Have you ever heard of dystonia musculorum deformans? If the answer is no, you are no different from everyone else I know, nor are you less knowledgeable than the many medical specialists in multiple fields who examined Cheri Belzberg, and whose diagnoses, for over two years of misery, ran a gamut of suppositions including those in the realm of psychiatry.

Except that this was no delusion. Something terrible had suddenly happened to Cheri, a happy and beautiful (she still is) young woman who until then had been a rebellious but exuberant teen—someone who went from being a hippie to beating anorexia to choosing to become a baalat tshuva, thanks to the wise direction of her non-observant parents. Studying at Stern College before disaster struck, she was enthralled by Jewish studies, becoming especially close to Rav Avi Weiss.

Cheri was about to become engaged to the young man who would prove to be the loyal, supportive—always there for her—love of her life, Harvey Tannenbaum, when odd and uncontrollable leg movements began to be part of every suddenly unbalanced step she took. One night, while making salad with her mother, she found she could not speak, and that whatever sounds she did manage were unintelligible.

When the rare form of dystonia that afflicted Cheri was finally diagnosed, that diagnosis came along with the awful fact that the cause of the disease is unknown and there is no cure, but that a host of different medications with agonizing side-effects would be tried out anyway. Cheri’s father, Samuel, (since passed away) a well-known philanthropist, established a research foundation to try to find a solution. As Cheri writes: “Ironically, the foundation helped many people, but not the one for whom it was created—me: The form of dystonia that I have does not fit into any of the recognized categories.”

She and Harvey had to bury their dreams of being a part of the young couples’ crowd, he with his friends and she with their wives. They are pariahs that make everyone uncomfortable, especially since when they got married, Cheri was still at the stage where the doctors thought her problems were a result of hysteria caused by her becoming religious.

But she has married the incomparable Harvey who doesn’t let her give up. “I still need a life partner despite your disability,” he says. And they become partners in the truest sense of the word and against all the odds (biz 120!).

Forty-five years have passed since that traumatic period. We would all empathize had the story of those decades included justified self-pity, withdrawal from society and a scathing or pitiful critique of how we treat those in the throes of chronic disease, those whose physical limitations make us uncomfortable.

Instead, all the frustrating attempts to be understood, endless pain, hospitalization, surgery, medications—and let us not forget humiliations—caused by the falls and other strains her body suffered, have been accompanied by Cheri’s strong marriage, three now-grown children—born against all odds—and a move to Efrat in Israel.

Before we can get choked up with admiration at how Cheri managed this much, we discover that this is only part of the story. After the onset of the dystonia and before making aliyah, Cheri attained a bachelor’s degree in psychology and a master’s degree in human development, learned jewelry making and worked at a mikvah as a balanit. This is in addition to the things she attempted but found herself unable or unwilling to complete, like a special education degree (she couldn’t stand in front of a class) or a shatnez (not for a romantic like Cheri) checker course.

The details in the book that fill in the bare bones of the outline sketched above make for a larger than life story that is a really good read—I read it at one long sitting on a Shabbat because I couldn’t put it down. Cheri’s sense of humor and wry self-deprecation, her healthy outlook on life and the revealing of her innate spirituality are what makes this book special. Cheri allows us to understand how she copes—whether she is designing her original (or should I say offbeat?) look in skirts and hats, her unusual jewelry and anything else she puts her creative mind to.

She admits that she can’t help waiting for the hoped-for day when she can lead a normal life, when a cure is found. But then she realizes that when you are faced with a test of this nature, that difficult way of living through every day is the normal.

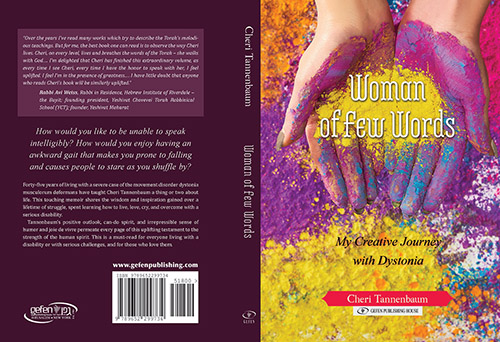

Why write the book, aptly named “Woman of Few Words—My Creative Journey With Dystonia” (Gefen Publishers)? One of the things Cheri hoped for while writing over a two-year period was to give strength and courage to others with difficult issues to face, but that aside, I believe that reading the book on its own merits is a profound experience. One cannot help but love and admire the phenomenal human being who wrote it, this indomitable woman who proves that one’s mind and mindset can be healthy even if one’s body is so very not.

Cheri has filled the book with wisely chosen quotes from writers who are not afraid to face the questions asked by those who feel God has forsaken them and who have dealt with their own difficult challenges, but there are also sentences and chapter introductions written by Cheri herself that go right into one’s heart and mind. Here are just a few:

“I always wear an upbeat look on my face, hoping that it will be infectious and people will see me and not my disability.”

“A disability is only limiting if you allow it to take over and define who you are as a person.”

“Giving to others transcends one’s self absorption.”

And wisest of all, for everyone to remember:

“Happiness is a choice.”

Despite her fighting spirit, Cheri’s life is a continuous uphill battle, but she keeps her eyes on the prize and reaches it just about every time. Her first child rejects her in favor of the nurse. She manages to win that battle, not without feelings of desperation. When her daughter is older and ashamed to bring friends over, Cheri holds dancing and other classes at her house and the girls come. When her children get married, she writes them tips for building a loving Jewish home that a marriage counselor would envy, and it almost makes up for her not being able to dance. Reading her brave words about the wedding, my eyes filled with tears. How that must have hurt!

What does Cheri do today? Art classes: beading, weaving, metal jewelry, collage, sewing, papier-mâché, all private lessons so they can be tailored to her often-changing ability to take part. She writes gratefully that luckily money was never lacking to help her achieve an optimum lifestyle. That is blessedly true, but I am sure her philanthropist parents never dreamed that she would be one of those who benefitted from their generosity to those less fortunate than they—and financially secure or not, she could have spent her life feeling sorry for herself anyway. Yes, there is a period of depression, but it doesn’t run away with Cheri’s life.

Reading the book, I had to remind myself that Cheri herself is in constant pain when she quotes the rabbi who said that courage is the ability to move forward despite pain. And somehow her feisty, funny and friendly personality shines through that pain and the cocoon of silence in which she is stranded until a medication for something else miraculously brings back her voice.

And while she is adamant that she is not an object to be pitied, not a miskena,Cheri admits that she is terrified of crowds because the floor she keeps falling to is her “second home.” And that it hurts that her children have to defend a mother who is “different”—but, they seem to be better people for it.

Cheri has written a frank and revealing book, asking: “What I Have Learned” and telling us “How I Carry On,” both of which serve as chapter headings. I found myself reading and rereading them to try to make them part of me as well. You will probably do the same.

By Rochel Sylvetsky/Arutz Sheva