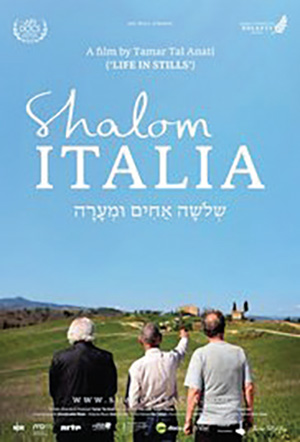

Reviewing: “Shalom Italia,” directed and produced by Tamar Tal Anati. Premiered on POV Monday, July 24, 2017 at 10:00 p.m. on PBS. View online at pov.org.

Elie Wiesel’s “Night” has shocked generations for its direct and stark portrayal of the Holocaust; in its clarity, the book forces readers to confront that reality in all of its detail. “Shalom Italia,” a new documentary from award-winner Tamar Tal Anati, may be “Night”’s perfect opposite, almost obsessed with the epistemological, rather than emotional, aspect of history. Every scene is saturated with the question: What do we really know about the Holocaust?

While that question seems shocking—and possibly offending—to many, it is particularly poignant in our “post-truth” age. And as the members of the Holocaust generation pass away, it is becoming ever more important to “set the story straight” and ensure that their travails are not forgotten. Tamar Tal Anati tried to capture this struggle in the film: “When I went to film [the movie], I knew that each one of them had a different way of telling his life story, a different way of memory…. [it] is very important for us to understand that the stories that we hear from the Holocaust are very very personal, and each of the people that went through it have a different perspective that is affected by their personality, character, age.”

In the coming years, our only living testament to those struggles will be the child survivors, who are themselves already older adults and whose memories are obfuscated by trauma. Such is true of “Shalom Italia”’s protagonists, the three Anati brothers, who were all under the age of 6 when they were forced to abscond to a cave in the Italian hillsides, in fear for their lives. The brothers, now in their late 70s, return to Italy in search of the cave that sheltered their family and, metaphorically, in search of their own memories.

The film, while ostensibly about this quest, is in fact centered more around the banter of the brothers, who appear unfettered by their Holocaust memories. “Those were wonderful times,” Andrea Anati recalls at one point, the irony thick. “We lived in the woods, played… I had fun during the Holocaust.” The brothers travel across Italy, visiting old homes and hiding places—always bickering, whether about details from their childhood or their favorite music.

It is, however, punctuated at times with moments of intense lucidity. During one of their meals, Andrea recalls meeting a woman who told him that she hid his father and brother in her basement as they sold jewelry to make enough money for the family to eat; the brothers unanimously agree that this must be simply a legend about them, as they distinctly remember that their father made his money from the family business. But their conversation comes to a startling head as Emmanuel Anati exclaims: “All the history that’s written in the textbooks is full of lies. No, no, no… We don’t really know what happened.” “Don’t say it didn’t happen,” Bubi responds—a desperate plea for truth. But he is too late, the sentiment has already been expressed, and it cannot be taken back.

These conversations, more befitting of Plato’s dialogues than a historical documentary, continue as the brothers drive through the countryside, recalling buried memories. When they meet up with a family that sheltered them in the early years of the war, it occurs to Emmanuel that “the only positive thing[s] that remains from this terribly gray, awful time” are themselves. Suddenly, the burden of the truth is much weightier, as they realize that they—who cannot even agree on how their father procured their food—must act as witnesses to their childhood years.

Underlying these collected travel experiences is the film’s main plot line: the search for the cave. The brothers’ quest for emotional tranquility is tensely drawn out for the entire hour; as the brothers argue about the cave’s location, one cannot be blamed for doubting the very existence of the cave, just as Emmanuel doubted his other memories. Time and time again the brothers fail to find the cave—one guide even claims that there are no man-made caves on this mountain. But finally, Andrea finds the outlines of it nearby, the roof having collapsed but the walls noticeably intact, and they can come to peace with their story.

“Shalom Italia” ends on this high note, as Andrea brings his family back to the site and plants a sign in the ground, physically marking its significance. Now their experience is set in stone for all to see, evidence that the truth does exist—right before our eyes.

Later, the brothers arrive home to find their family seated around a long table celebrating Passover. The symbolic meaning is clear: Just as Passover is celebrated thousands of years after the event, so too the Holocaust will be remembered long after its witnesses have passed away. The director notes that, in contrast to the earlier scenes where each of the brothers has his own distinct memories, here they “sit down and tell their family about what they found and what happened there—they retell the story as three brothers [together], which never happened before.”

“Shalom Italia” is a must-watch, both for its historical content and contemporary relevance. It premiered on PBS on July 24, and will be available online at pov.org through August 6.

By Dov Greenwood

Dov Greenwood is a recent Frisch graduate and a summer intern at The Jewish Link.