Part III (continued from last week): Nazis Ascend to Power: 1941

Two years after the Russian invasion, the Germans attacked Russia. With Kletzk being only 7 miles from the Russian border, the Nazis were expected to imminently invade our hometown.

I’ll never forget how my family survived. It was on June 23, 1941, the day after Hitler declared war on Russia, and Herzl came into the house extremely agitated. His blue-grey eyes looked dark, his forehead had deep wrinkles; the 16-year-old boy looked like a man. “Mama,” he said, “let me have my heavy hiking shoes, a loaf of bread and some money. I am leaving with my friends over the border. We will ride on bicycles to Russia.”

Mother started crying. “You are my only son—I am not going to let you go.”

“The Germans send young boys to labor camps,” my brother responded. “My friends and I are crossing the border on bicycles. It is only 7 miles to the border. Please do not worry; I will go to your brothers in Moscow until the war is over.”

Mother decided that where her only son goes, the whole family goes. Father, on the urging of our 16-year-old brother, packed up the family to leave home and try to cross the Soviet border. We would return home when the war was over. We hastily packed some valuable items, clothing and bedding. My father loaned a horse from the government agency where he had been employed during the past two years of occupation. I almost forgot my diary, and ran back for it. My older sister, who was the best-dressed girl in town, made sure to take her high-heeled shoes, and my younger sister made sure to pack her favorite doll, which she always took with her. Herzl packed his atlas in case we would not be able to board a train and would have to proceed on our own.

At first, Bobbe Beylke refused to come with us. She explained that during World War I she had dealt with the Germans. Germans had acted like perfect gentlemen and were good to do business with. Besides, how could she leave the house and the garden she loved to tend? Finally we overrode her objections and she agreed to come with us. She gave the neighbors our house keys and asked them to air the house once a week and weed the garden. Bobbe Beylke paid them in advance for their service. She packed her photo album with the faded photographs of our ancestors, her Sabbath dress and shawl, her wedding gown that she had saved and her silver candelabra. She kissed the walls of the house and away we went.

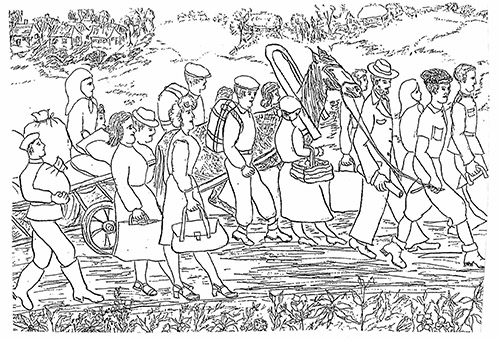

One day after the German invasion of Poland we left our hometown in a wagon, with Herzl directing the horse and Father directing him. The wagon was laden with our belongings on top of which the women in our family sat. Herzl was right to pack an atlas because the trains were reserved for the military and for retreating party officials. The rest of the population was jamming the highway leading to Minsk on foot, bicycles and wagons or whatever would carry them. Mother recognized some people from a nearby town and offered to put some luggage of theirs in our wagon. She also put a few small children onto the wagon. The poor horse was already struggling under our load, so Mother, my older sister and I got off to walk along with the others. Only Bobbe Beylke and our youngest sister Sima remained in the wagon, trying to fit in among the bundles.

We must have traveled about a mile when all of a sudden Bobbe Beylke announced, “Stop the horse! I am going back. Who is going to take care of the deaf-mute sisters when I am gone? Nobody will touch an old lady like me.” Bobbe Beylke jumped down from the wagon like a young girl as Herzl was coming to a complete stop. Father pleaded with her to remain with us but to no avail. She said goodbye to us and quickly walked back home. She looked straight ahead and never turned back once. We stayed still for a while, watching her in the distance as her figure got smaller and smaller. Her belongings were left with us. It was just as well because it was her candelabra that we would eventually exchange for food that helped us survive the first winter away from home.

That was the last we saw of her. Bobbe Beylke is buried in a mass grave outside her beloved hometown. We were later told by some survivors that the deaf-mute sisters were killed on the same day by the Nazis. Some peasants still remember Bobbe Beylke, her little store in the marketplace, her threads, buttons, needles, galoshes and boots and the little book with the “balance due.”

We were traveling the Brest-Minsk highway, and as we got further on it became more crowded with wagons, bicycles, people on foot carrying their possessions, and some mothers pushing baby carriages. We kept moving forward, caught in the inertia of moving bodies pressing onward. The horse stopped and couldn’t pull the wagon further. We all left the wagon, besides for Mother, Herzl and the little children. The horse pulled the wagon again. We walked behind it.

The countryside around us was peaceful—a few farm houses with straw roofs here and there surrounded by yellowing fields, and along the road grew wild flowers among the tall weeds. It was starting to get dark and our feet were hurting terribly. Our summer sandals were not fit for walking along highways. We tried walking barefoot but the soles on our feet burned. Father decided we should rest in the nearby woods; anyhow the horse needed a rest too.

The first night, I sat under a tree with my eyes closed, unable to sleep. The rest of the family, except for Herzl, seemed to be sleeping. Herzl was looking at his map with a flashlight. I walked over to him: “Are we heading in the right direction?” I asked.

Without looking up from his map, he quietly replied. “It all depends how fast the Germans are proceeding.” He looked up at me with compassion and finished, “Go to sleep, I’ll be watching out.”

Early the next morning we were back on the highway. Father left us for a while to go to the nearby villages for water and then caught up with us again. Between the excitement and the lack of sleep, I walked in a daze, struggling to follow the others.

(To be continued next week)

By Norbert Strauss/

Dr. Ida (Melcer) Zeitchik/Dorothy Strauss

Norbert and Dorothy Strauss are Teaneck residents. Norbert was general traffic manager and group VP at Philipp Brothers Inc., retiring in 1985. Dorothy worked as a senior systems analyst at CNA Insurance Company. Dr. Ida (Melcer) Zeitchik was Dorothy’s mother.