וַיִּתְרֹצֲצוּ הַבָּנִים בְּקִרְבָּהּ וַתֹּאמֶר אִם כֵּן לָמָּה זֶּה אָנֹכִי וַתֵּלֶךְ לִדְרשׁ אֶת יְדֹוָד:וַיֹּאמֶר יְדֹוָד לָהּ שְׁנֵי גֹייִם {גוֹיִם} בְּבִטְנֵךְ וּשְׁנֵי לְאֻמִּים מִמֵּעַיִךְ יִפָּרֵדוּ וּלְאֹם מִלְאֹם יֶאֱמָץ וְרַב יַעֲבֹד צָעִיר

(כה:כב-כג)

“And the children struggled within her (Rivka), and she said, ‘If it be so, why am I like this?’ And she went to inquire of Hashem. Hashem said to her, two nations are in your womb, and two nations will separate from within you. One country will be mightier than the other, but the greater one will serve the smaller one,” (Bereishis 25:22).

Rashi clarifies that when Rivka expresses, “if it be so,” she is reflecting on the intensity of her pregnancy pains and questioned, “Why am I like this?”—essentially asking why she continues to wish for and actively seek the condition of being pregnant.

Zera Shimshon raises two issues: Firstly, what is the meaning behind Rivka’s inquiry about her desire and ongoing prayers for pregnancy, given that she was already expecting? Secondly, why did Rivka seek guidance from Shem, who was a talmid chacham and a Navi—rather than consulting a physician—as her concerns were related to her physical well-being?

Zera Shimshon provides insight based on two teachings of Chazal.

First, in parshas Bereishis, the consequence Chava faced for eating from the Eitz Hadaas was, “I will greatly increase (harbeh arbeh) your suffering and your childbearing; in pain, you will bear children.” Chazal in Eruvin 100b interprets this to signify that whereas Chava initially bore children without pain, her sin caused her and all her female descendants to endure childbirth pain henceforth. But it is more than this. Zera Shimshon notes that the doubled expression, “harbeh arbeh” indicates a dual punishment; not only would there be labor pains, but sometimes, the punishment would extend to bearing a child who is inherently a rasha—as discussed in Yoma 82a.

Nevertheless, the Gemara in Sotah 12b explains that this decree does not universally apply. Righteous women do not fall under “the verdict of Chava,” implying they would not endure labor pains, and, consequently, Zera Shimshon argues, they would also be spared from the possibility of bearing a rasha.

In Mesechta Brachos 61b, Chazal offers an interesting insight into the human condition; an individual has the capacity to assess their own moral and spiritual standing. This self-awareness enables one to determine whether they are tzaddikim (the righteous) or the opposite.

Zera Shimshon combines the concepts that people can discern their own level of righteousness and that righteous women don’t necessarily need to suffer the “verdict of Chava” to address his questions.

Zera Shimshon explains that Rivka—who correctly self-identified as a tzadekes—was distressed by her severe pregnancy pains. This brought her two concerns: firstly, Rivka was puzzled about experiencing such pain if she was, indeed, righteous and supposedly exempt. Secondly, if she had misjudged her own righteousness and was not as virtuous as she believed, then this situation cast doubt on Chazal’s assertion that one can be sure of their own spiritual status, which she knew to be true. Catch-22!

Rivka’s predicament wasn’t just an abstract or philosophical issue; it had tangible, real-world consequences. It is written in the midrash that both Dovid HaMelech and Avraham Avinu approached Hashem with a request—if their potential offspring were not going to live righteous lives, they would rather not have children at all.

In contrast to Avraham and Dovid HaMelech, Rivka had assumed—based on her understanding that she was a tzadekes—that her righteousness would naturally shield her from the curse of Chava, which included the pains of childbirth and the risk of giving birth to a child who might choose a wicked path. With this belief, she had approached her prayers with an unreserved heart, asking for children without any stipulations—confident in the promise and protection her righteousness afforded her.

However, the onset of unexpected labor pains shattered this confidence. It forced her to reconsider her approach to prayer and the possibility that she might need to adopt the cautious stance of her forebears—to pray conditionally, specifying her desire for only tzaddikim as children and to entertain the thought that childlessness might be preferable to the risk of raising reshaim. This irreconcilable clash in her mind between her anticipated protection as a tzadekes, the stark pain she faced and how she should daven was what drove her to seek guidance on how to proceed.

Rivka was troubled by her uncertainty—rather than just the strong physical pain she felt—she naturally sought advice from Shem, a talmid chacham, instead of a doctor. How could a doctor help her decide whether to keep praying as before or to pray on the condition that her children be tzaddikim and not reshaim!

It is written in Chumash that Shem answered that she is carrying twins and this is the reason for her pains. How does this resolve Rivka’s confusion?

Zera Shimshon gives a fascinating explanation of Shem’s answer.

Shem assured Rivka that she could keep praying in her usual way, without needing to condition her prayers on having only righteous children. He explained that her discomfort was not a result of the “verdict of Chava,” but because she was carrying twins with contrasting destinies: Yaakov, the tzaddik, and Eisav, the rasha. Their struggle within her womb was central to Yaakov’s efforts to extract the hidden kedusha from Eisav, which was deeply embedded in him—a significant process that would impact future generations. This extraction would lead to righteous figures among Eisav’s descendants, such as Antoninus, Kitiya bar Shalom, and the Tannaim Shmaya, Avtalyon and Rebbi Meir. Shem emphasized that Rivka’s role in birthing Eisav was vital, as only through her and Yaakov’s virtue could the kedusha in Eisav be unlocked and redeemed. This situation was distinct from that of Dovid and Avraham, who would rather remain childless than father wholly wicked offspring. In Rivka’s case, bearing Eisav was essential for the greater good that his lineage would, eventually, bring forth.

Through this dvar Torah of the Zera Shimshon, we gain an invaluable perspective on how to interpret and navigate difficult and distressing situations in life. Zera Shimshon insights teach us that these challenges are not necessarily reflections of our personal failings and grounds for self-condemnation. Instead—much like the trials Rivka encountered—these situations may actually be opportunities assigned specifically for us, given to us because we, alone, possess the necessary abilities to succeed in them. They are divinely orchestrated moments where we are entrusted with a critical mission—to unlock and liberate the kedusha that is deeply woven into the fabric of these experiences. This perspective encourages us to look beyond the surface level of our struggles, recognizing the potential for spiritual growth and uncover hidden blessings. In this light, every challenging moment becomes a chance for us to act—to use our unique strengths and insights, just as Rivka did, to reveal and foster the sacredness that lies dormant within these trials.

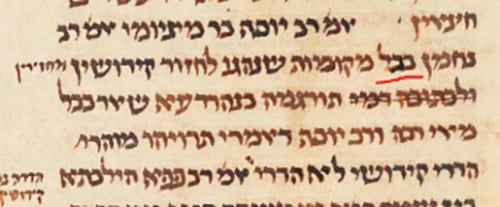

HaRav Shimshon Nachmani—author of Zera Shimshon—lived in Italy about 300 years ago, in the time of the Or HaChaim HaKodesh. He had one child who died in his lifetime and in the preface, he promises that those who learn his sefarim, “will see children and grandchildren like the offshoots of an olive tree around your tables.”