One might open a siddur, no matter the nusach, and assume that the prayers said on any given day were just as they were 2,000 years ago. But that simply is not the case. Some prayers do indeed trace back to biblical times, while others only go back a few hundred years. Indeed, siddurim across Jewish communities worldwide have been evolving for centuries. Now, with the groundbreaking “HaSiddur MiMkerotav” (available in both weekday and Shabbat versions), one can learn the full history of each prayer, complete with original sources and imagery of the earliest existing manuscripts.

The trailblazing HaSiddur MiMkerotav is the work of Moshe Tzvi Wieder. Originally from Ohio, Wieder spent two years at Yeshivat Netiv Aryeh and is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania. After making aliyah he had a successful career in computer science, serving on the executive level of several Israeli startups. Wieder always had a strong interest in the siddur and the history of tefillah, but had so many questions about why we say the prayers we do, how we say them (e.g., Standing or sitting? Bowing or not bowing? Heels raised or stationary?) and when they found their way into our siddurim.

“Three times a day you’re asked to have a conversation with Hakadosh Baruch Hu with a text that isn’t of your choosing,” Wieder recently told The Jewish Link. “It can be a strange experience. It becomes really important to understand where this came from and why it was chosen.”

Wieder had made a hobby of “siddur exploration” for many years, compiling notes on his academic research into the liturgy. Then a little over two years ago he decided he wanted to dedicate himself fully to creating this new siddur, leaving his chief information officer role behind and becoming what he calls a “liturgical archeologist.” The results are nothing short of remarkable.

“The siddur has never been a fixed book,” Weider said recently on the Seforimchatter podcast. “It’s evolved … and nusach isn’t quite as rigid as one might be trained to believe. The Rashba brings down that the Anshai Knesset Hagedolah gave us ‘key words’ they wanted us to use in davening, but no fixed text or prime nusach. Rather they gave us a framework.”

From Tanach to the Talmud, the Rambam’s Mishneh Torah to the Ari’s Sha’ar HaTefillah compiled by Rabbi Chaim Vital, to the shards and scraps of the Cairo Genizah, to responsa letters of great rabbis, Wieder left no stone unturned while compiling his new siddurim. Or rather, no scanned document not downloaded would be a more apt description. As Wieder pointed out, 20 years ago a scholarly undertaking such as this would not have been possible. Most universities and museums had yet to create digital copies of their ancient manuscripts, making text examination a difficult undertaking.

However, the vast majority of source manuscripts are now available online (although all the fragments of the Cairo Genizah have still not all been digitized), and many of them have been digitally restored and are featured in the siddur. In fact, Wieder’s source material was so vast, those who purchase the siddur will also get access to his online database featuring hundreds of pages of source material and at least 500 pictures of original manuscripts (some fragments, but many fully intact).

As a result of Wieder’s efforts, many fascinating discoveries have been unearthed. Think the tefillah of “Brich Shemay” (said before taking out Torah) is attributed to the Zohar? Well, Wieder went through 21 early manuscripts of the Zohar prior to its initial printing in 1560 and found the prayer in none of them. However, he did find two manuscripts from the 15th century attributing the tefillah to the Ramban (Nachmanides). Ever been in a shul when there’s confusion, debate, maybe even an argument about whether or not to say “shehem mishtachavim l’hevel varik, umitpallelim el el lo yoshia” in Aleinu? One can see that the earliest manuscript of Aleinu does include that sentence (so censor as you see fit). You might be aware that Shemoneh Esrei has changed over the centuries, but did you know there are at least 60 different versions documented through history? In short, you’ve heard of disruptive startups? Well, this is the disruptive siddur.

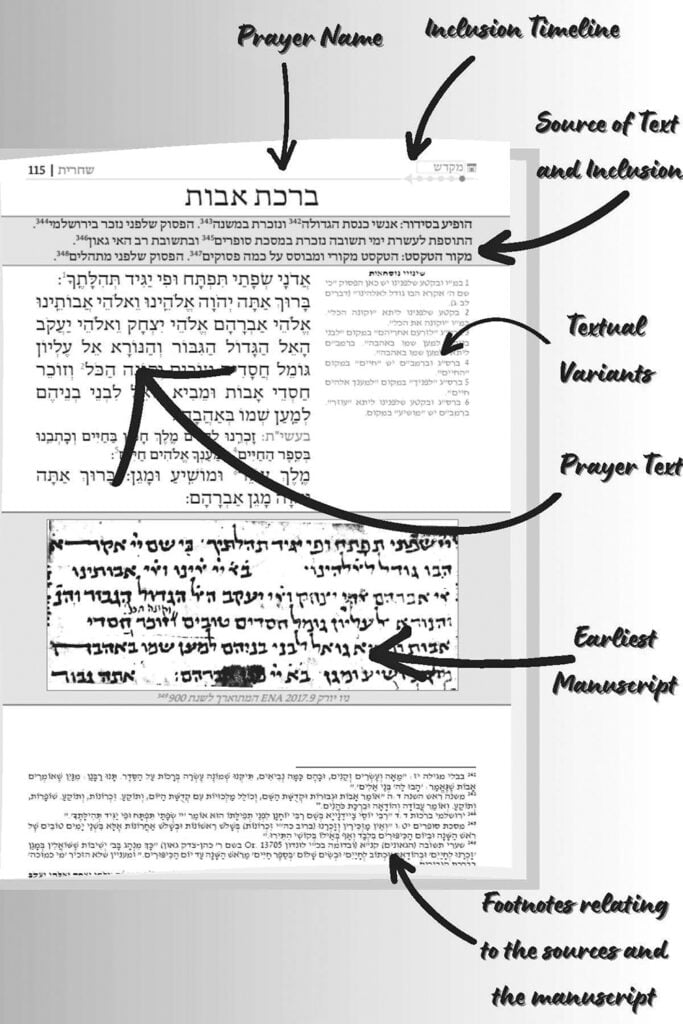

On each page of the siddur, Wieder lays out the tefillah as it’s commonly known, shows a picture of the earliest known manuscript, includes instructions when necessary, a timeline, and plenty of footnotes. While the siddur leans Ashkenaz in its formatting, Wieder makes sure to point out nusach and practice variations. For example, Shomer Yisrael is said during weekdays at standard Ashkenaz minyanim, but isn’t said at minyanim that daven Nusach HaGRA. Why is that the case? Wieder’s siddur gives the explanation.

Wieder has been surprised to find that the response to the siddurim has been greater on an international level than it has been in Israel. Though if you talk to any local rabbi or Jewish educator, you’re likely to see a mix of awe and excitement as they see the magnificent scope of Wieder’s siddur. “This is fantastic!” said Melissa Kapustin, teacher of Jewish history at Ma’ayanot. “This siddur adds a whole new dimension to the davening experience. Understanding how, when and where our tefillot developed can help make davening come alive and more relevant to students.”

Rabbi Marc Spivak of Congregation Ohr Torah in West Orange echoed similar enthusiasm. “Davening is about talking to Hashem. The tefillot help guide us in that conversation. It is exciting to see this new siddur, showing how that guide has changed throughout the years along with the messages they help foster.”

While the siddurim run about $60 each, including international shipping, they’re well worth the investment. The only “negative” about the publications are that following the English introduction in each sefer, the source notes, footnotes, timeline and instructions are entirely in Hebrew. Wieder is considering releasing an English version. Feel free to contact him at [email protected] and let him know if you’d be interested in an English edition. To purchase one of the siddurim, see sample pages, or find out more information, go to

siddur.wiederpress.com.