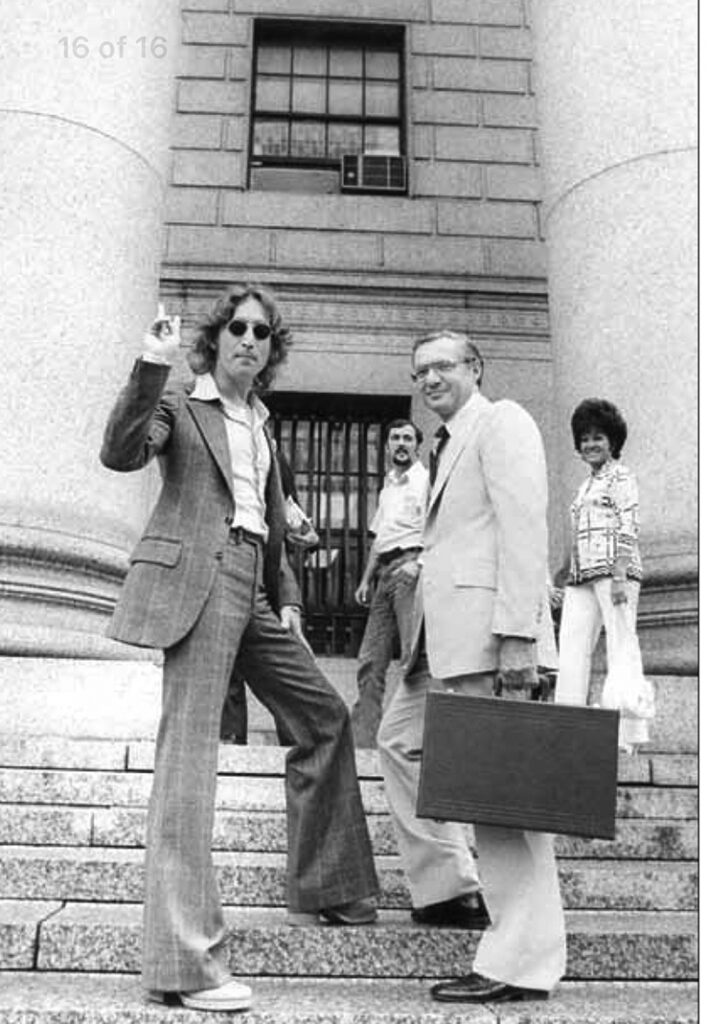

Following the example of Professor Fried, Dad happily accepted the invitation of the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law to teach immigration law, lecturing on the subject for 33 years. In 1970 he was elected the national president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, the bar association in the field. In fact, it was shortly after completing that term in office that he got the call to consult with former Beatle John Lennon and Yoko Ono about their immigration problem.

Dad wrote: “I think I can say that my career pretty well fit the daydream of an All-American success story for a kid from Olyphant. With this case, though, I found myself defending not just John and Yoko’s personal dreams, but the foundation of the American Dream itself.”

I remember Harry’s funeral like it was yesterday. Dad compared him to a compass, a small instrument capable of steering tonnage in the right path. At my mother Ruth’s funeral 28 years ago, Dad eloquently cited and wove Bette Midler’s song “Wind Beneath My Wings” into our mother’s exuberant love of family and robust charm.

If I had to coin my father in a few words, it would be his professionalism, modesty and propriety. I knew damn well as a kid that the law firm was my older brother and if I wanted to spend time with Dad, I would have to dig in. My earliest memories are cutting scrap paper on Sundays and making lists of things he had to do as we drove to work together.

My brother and I noticed that our dad spoke with the same keel to our mother as he did to our clients, rock stars, prime ministers and staff in our office. “Ruth in a booth on Line 7” would ring out from the receptionist, and with that code, dad would take every call from my mother, as urgently as he would a new legal matter. He dressed elegantly and waited until everyone else had spoken before he offered an opinion, often crediting others for his own achievements.

His punctuality would drive us crazy, often walking out to shul while my brother was just jumping into the shower! I would show up to funerals with Dad often wondering if the person had really died!

Our formative years in Forest Hills and at the Queens Jewish Center were impactful. Dad served two terms as president of a shul whose shovel was put into the ground by his father-in-law Max Schoenwalter. He regaled the elegance of his in-laws, the Schoenwalters—my German grandparents—with great respect and pride, inviting me to this legacy when he gifted me Max’s prized cufflinks.

He was a scholar who taught hundreds of future lawyers, prosecutors, judges and jurists. He would inspire careers and toil for people to achieve the Holy Grail of U.S. permanent residence or citizenship. I take up some of Dad’s landmark precedent cases as I had the good fortune to succeed him in teaching at Cardozo for the last 13 years. (Matter of Hira, etc.). I met my beloved wife, Amy, in his class, and had the good fortune to teach two of our children and son-in-law, while their Zayde annually guest-visited and taught the Lennon case.

His most lasting work, on the John Lennon case, was substantial not only in the vindication of a celebrity standing up to political pressures in the 1970s, who used his broad influence to advocate for peace. The key legal elements Dad developed during that case, of prosecutorial discretion and deferred action, also known and taught in law schools as “The Lennon Doctrine,” continue to have a profound impact on the lives of thousands of people today. That precedent was used in 2012 by President Barack Obama when he used his executive powers to establish DACA—or Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals. This allowed hundreds of thousands of immigrants who entered the country illegally as children—who came here through chance, rather than choice, attending our schools, serving in our military, and living as part of our communities—to avoid deportation, gain legal working status, and have a pathway to permanent legal residence in the only home they have ever known. When you hear about “Dreamers,” that is who it refers to, and that is Dad’s perpetual gift to the world. Now numbering well over a million people, they are keeping alive the dreams of so many people to pursue the same opportunities for themselves and their own families that he himself was so fortunate to have, and instilling those values in generations to come.

Now the stuff that really mattered to me: I held his briefcase when we would walk to and from the office. I was benched every Shabbos and then before exams and donning my bulletproof vest as I would drive my parents crazy and walk a beat as an auxiliary police officer. When I flunked the bar exam, he stayed with me in a hotel in Albany to review my performance and enhance my confidence. Dad was an artist who painted, sculpted and drew beautifully. He was ambidextrous and loved poetry and opera. He masterfully reviewed every correspondence, class presentation and speech I ever gave with a red pen. He hugged and kissed his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren on every opportunity he had. He loved peanuts, music, his wives, and shopping like no other. He treated my wife, Amy and my brother Mark’s wife, Jill, as daughters, and they treated him as a father. Picture him and Amy driving three and a half hours to Olyphant while Amy did not stop talking: I may have missed a few words, Dad certainly didn’t. Later in life Amy would create outings and theme dates. She took him on a historic tour of the architectural import of Grand Central Station and to the Hungarian Pastry Shoppe, a quirky café for writers near Columbia University.

A tremendous thank you to Alice, Josie; Ari; Aggie and Shraga and her four beautiful granddaughters Eliana; Chloe; Magnolia; and Geesia—for treating our father as their own and for the respect and dignity they always imbued. He relished Alice’s cooking as she opened his eyes to modern taste and colors. Ari and Shraga would accompany him to shul, his other “happy place” in life.

Dad adored my brother, Mark. He respected his scholarship and couldn’t have been prouder when Mark chose to become a rabbi. We memorialized our late Mom year after year at Manhattan Jewish Experience, a fixture in the lives of so many young Jewish people on this great island. Dad enjoyed painting signs for Mark’s events and meeting young professionals who were in the early stages of their journey—mentoring many of them. But more than that he drew closer in his own personal relationship to God—through his beautiful son the rabbi. Dad was equally impressed with Jill’s chen, charm—and the effective way she added even greater value to the scores of marriages and smachot that emanated from MJE’s efforts.

On Dad’s behalf we want to thank the entire staff of Wildes & Weinberg both past and present. Every one of you has played an instrumental role in the development of Dad’s legend and the legacy we are honoring here today. I will do my best, as will my son, to be worthy of the title “Mr. Wildes” each day. If you haven’t already, please take the time to watch the “Leon Wildes Legacy video” on our website: https://www.wildeslaw.com.

Mark and I had the honor of helping Dad with the Viduy prayer, wondering afterwards what, if anything, he could have ever done wrong. I ask forgiveness, mechila, if I ever offended you, Dad, or preempted you in any way. Mark and I now have the best advocates by Hashem’s side—for our children and grandchildren.

I’d like to thank my children for all they did to remember their Mima and for the kindness shown to their Zayde. Giving up your bed, traveling, and inviting him into your lives together with your spouses and children. To my nephews and niece: I know how proud he was of all your achievements and have no doubt he will catch my mother up on what she has missed all these years.

To Dad’s older brother, my Uncle Jerry, who is virtually joining us from Israel: He so cherished your recent visit as he always loved and respected your success and family.

Special thank you to Muriel, Otar, Alex; and Rabbi Rudensky at the Jewish Home Hospice Care, who never let the wheelchair matter and treated him with dignity.

Ladies and gentlemen: How can I sum up the work and life of a renaissance man? When I think of my dad, the most relevant biblical leader who comes to mind is Moshe Rabbenu—known for his humility, wisdom and golden presence. Dad taught us by a similar example: how to work, live and raise a family. Let us all honor his legacy by doing the same.

I love you, Dad. Rest in Peace, Sir.

Michael Wildes is the mayor of Englewood, New Jersey and the author of “Safe Haven in America: Battles to Open the Golden Door.” He is a former federal prosecutor and an adjunct professor of immigration law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law.