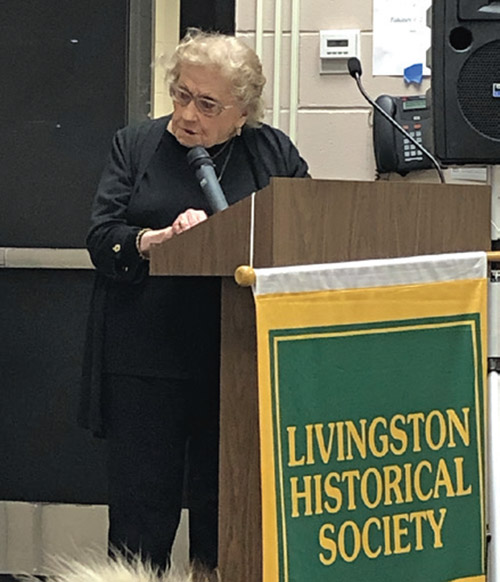

On January 27, the 75th anniversary of the Holocaust, survivor Melania Hoffman, 90, spoke at the Livingston Historical Society meeting in honor of International Holocaust Remembrance Day. In America 71 years, Hoffman spoke of her childhood in war-torn Poland for the first time.

Hoffman compellingly recounted the merciless killings that she witnessed. While many of the gory details remain trapped in her memory, she was able to share some of the important firsthand facts with the audience.

What made this presentation unique was that Hoffman walked to the podium wearing a noticeable cross necklace. Who was this survivor? Hoffman spoke for over an hour to 40 attentive listeners gathered to hear her testimony. The nonagenarian declared that what helped save her father, and allowed him to save their family, was talking with Jews. While her family was not Jewish, Hoffman revealed that her father learned their language from their Jewish neighbors, which contributed to their survival.

Several of Hoffman’s family members were in the audience, including her younger sister whom her heroic father saved multiple times during the war. The most incredulous instance was when the family was in a selection line. Their father reached behind the soldier, pulling his younger daughter back to him when he and his wife, along with Hoffman, were sent “left,” and the other child “right.”

Hoffman, at the tender age of 9 when the first bombs of World War II hit, described Warsaw as “beautiful.” That was until September 1, 1939, at 8 a.m., when the attacks started, and the first bomb fell two houses from theirs, killing her friend. All that was left were piles of stone with fire escaping. That was Hoffman’s first experience with the ravages to come.

Cautioned not to stay too close to the area, Hoffman’s family moved to her uncle’s house in downtown Warsaw, near a big marketplace. However, they couldn’t stay there long, as the planes hovered above, shooting people in the market.

From there they moved to the basement of her mother’s Jewish childhood friend. When they returned to their own house, they found it almost demolished. Only piles of ruins remained. That, Hoffman mournfully announced, was how their occupation started.

What the young children saw was awful, Hoffman commented, recalling that she saw a Jewish chasidic man shot. Hoffman said that when she was in school, she saw a 7-year-old girl running on the street when the Germans shot her.

While her father was only allowed to use Russian in school during World War I, now they were forced to learn German. Someone posing as a teacher gave them a date by which to bring their German books to school. He came to Hoffman asking, “Where is your German book?” The next thing she knew, he slapped her in the face. Hoffman admonished the German custom of hitting children in the face, even their own. Her teacher cautioned the students to be careful, insisting the man was not a Polish teacher, indicating he was sent by the Germans.

Hoffman spoke of witnessing five executions, of 10 people each, who were pulled off the street and arbitrarily killed. When they were finished, the Germans used a garden hose to wash off the streets and then the traffic went on. Hoffman insisted disgustedly that it was the German’s entertainment. Then they put up a red paper on the walls with the names of the victims.

“It was a horrible life,” Hoffman observed. Her father’s mother had 12 children, and the Germans forced her husband to work in a quarry and they never saw him again. Her grandmother’s Jewish neighbor Raisa had seven children and the two widows were very friendly. After the Germans blocked all supplies to Warsaw trying to starve them, her grandmother never saw Raisa and her children again. Hoffman’s widowed grandmother lost eight of her 12 children in a short period of time due to typhus and other illnesses. Only four boys survived and they remained in Warsaw.

On August 1, 1944, Hoffman, by then 13, recalled that the Warsaw Uprising destroyed 100% of Warsaw. The Russians were shooting heavy artillery on Warsaw, claiming that they were helping the Polish people; Hoffman said they could only be called savages.

Hoffman then spoke of the death of her grandmother. Facing machine guns in the courtyard, she refused to come out of her house. Her home was then torched, and at only 62 she was burned alive.

Describing more of the things that nightmares were made of during World War II, she mentioned hiding in the dark woods, the cattle cars with 60 people in one wagon, one loaf of so-called bread, no water, the camps, the lice, the showers, the naked bodies, the shaved heads and more. At one point, they went with no vegetables or meat for eight months. Their menu consisted of bread and water with green leaves of vegetables. Lunch was soup from greens of vegetables, and dinner consisted of one potato boiled in the skin with a pickle. She recalled the Germans yelling “be quiet,” Americans flying overhead in planes like bumblebees and the gate to the camp.

Pinpointing the September 11, 1944, raid as the biggest one, with the earth literally shaking for nearly an hour, she noted 34 other air raids before the war ended. By the time General Patton came to their area, it was a nightmare. Hoffman proclaimed, “God bless General Patton.”

After the war, her family lived in American-run displaced persons’ camps until they came to America in 1949. Albeit with very bad memories, Hoffman concluded, “We made it; it wasn’t easy.”

By Sharon Mark Cohen

�