In Bava Batra 152a, Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak sat before Rava, and Rava was sitting before his teacher Rav Nachman (bar Yaakov), whereupon Rava asked Rav Nachman a question. (That question pertained to the true intent of something Shmuel, who was Rav Nachman’s direct or indirect teacher said, given another statement by Rav Yehuda, who was Shmuel’s direct student.) Rav Nachman waved his hand in response, and Rava was silent.1 When Rav Nachman arose to leave, Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak approached Rava to ask the meaning of this ambiguous hand-wave. Rava explained its meaning – according to Rashbam, it was either a dismissive wave or a gesture indicating strengthening, since the answer was בִּמְיַפֶּה אֶת כֹּחוֹ.

The interpersonal dynamics are interesting – Rav Nachman and Rava’s unspoken language and Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak not dealing directly with Rav Nachman, using Rava as an intermediary.

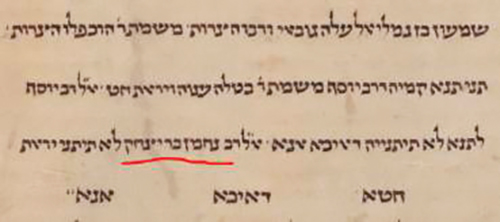

The same structural setup occurs in Eruvin 43b. Nechemia b. Rav Chanilai was engrossed in his learning and accidentally stepped beyond the Shabbat boundary. Third-generation Rav Chisda told Rav Nachman, “Your student is in distress.” Rav Nachman replied with an instruction to form a human partition. Now, יָתֵיב רַב נַחְמָן בַּר יִצְחָק אֲחוֹרֵיהּ דְּרָבָא, וְיָתֵיב רָבָא קַמֵּיהּ דְּרַב נַחְמָן. That is, the same players were in the same formation in the study hall. Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak asked Rava what Rav Chisda’s dilemma was, analyzed the possibilities, and then raised an objection.

Rav Aharon Hyman, in “Toledot Tannaim Ve’Amoraim,” maintains that such incidents, and the nature of their interactions, demonstrate that Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak was fourth-generation Rava’s colleague, rather than his student. Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak never quotes Rava but does quote Rav Chisda. Yes, he is also the colleague of fifth-generation students of Rava, such as Rav Pappa and Rav Huna son of Rav Yehoshua. He must have been a long-lived Amora of the fourth- and fifth-generations. When Rava was the rosh yeshiva in Mechoza, Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak was the reish kallah, chief lecturer, under Rava.

This all seems plausible, but I have some doubts and require further study (outside the scope of this article) about how to classify his interactions with third- and fourth-generation Amoraim. Does he speak to Rav Chisda directly? Are his interactions with Abaye and Rava, or support / attack thereof, typical of a student or teacher? When he sat in the row behind Rava, was this as a fellow student of Rav Nachman’s, or a grand-student whose direct teacher was Rava?

Identifying Rav Nachman

It is obvious from this incident that plain Rav Nachman is not Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak. Yet, this is a famous argument between Rashi and Tosafot, in which Tosafot claims that Rashi mistakenly believes that plain Rav Nachman is Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak.

In Gittin 31b, Rava and Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak were sitting together when Rav Nachman bar Yaakov passed by in a golden carriage with a green cloak spread over him. Rava went to him, but Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak did not go to him. He said, “Perhaps they are members of the Exilarch’s house. Rava needs them, but I do not need them.” Then he saw that the person in the carriage was actually Rav Nachman bar Yaakov, so he too went to greet him.

Commenting on “I don’t need them,” Rashi writes that Rav Nachman [bar Yitzchak] was the Nasi’s son-in-law, as we see in Chullin 124a. Looking at that sugya, plain Rav Nachman and Ulla argue, Ulla quotes Rabbi Yochanan, and Rav Nachman asks whether Rabbi Yochanan even makes his statement in a particular case. Ulla says “Yes,” to which Rav Nachman says, “By Gosh! Even if Rabbi Yochanan were to say this to me directly, I wouldn’t listen to him!” When Rav Oshaya (Rabba bar Nachmani’s brother) ascended to the Land of Israel, he related this Ulla / Rav Nachman conversation to Rabbi Ami, who was Rabbi Yochanan’s student. Either Rav Oshaya or Rabbi Ami said, “and just because he’s the son-in-law of the family of the Nasi, can he demean Rabbi Yochanan’s halachic statement?”

Tosafot in Gittin argue with Rashi on this point at length, proving that plain Rav Nachman is “bar Yaakov,” Rav Sheshet’s colleague, and that the only time that the Talmud bothers with Rav Nachman bar Yaakov’s patronymic – that is, “bar Yaakov,” – is when there are other Rav Nachmans with other patronymics and we need to disambiguate.

Did Rashi Write This?

Tosafot are clearly right. There are so many sugyot in which Rav Nachman is a different person than Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak, and in which Rav Nachman is Rava’s teacher. However, as Rav Aharon Hyman points out, our printed Gemaras don’t have Rashi identify “Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak” as related to the Nasi, just as plain Rav Nachman. In what seems like a forced answer, Rav Hyman argues that Rashi only meant to explain a different point. Namely, when Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak said דִּלְמָא מֵאִינָשֵׁי דְּבֵי רֵישׁ גָּלוּתָא נִינְהו, “that perhaps this is someone from the Exilarch’s household,” Rashi wanted to explain what the actual connection (to the Nasi) was.

Rav Hyman also points to Megillah 28b. A man who would study halacha, Sifra, Sifrei and Tosefta died. Rav Nachman declined eulogizing him, saying “Should I say, ‘Alas, a basket filled with books is lost?’” The Gemara then contrasts the harsh scholars of the Land of Israel – Reish Lakish, who was harsh but more considerate – with the saintly ones of Babylonia – Rav Nachman. Rashi there explains that “Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak” was the saintly one of Babylonia, pointing to Sotah 49a, where plain Rav Nachman says to an Amora reciting a Mishnah, “Don’t say that fear of sin ceased (with Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi’s death) for there is still me.” Rav Hyman explains that Rashi’s text probably was originally Rav Nachman bar Yaakov, which was shortened to RNbY, which was expanded to Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak. But Rashi doesn’t really make this identification.

I’m not convinced that this was Rashi’s intent. The dibur hamatchil in Gittin frames Rashi’s comment as why Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak isn’t wowed by the Exilarch family – he has his own prominence. Also, while printed Talmudic texts of Sotah have plain Rav Nachman, this statement appears after a (third-generation) Rav Yosef statement, and I’d expect Rav Nachman bar Yaakov (third-generation but deeming Rav Huna as a colleague) to precede. If Rav Yosef is in Pumbedita and reacts to the Reciter, perhaps the “Rav Nachman” should react to the same person, so he should also be a Pumbeditan Amora. Further, printed texts of Sota have plain Rav Nachman, but the two manuscripts, Munich 95 and Vatican 110-111, plainly spell out Rav Nachman bar Yitzchak.

Thus, a stronger solution for Rashi is that, in Sotah and Chullin, his texts did not have plain Rav Nachman, but spelled out “bar Yitzchak.” After all, Rashi never made an explicit assertion as to plain Rav Nachman’s identity. This was always only Tosafot’s extrapolation, based on their own texts.

Alternatively, might there be two plain Rav Nachmans? Names without patronymics occur in pockets, small social networks with no ambiguity. Plain Rabbi Eleazar can be “ben Shamua” or “ben Azarya” and plain Rabbi Eliezer can be “ben Hyrcanus” or “ben Pedat.” Later, when disparate texts join together, confusion emerges. Later Pumbedans may have referred to their reish kallah, who was local, as simply Rav Nachman. If so, we’d have to tease out which Rav Nachman was intended based on context.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Alternatively, I’d prefer it that וְאַחְוִי לֵיהּ בִּידֵיהּ, וְאִשְׁתִּיק means Rav Nachman merely waves his hand and was silent, not answering with words.