In Bava Batra 47b, we encounter the “Sicarius,” in a quote from Mishnah Gittin 5:6. That Mishna lays out a law that, if one first purchased land from a Sicarius (who extorted the field from its prior owner with threats) and subsequently purchased the same from the original owner, the sale does not work. However, in the reverse order, first from the owner and then from the Sicarius, the sale works. As that Mishnah explains in Gittin 55b, this is akin to first acquiring from a husband the rights to use a field belonging to the wife, then buying the field from the wife, where the purchase is void, but in the reverse order, it works. This law of the Sicarius was revised by a later court and again by Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s court. The Gemara there discusses the historical background leading to these decrees.

In our sugya in Bava Batra, the Talmudic Narrator uses that Mishna to question the novelty of Rav Huna’s ruling. For Rav Nachman (bar Yaakov) said that second-generation (Rav) Huna told him that if a robber (gazlan) who presented proof that a field is his, that proof is unacceptable and the court doesn’t place the field in his possession. The underlying idea is of concern that the proof was obtained illegitimately. That seems to echo the Sicarius case.

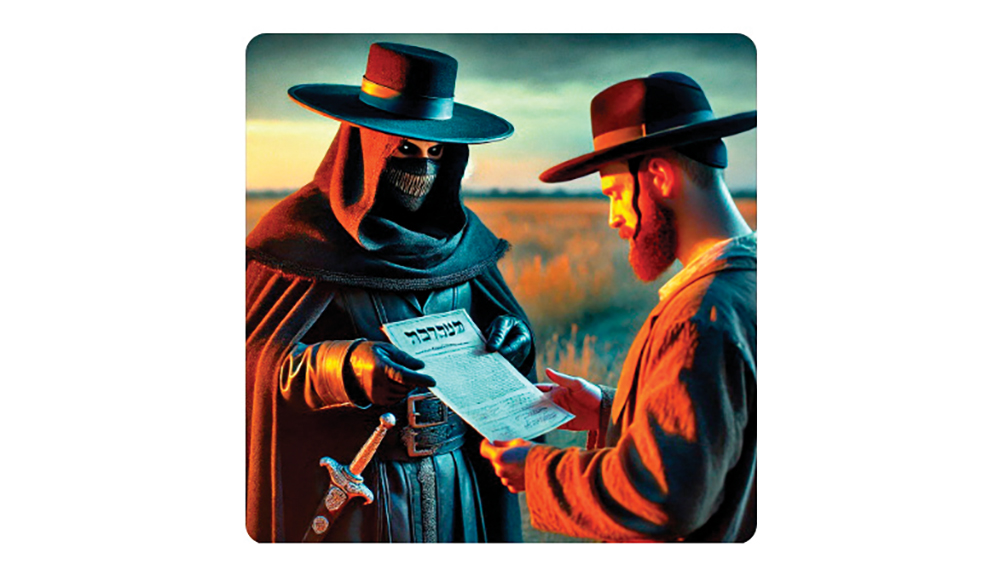

The Narrator answers that the novelty is that Rav Huna disagrees with Rav, who doesn’t void the Sicario sale if a shtar (deed) was written (see image), and sides with Shmuel who only doesn’t void it if they wrote a property guarantee.

This resolution surprised me in two ways. First, the Gemara’s general assumption is that Rav Huna must always echo his teacher Rav. See Bava Kamma 115a, הָא רַב הוּנָא תַּלְמִידֵיהּ דְּרַב הֲוָה, and my exploration of the idea in a Jewish Link article, “Rav Huna and Rav Must Agree” (Feb 22, 2024). Second, is a ganav really akin to a Sicarius? I’m operating under the (mis)impression that a Sicarius is a lot scarier than a robber. The word derives from Latin sica, a dagger, and means assassin / hitman. See the Spanish word Sicario. It was also the name of a Jewish sect of assassins during the period of the Great Revolt, as Josephus describes.

A gazlan who steals in general might be suspected to have used improper pressure to force the original sale, but a hitman might cast fear even after the fact, if someone later contests the sale.. A court-imposed restriction on a hitman might conceivably not apply to a mere robber.

Yet, two sources may work to conflate a Sicarius and a robber. The Mishna in Bikkurim 1:2 states that a sharecropper, leaser, Sicarius (one who occupies confiscated land) and robber (gazlan) don’t bring first fruits from that land, because the verse states one should bring the first fruits of “your” land, and it’s not really theirs. Bikkurim 2:3 restates this, to make a distinction between first fruits and terumah and maaser sheni. We might wonder if that’s enough to equate them in other contexts. Mishnah Machshirin 1:6 first discusses one who hid his fruits in water because of גַּנָּבִים, then describes an incident in which the men of Yerushalayim hid their pressed fig cake in water because of the סִיקָרִין, murderers / robbers / Sicarii, and despite this placement, the Sages declared that that doesn’t render them susceptible to ritual impurity. However, the word is slightly different, lacking the second kuf – though Rav Hai Gaon does have a reading of סִיקָרִיקוֹן – so perhaps it’s a different word.

Defining a Sicarius

My second objection may be based on a misimpression. What, really, is a סִיקָרִיקוֹן? Rav Adin Steinsaltz first gives the etymology above, then explains that there’s “a difference between the Sicarii in the Talmud and the faction of the Sikarikim, an extremist faction in existence during the period of the Great Revolt,who were given this pejorative name by their detractors.

The [Talmudic] Sicarii included different types of people, among them soldiers discharged from the Roman army, other gentiles who acted as the occupying force and various Jewish collaborators. Through threats and extortion they bought properties or received them as gifts. The properties were acquired by ostensibly legal means, such as, deeds of sale and the like.

Most of the Sicarii were not interested in maintaining these properties but rather sought to profit from them. For this reason, after they seized the properties they would sell them to the locals, both Jews and gentiles. Since the Sicarii secured these properties for almost nothing and had no interest in maintaining them, they would sell them at rates far below their market value.”

This is an excellent definition, which helps us understand why someone is willing to buy twice, once from the Sicarius and then from the original owner, as well as why the sale might lack validity. By noting the distinction of the Talmudic term from the Judean faction, Rabbi Steinsaltz preempts the confusion that may arise.

The Aruch and others give the following definition: סקריקון ממונה להרוג נפשות וכשבא להורגו אומר לו שא קרקעי והניחני. Thus, he’s a hitman, but when he comes to kill him, he tells him to take my land and leave me alone. This notrikon etymology is descriptive of one definition of the term, but presumably the true etymology of the word should be from a foreign language, much like henpek and apotiki. Jastrow, meanwhile, distinguishes between סִיקָרִין (as in Mishna Machshirin above), which are Sicarii, and סִיקָרִיקוֹן with the second kuf, which is “a disguise of [Greek] καισαρίκιον,” which stems from the Latin word caesaricium, meaning property confiscated by the Roman government. Essentially, we are dealing with land the Roman government allowed its citizens to seize from Jews who were absent, killed or captured, or which the government had confiscated under laws of ager publicus, public land expropriated by Rome’s enemies.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.