It was a shot in the dark, literally.

My weekend trip to Amsterdam was already planned, an exciting opportunity to join my father for a few days on the front end of a business trip, biking around the canals, checking out the famous tulips and walking through a bit of Jewish history from a once thriving community.

But our trip suddenly took on deeper, personal meaning with the discovery of a postcard just a few weeks before that possibly revealed my great-grandmother’s hiding place during World War II.

Many of us hear Amsterdam and think of Anne Frank, a young teenager hidden with her family in a secret annex who was ultimately found and killed by the Nazis. My great-grandmother Clare Teig had a similar story, when in 1938, as a young girl of 11, she was sent by her parents with her 14-year-old brother Richard on a kindertransport train from Essen, Germany to escape the rise of Jewish hate and restrictions on daily life being imposed.

Upon reaching the central train station in Amsterdam, they were adopted by a middle-age couple, who were among many Dutch families who answered the call from German Jews desperate to get their children to a safer place.

Great-Grandma Clare’s story of survival does not actually take place in Amsterdam, but rather in The Hague, which is Holland’s third largest city about 40 miles southwest and where she lived with the Drielsmas for nearly eight years. For the first few years, between 1938-1940, Clare tried to live a semi-normal life, going to school and helping with chores while her brother Richard worked in town to support the household.

But Germany’s occupation of Holland in May 1940 changed their fate suddenly. Richard was taken by the Nazis to work in the Westerbork transit camp in northeast Holland, leaving Clare to go into deep hiding with the Drielsmas in The Hague.

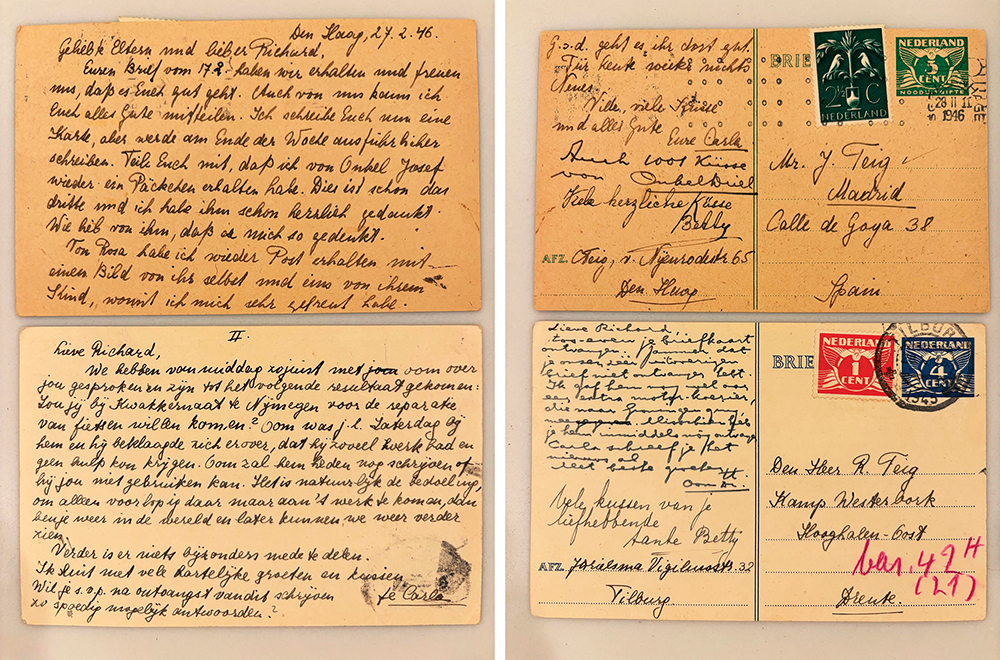

For five years, the two siblings did not know if the other was alive. After the Nazis surrendered in 1945 and withdrew from Holland, Richard sent the Drielsmas a postcard inquiring of his sister’s fate and sharing the fortune of his own. Betty Drielsma wrote back to Richard with a certain vagueness that everyone was doing fine, apparently still scared that too much information could leave Clare vulnerable to Nazi sympathizers.

The postcard was found recently in my great-uncle’s belongings after his passing last year at age 96. It wasn’t what was written on the back that was so important, but rather the return address on the front: 65 Van Nijenrodestraat, Den Hague.

Great-Grandma Clare passed away at age 62 well before I was born. We knew from her limited stories that she lived in an attic bedroom, taking careful steps not to be found since the Nazis had requisitioned many houses in The Hague as their living quarters.

With the postcard in hand, Google Maps on our phones and a couple of rented bicycles in traditional Dutch fashion, we disembarked from the train at The Hague’s central station not knowing if or what we would find.

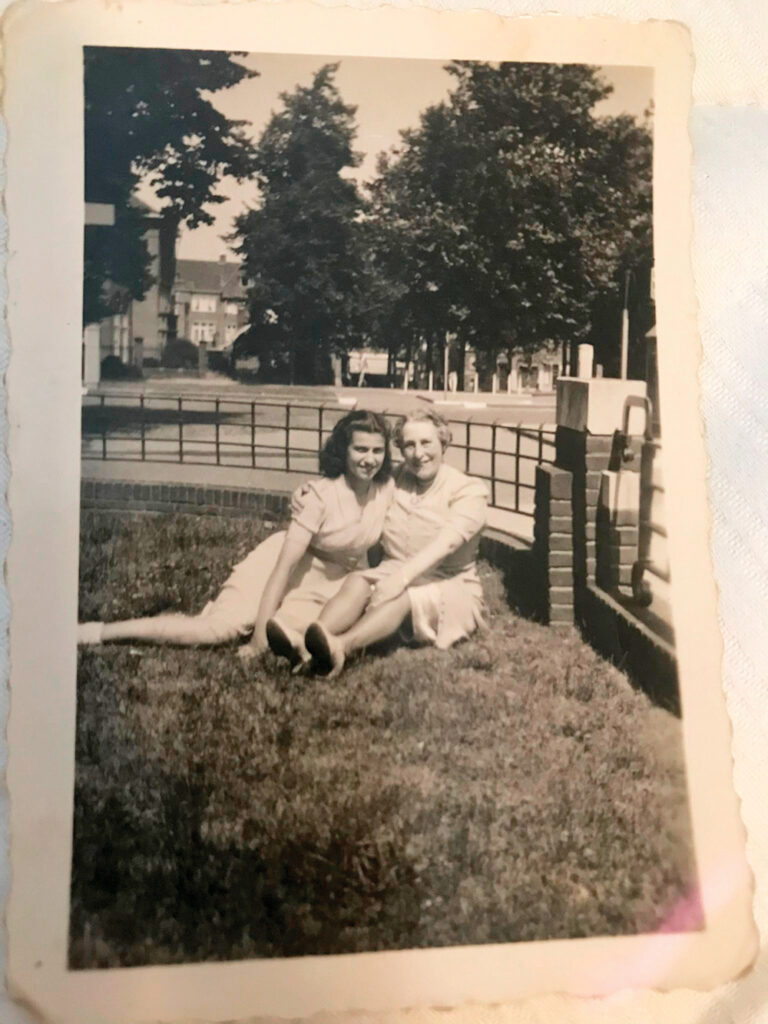

We rode for about 40 minutes through city streets, woody parks and leafy neighborhoods, ultimately arriving at a row of attached houses on Van Nijenrodestraat. The clue that told us we were in the right place was a black-and-white photo of my great-grandmother and Betty Drielsma sitting in a park opposite the row houses, a photograph that remains with our family to this day.

The legend of the picture was that it was taken by a Canadian soldier in the spring of 1945 who was among the Allied forces to liberate The Hague. My great-grandmother, 18 years old at the time, is generously smiling with Tante Betty, as I learned she was called. In front of them is a low brick wall encircling the small park, the same brick wall in front of us now.

My father and I looked at the picture and then again at each other in awe. Yes, we were in the right place. Our eyes scanned the addresses on the row houses and together honed in on number 65. Right in front of us was the exact house where my great-grandmother was hidden. We took deep breaths as we built up the courage to knock on the door, worried that whoever might answer would think we were crazy and turn us away.

Suddenly, a boy of about 9 or 10 came running up the street to the front door with a confused look on his face. We tried to explain to him who we were but realized it was a hopeless effort and simply asked if his parents were home. I felt a dash of relief when I recognized the boy was speaking English with a British accent.

As the mother appeared at the door, my heart began to beat just a little harder knowing how close we were. We explained our story, showing her the postcard and the picture from the park. We asked if there was an attic that might have been where my great-grandmother was hidden. She said that the attic had already been converted into a bedroom before they moved in, but upon hearing the words “hiding place,” the 9-year-old boy tugged at his mother’s arm and anxiously reminded her about the hiding space underneath the dining room floorboards.

A hiding space beneath the floorboards? My heart raced a little bit faster. At this point, the mother became flanked by two more younger boys and her husband and she invited us inside, leading us through the kitchen to the dining room. We watched suspensefully as the oldest boy got to work, moving a small end table from against the wall, not seeming to care about the knickknacks on top falling down. Underneath the table were loose floorboards that he began to pull up, revealing a small opening into a dark, crawl space underneath.

This must have been her hiding place, I thought, and my heart raced even faster. I peered down as best as I could into the crawl space, and with my father’s encouragement carefully lowered myself into the space. It was fairly large, spanning the length of the house, but I could barely stand without the top of my head grazing against the floor joists above me.

Using the flashlight from my phone to see past the darkness, I saw that the floor was carpeted but riddled with cobwebs and stains. My thoughts were rushing as I suddenly felt a bridge to 80 years past where my great-grandmother must have spent terrifying hours, days and weeks when it wasn’t safe to be in the house or even in the attic.

I tried to imagine what it would have felt like to be rushed into the crawl space without warning when Nazis were patrolling the streets or conducting house to house searches for Jews. The intensity of the moment was surreal crawling beneath the same floors that my great-grandmother did all those years ago. I noticed a string hanging down from a lightbulb and pulled it, but the crawl space remained dark. I hoped that Grandma Clare at least had some light by which to read during the long hours she must have spent down here.

I slowly climbed back up the ladder to the dining room, powdered in dust, dirt and spider webs. I couldn’t shake the sensation of little critters crawling down my neck, but in a strange way I did not want to. I wanted to know what Grandma Clare must have felt.

My father and I thanked the family for inviting us into their house and rode back the same way we came, wrapped in disbelief over what we had found. My great-grandmother’s hiding place, once lost to history, was rediscovered using the front of a recently found postcard that was preserved unknown to anyone for almost 80 years.

After the war, Grandma Clare and Uncle Richard reunited and, even more surprisingly, learned that their own parents had survived the labor camps where they were interned in southern France. Eventually they reunited in Spain and together were sponsored for visas to the U.S. in 1948.

We know that soon the generation of Holocaust survivors will no longer be with us and I feel incredibly fortunate to have had this experience as a way of passing on at least one of their stories.

Atara Siesser is a graduating senior from Ma’ayanot and planning to spend next year at Aish Seminary in Jerusalem.