The Pew Charitable Trust, on May 11, 2021, released the results of its Pew Research Center 2020 population survey of the American Jewish community. It last surveyed this group in 2013. Providing a generally nonpartisan, fact-driven survey about communal demographics and viewpoints, nonprofit organizations often use Pew reports to justify funding or direct new programs toward various populations.

The 2020 Jewish population estimate stands at approximately 7.5 million, including 5.8 million adults and approximately 1.8 million children. The 2013 estimate was 6.7 million, including 5.3 million adults and 1.3 million children. Orthodox Jews comprise about 9% of the Jewish population, a number that is consistent with its numbers from 2013. The Orthodox community includes about 500,000 children.

The Orthodox Union recently hosted a panel of communal professionals to delve deeper and provide analysis of the data. While the 248-page Pew study addresses many issues about Jewish life, Israel, antisemitism and observances (see here for the full report: https://www.pewforum.org/2021/05/11/jewish-americans-in-2020/), the Orthodox Union concerned itself in this panel with only a few issues specific to Orthodox communal vibrancy.

Consistency in size of the Orthodox community is attributed almost entirely to higher fertility rates and the fact that 77% of the Orthodox community is married compared to lower marriage rates in other denominations. “It’s not about transitioning into Orthodoxy. It’s about being born into Orthodoxy,” said Michelle Shain, PhD. Shain serves as assistant director of the Orthodox Union for Communal Research, and she was an adviser to the Pew study’s advisory board. In addition to speaking on the OU’s panel, Shain answered several followup questions via email.

“Orthodox Jews are marrying earlier than other Jews; have their first child about five years before, on average, other Jews; and have twice as many children, on average as other Jews,” she said. Child rearing and child bearing are generally how religious groups sustain themselves, Shain explained.

Shain added that as an adviser on the study, she was particularly interested in this line of questioning. “I personally pushed for collecting information on age at first birth, which wasn’t in the 2013 survey, and I was so happy it made it into the 2020 survey. This is why we now know that Orthodox Jews start having children at age 23.6, vs. 28.6 among non-Orthodox Jews.”

Interestingly, it is largely fertility rates that account for the stability of the Orthodox community’s population makeup. “We know that very few people who are raised as Reform, Conservative or unaffiliated become Orthodox as adults. Only 2% of those raised Conservative are now Orthodox, and only 1% of those raised Reform and unaffiliated. In other words, kiruv efforts have largely failed. The growth of the Orthodox community over the past 30 years is a result of early and high fertility among those born and raised in Orthodox families,” said Shain.

“Our most significant takeaway is our responsibility that is going to be hoisted on the Orthodox community in decades ahead,” said Orthodox Union Executive VP Moishe Bane. “With the enormous birth rate differential between the Orthodox community and the other parts of the Jewish community, as well as the age at the beginning of having children, you see a trend that means that the Orthodox community is going to play an increasingly significant role in American Jewry, just by virtue of numbers,” he said.

Of those raised Orthodox, 67% are still Orthodox; 10% are Conservative; 10% are Reform; 6% are no denomination; 1% identify with another denomination; and 6% no longer consider themselves Jewish. That means, according to a slide presented by Pew Researcher Alan Cooperman, that “for every person who has joined Orthodoxy, three people have left it.” Another way of saying this is that two thirds of American Jews who were raised as Orthodox still identify as Orthodox as adults.

“While we celebrate that high retention rate, I want to reconsider our investment in the one third we’re not retaining,” said Erica Brown, PhD, director of the Mayberg Center for Jewish Education and Leadership at George Washington University, noting that only 1% of Jews who were not raised as Orthodox have joined Orthodoxy.

“We tend, organizationally, as Jewish nonprofits, to focus on the Jews who ‘aren’t in the room.’

We have engagement campaigns, kiruv projects, outreach. The idea of engaging those who are not with us rather than deepening engagement with those who are, is highlighted in this report. I’d like to see a critical reassessment of this sort of strategy of focusing on outreach rather than higher retention rates, and doing more inreach,” Brown suggested.

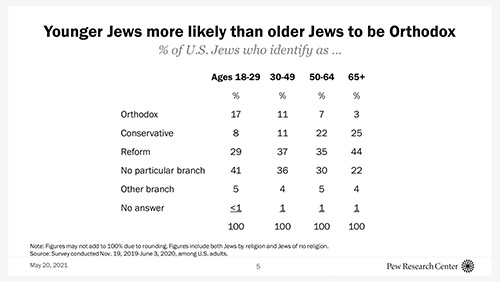

Also in the report, contrary to the study in 2013, younger Jews, those aged 18-29, are more likely than older Jews to identify as Orthodox—17% in this age bracket compared to 3% at age 65 or above. “Pay attention to the pattern,” said Cooperman. “That rising number is very indicative, as is the reverse pattern.” This means younger Jews are more likely than older Jews to be Orthodox. (See slide below.)

This younger identity unfolding as the average Orthodox Jew and the fact that people are largely happily living Orthodox lives are the most powerful things that struck Agudath Israel of America Executive VP Rabbi Chaim Dovid Zwiebel about the study. “75% of Orthodox Jews said their lives are filled with meaning and fulfillment. That’s a remarkable statement and something that is cause for celebration in a time when, I think, the idea of people speaking about meaning in their lives and leading fulfilling lives is a source of a lot of frustration in our society.”

Bane agreed that he believed the data showed that “the degree of commitment to the Jewish people around the world is dramatically greater when people are involved in the Jewish religion. 80% of Orthodox Jews feel a great deal of responsibility to fellow Jews around the world; the other Jews have much less [50% and lower],” he said.

The Orthodox community’s tendency to send their children to Jewish day schools, youth groups, summer camps and Israel trips could account for these positive associations. “Those types of immersive,

informal Jewish educational experiences are a key part of the socialization process of Orthodox young people, and we have lots of evidence that they have a positive impact on the participants’ Jewish trajectories,” said Shain.

With that in mind, she added, “I do think the Pew data should prompt us to take a careful look at kiruv efforts and ask what sorts of resources should be directed there, given how rare it is for Jews not raised Orthodox to become Orthodox.”

“The general social services that are being provided by the overall Jewish community today, the educational facilities, the mental health facilities, the needs [to address] poverty both here and elsewhere in the world, I think the lesson we’re learning is that the Orthodox community needs to start training its next generation to step up and play a role beyond the boundaries of Orthodoxy. To take responsibilities that are going to be theirs to bear, by virtue of their identity, and by virtue of their numbers,” said Bane.

Contrary to many populations that have high fertility rates, Orthodox Jewish women are exceptional in that they have high educational attainment. They are more than twice as likely as all Americans to have a college degree, and have an average of three children—well above the fertility expectations of the general public.

“The fact that the Orthodox population is expanding due to natural growth, not denominational switching, is in the report,” said Shain. “What’s not in the report is who within Orthodox families does the majority of the household labor and caregiving, and who carries the cognitive load. I suspect it’s the mom. A Jewish family’s most intimate decisions have an incredible impact on the Jewish people writ large.

“This is an unusual pattern,” Shain continued. “In the United States in general, more education is associated with lower fertility. In many ways, Orthodox women are caught with two sets of high expectations: as mother and as professional. And yes, I believe that since the reproduction in the Orthodox community is literally dependent on the labor of women, the Orthodox community needs to support those women.”

Shain suggested that one way to support Orthodox women is to provide professional opportunities that are flexible, where it can be possible to work part-time without a wage penalty. “Let’s make sure Jewish organizations and institutions take steps to enable part-time, flexible work for their employees.”

By Elizabeth Kratz