וַיֹּאמְרוּ אֵלָיו אַיֵּה שָׂרָה אִשְׁתֶּךָ וַיֹּאמֶר הִנֵּה בָאֹהֶל. (בראשית יח:ט)

“And they (the angels) said to him (Avraham), ‘Where is Sarah your wife?’ And he said, “Behold! She is in the tent.””

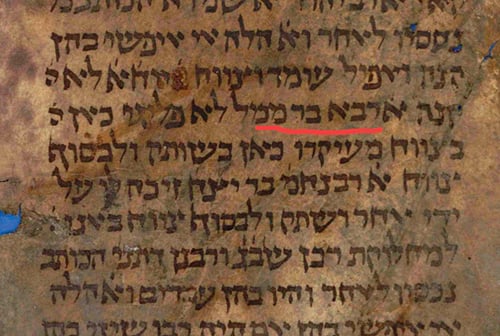

In Gemara Bava Metzia (87A), there are two opinions why the malachim asked Avraham where Sarah was. The first opinion states that the malachim genuinely didn’t know her location, and the Torah includes this detail only to highlight Sarah’s modesty. The second opinion—attributed to Rav Yehudah, in the name of Rav (and some say in the name of Rabbi Yitzchak)—suggests that the malachim knew Sarah was in the tent, but asked where she was to make Avraham recognize her modesty, thereby strengthening their marital bond (Maharsha).

Zera Shimshon raises questions on both opinions:

Regarding the first opinion, Zera Shimshon asks why the Torah finds it necessary to specifically point out Sarah’s modesty, when she is already known to be a righteous and virtuous woman. Sarah is known for her righteousness, which is a comprehensive term encompassing various virtues. Why does the Torah feel the need to single out her modesty? Mentioning it separately seems redundant and unnecessary!

Regarding the second opinion, that the malachim asked her whereabouts to strengthen their marital bond, Zera Shimshon directs our attention to the beginning of parshas Lech Lecha. In that portion—as Avraham and Sarah are nearing Mitzrayim after leaving Eretz Yisroel—the pasuk notes that Avraham suddenly becomes aware of Sarah’s beauty. Rashi explains that this awareness came about because they were both modest individuals. Considering this, Zera Shimshon questions the need for the malachim to highlight Sarah’s modesty to Avraham, given that he was already aware of it.

Zera Shimshon addresses the second question by referencing the Gemara in Shabbos (53B), which recounts an incident of a man who discovered his wife had a stumped hand only upon her death. The presence of two opinions in the Gemara—attributing the modesty either to the wife or the husband—suggests that the modest behavior was actually the result of a combined effort between the two. The dispute is only as to who should be credited as the primary driver of this exceptional modesty, the husband or the wife.

According to this, the fact that Avraham was unaware of Sarah’s beauty for so long doesn’t necessarily serve as definitive proof of Sarah’s extraordinary modesty. Instead, it could be the result of a shared sense of modesty between Avraham and Sarah that contributed to their mutual unawareness of each other’s physical attributes. In this context, the malachim’s question about Sarah’s whereabouts served a specific purpose: it was intended to clarify for Avraham that Sarah’s modesty was, indeed, her own unique and remarkable trait—separate from any mutual modesty they may have shared as a couple.

Regarding the first question, why did the Torah have to teach us that Sarah was modest since we know that she is very righteous? Zera Shimshon explains that the main goal of a woman’s modesty goes beyond personal virtue; it serves as a form of chesed that has far-reaching effects on the spiritual well-being of klal Yisroel as a whole. By acting modestly, a woman engages in a profound act of self-sacrifice and kindness—directly assisting men in their ongoing struggle with their powerful yetzer hara.

This is not a small feat. The yetzer hara is a very strong, difficult and formidable force, constantly tempting individuals to stray from the path of Torah and mitzvos. In this context, a woman’s modesty becomes an invaluable asset in the communal effort to live a life of kedusha. Her modesty acts as a safeguard, helping to reduce distractions and temptations that men might otherwise find difficult to ignore. It’s a proactive form of chesed that requires thoughtfulness, intention and often self-sacrifice, as it involves curating one’s behavior and presentation in a way that prioritizes the spiritual welfare of others.

Therefore, a woman’s modesty is not just about her own spiritual elevation, but also serves as an act of significant chesed to others. It’s a contribution to the collective spiritual integrity and focus of the community, helping men to better maintain their concentration on learning Torah and the fulfillment of mitzvos. By acting modestly, a woman effectively supports the spiritual framework of the entire community—aiding in the battle against the yetzer hara and promoting a society deeply rooted in kedusha.

On the pasuk (18:5), “And I (Avraham) will take (for you) a little bread, and sustain your hearts … ” Rashi points out that the words, “your hearts” are written “libachem,” with only one bais which implies only one heart and not “levavachem” with two “baisem” which implies two hearts. Rashi explains the reason for this is because angels have only one yetzer, the yetzer tov, and not two—a yetzer hora and a yetzer tov—like mortals have.

Considering that their guests had no yetzer hara, we see that Sarah’s modesty was an intrinsic part of her character—rather than a mere social or communal obligation. Sarah’s modest behavior was not simply a response to the needs of society or the people around her. When the angels visited, they had no yetzer hara—effectively removing any “practical” need for Sarah to stay secluded in the tent. Yet, she chose to maintain her modest stance.

This act served as a powerful demonstration to us, Sarah’s modesty was deeply ingrained in her very being. It wasn’t only for the sake of the community. Rather, it was a genuine expression of her innermost values and character.

If Sarah had practiced regular modesty—primarily aimed at contributing to the overall spiritual well-being of the community—she would still have been considered a righteous individual. However, the Torah specifically points out Sarah’s modesty in the presence of the malachim to highlight that it was intrinsic to her character—above and beyond the expected norms of righteousness. This suggests that understanding Sarah as merely “righteous”’ would not fully capture the exceptional nature of her modesty, which was deeply ingrained in her being.

This sets Sarah apart as exceptionally modest—even among righteous individuals—and it’s this kind of intrinsic modesty that we have to try to emulate!

HaRav Shimshon Nachmani—author of Zera Shimshon lived in Italy—about 300 years ago, in the time of the Or HaChaim HaKodesh. The Chida writes that he was a great mekubal and wrote many sefarim—including sefarim about “practical Kabbalah”—and asked that all of his sefarim be buried after he passes away, except for Zera Shimshon and Niflaos Shimshon on Avos. HaRav Shimshon Nachmani had one child who died in his lifetime (hence the name “Zera Shimshon”) and, in the preface, he promises for people who learn his sefarim after he dies, “ … And your eyes will see children and grandchildren like the offshoots of an olive tree around your tables, wise and understanding with houses filled with all manner of good things … and wealth and honor … ”

If you would like to automatically receive a dvar Torah of the Zera Shimshon every week send an email to [email protected].