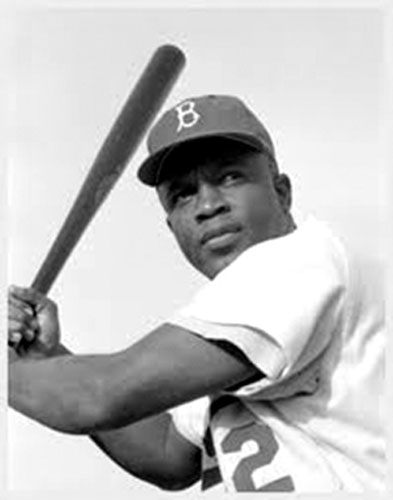

.jpg) Jackie was the first. Jackie could not just play the game for himself. He was playing the game for every one of his race who had been denied a chance, whose future was closed because of racism and segregation. Indeed, as I remember it, Jackie played the game for every minority kid whose opportunities were constrained because of discrimination.

Jackie was the first. Jackie could not just play the game for himself. He was playing the game for every one of his race who had been denied a chance, whose future was closed because of racism and segregation. Indeed, as I remember it, Jackie played the game for every minority kid whose opportunities were constrained because of discrimination.

I was but a toddler when Jackie broke in. My mother was often ill and my father, a decorated World War II veteran, was struggling to make up for lost time in the post-war years. He was 35 in 1945, the year the war ended, 35 and just beginning his career which was delayed by the Great War and the Depression. In a frenzy to make something of his interrupted life, he worked all hours of the day and night. So we had an African-American cleaning lady, Minnie—an intelligent stately woman who in our era would have gone to school and become a professional, but in those days merely struggled to survive.

Minnie loved me and she loved the Dodgers and the Dodger she most loved was Jackie. On his shoulders went the fate of all those denied an opportunity, and the destiny of all, those such as my father, who were to struggle to make their way in the post World War II world. He loved Jackie as well and their love for Robinson was race blind—he was the great equalizer between men, women and children of diverse races and creeds.

Fire, passion, daring, Jackie was anything but a simple athlete. He fought every day and every moment of every day. He was the forerunner of the civil rights movement of the 60s, and the struggles for equality that were to follow. He would do anything to win. And when finally he was freed from his vow of silence, he played baseball with intensity unmatched in the history of the game. He could beat you with his bat, with his glove, with his base-running, and even with his mouth.

Duke Snider recalled a game in which Robinson tormented the pitcher until he was hit by the pitch. He then took a huge lead off first base and challenged the pitcher to pick him off. The throw to first was wild and Robinson took two bases. He then threatened to steal home, until the unnerved hurler threw a wild pitch. Robinson lumbered home, staring at the pitcher.

Robinson was determined to overcome the weight of centuries. My father and Minnie understood his struggle. Orthodox Jew and underprivileged black, they both saw in his daily battle a mirror of their own lives and the hope for future generations. If he made it, they could; if not them, then their children.

Pee Wee Reese was the Dodger Captain. Kentucky bred and almost a decade older than his teammates, he had broken into the game before World War II and was a star before his career was postponed by wartime duties. Reese was stable and able, dependable, savvy and smart. One could sense his roots in his demeanor, his pronunciation of his words, his courtliness, southern grace, and courtesy. So when Reese answered for Robinson, America took note. When he braved the taunts of fans and the displeasure of his southern friends by embracing Robinson as a teammate, as part of his double play combination, Reese came to exemplify every southerner who was willing to make segregation a thing of the past. There were a few such ball players in 1947, too few then, too few now. Several Dodgers protested Robinson’s arrival. One year later Rickey traded them. He was determined to integrate baseball and willing to pay the price.

Roy Campanella, certainly not the least of his mates, was all heart. One experienced the joy of the game, his love of baseball, in his every move. Stocky and compact, Campy would be surprisingly swift on the base path and a stonewall protecting the plate. He was talkative. Campy would kibbitz with the batters and the umpires. He was as masterful at banter as at handling pitchers, speaking to them not just with his mouth, but by pounding his fists, gesturing in every direction.

The man loved what he did, and did it so well. Three times he was the National League’s Most Valuable Player, the most valuable of a most impressive team, and when Campy played well, the Dodgers would win.

Campanella was formed by his experience in the Negro Leagues. Prior to being signed by the Dodgers, Campy played baseball year round. He reported to the Negro Leagues each spring and summer and went down to Venezuela to play ball in the winter. His alternatives were few. With a bat in his hand, he would club his way to a future. In the Negro Leagues, double headers were routine. Oftentimes teams played in two different cities during the same day. They brought their own lamps and polls to play nighttime baseball in then unlit stadiums. Travel was by bus where players often slept at night, denied entry into hotels in the segregated South and the inhospitable North. Motels were then unknown. Campy began his baseball career at 14, or so he said, for Negro League players often lied about their age in order to convince the white baseball barons to take a chance on their talents. By the time he began his 10 year major league career, Campanella had played professional baseball for 12 long years, summer and winter. Until Robinson was signed, Campanella could not dream of a big league career. He forever remained grateful that he was given his chance—just before it was too late.

Robinson and Campanella represented two faces of race and ethnicity in Brooklyn of the 1950s, then the most ethnically diverse and integrated city in America. For us Jewish boys—and I suspect the Irish and Italians as well—Jackie and Campy were familiar figures. And they were not fond of each other for they each represented the polar opposites as to how to behave as a minority in the larger culture. Their struggles and the tensions between them were part of our family lore.

When our fathers told bold stories about standing up to antisemitism and demanding their rights; when they exploded in anger or triumphed by chutzpa, they became for us mini Jackie Robinsons—strong, and heroic. All over New York, Jews were breaking down barriers by being angry, demanding and insistent—by playing the game more fiercely, with greater daring and conviction than the “white boys.”

When our fathers told us not to make waves, to be grateful for how far we had come, to remember with gratitude the opportunities we had been afforded, we thought of Roy Campanella. He knew what would have been his fate had he been given less talent, had opportunity not come his way just in time. Ever thankful, he could not be angry.

First generation Jews, Italians, and Irish and other ethnics understood Campy. The talented sons of pushcart peddlers and small merchants, of factory workers and machinists, were attending Harvard or Yale and even grateful to be at City College. And in those days Jews who went to the Ivy Leagues soon assimilated—and if they did not, they were reluctant to go public with the identity they held sacred in private.

In my New York Yeshiva, we were taught that a yarmulke was an indoor garment. Hats were to be worn in the street. In the 50s, Philip Roth was writing about Eli the Fanatic, the fearsome Jew who practiced his piety in public and embarrassed his assimilating neighbors.

So while my father and Minnie rooted for Jackie; more often than not, they played the racial and ethnic game like Campy. Jackie was respected, Campy was loved.

Michael Berenbaum Reprinted with permission from The LA Jewish Journal