Before I get to Abraham Firkovich’s remarkable letter to the third Lubavitcher Rebbe, known by his magnum opus “the Tzemach Tzedek,” I’d like to address something. People sometimes ask me (yes, I mean you, Mom) about the nature of my interest in the Karaites and Karaism, so I’d like to take this opportunity to relay my thoughts on the subject.

As a young boy studying in yeshiva I was provided with a decent well-rounded education, but still I always felt that there was something missing. Tanach wasn’t studied so I made it my mission to go through it on my own. The same goes for Jewish history: I devoured every book on the subject. Since I was always fascinated by Jewish history, I had come across the Zadokim and the Karaites (although sharing quite a few similarities, the Zadokim were active during the Second Temple whereas the Karaites came on the scene in the Middle Ages. The terms were often interchangeable, with rabbis [e.g., Raabad, Ibn Ezra et al] often referring to Karaites as Zadokim) at a young age and was fascinated by this group of schismatics who apparently were still around. What did they believe? How did they come about, and why? As I delved more into it I realized that there was a lacunae in my education; nobody had ever bothered to tell me that quite a few things that we regard today as normative halacha came about in reaction to the Karaite heresy, or as Chazal put it להוציא מלבן של צדוקים. Two examples will suffice for now: 1) The emphasis on eating cholent/hamin on Shabbat afternoon is a fairly late innovation and it was clearly designed to offset the Karaite prohibition of letting a fire burn into the Sabbath (a stance that most Karaites eventually abandoned, by the way). 2) The blessings before lighting the Sabbath candles is also a late innovation that is not mentioned in the Mishnah or the Talmud, but rather comes into being during the Geonic Period when Karaism formed the greatest challenge to normative Rabbinic Judaism. The blessing on the Sabbath candles (as well as the custom to recite “Bameh Madlikin” on Friday eve) deserves a separate treatment, but it was clearly a reaction to the Karaite antipathy toward having a fire burn into Shabbat.

What intrigued me even more is the amount of material that was uncovered in the Cairo Genizah that showed a robust interaction between Karaites and Rabbanites in the medieval period. It showed marriages between the two groups, business dealings, religious disputations—sometimes rancorous—but never did either of the sides impugn the basic Jewishness of the other. It showed me how prominent Anadlacuan rabbis like Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra regularly quoted Karaite Biblical exegetes like Yefet ben Ali and others, sometimes disparagingly and sometimes approvingly. In summation, we cannot understand how our halachic system developed if we don’t look at how at least some of it was shaped and informed by the threat that Karaism once posed.

I had long advocated a thorough comparative study of various interpretations of Jewish law in order to better understand how our Sages arrived at their conclusions. I was deeply pleased when I saw this stance clearly enunciated in one of the letters by the brilliant first Chief Ashkenazi Rabbi of Israel, the famed Torah genius Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, who wrote the following:

In general, the way of learning should be: compare on every matter the Babylonian Talmud versus the Jerusalem Talmud and search through all the relevant sources: the Targumum, traditions, Geonic responsa, etc., up until the writings of the Achronim [the last halachic decisors]. In addition, one must investigate the works composed by those “on the outside,” such as gentiles, Karaites and see where they went straight and where they deviated. In general, one should use reason and common sense when learning—and minimize speculations and assumptions.

אגרות הראי”ה ב, עמ’ קפב

Now back to Firkovich. I noted last time the latter’s hostility toward chasidim and chasidut (a stance shared by his erstwhile rival Ephraim Deinard, incidentally), but like everything else about him, his stance was hardly uniform and harmonious.

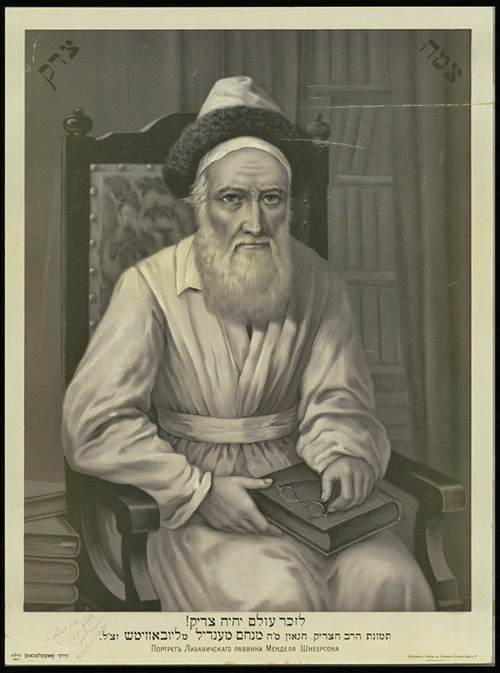

Dr. Golda Akhiezer of Ariel University recently published, for the first time, a letter from Firkovich’s personal archive written in 1856. This document is highly unusual and very interesting. It is addressed to none other than the third Rebbe of Chabad Lubavitch, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn. The issue at hand was a squabble within a Chabad family and the estrangement of a father toward his son. It is not immediately clear why Firkovich, of all people, was chosen to be the referee here (Akhiezer postulates that either he had a financial stake in this matter, or he wanted to improve his image after he had publicized some anti-Rabbinic screeds in the past). Of particular interest is the manner in which he addresses the Rebbe: with flowery titles and beautiful prose (which shows his deep familiarity with the sayings of Chazal). In this missive, Firkovich takes upon himself the unlikely mantle of national peacemaker and even extols the chasidic movement. In one part of the letter he writes about his concern for all of Israel, from near and far, for we all have one father. He promises the Rebbe that if he would take care of the matter, he (Firkovich) and the “sons of scripture” would come and prostrate themselves before him with great honor. Suffice it if I quote the flowery titles with which he crowns the Rebbe:

“A tree whose roots are many and its fruit-laden branches are planted on the tributaries of the water of Torah in keren ben shemen mishchat kodesh, he carried a branch and bore fruit of understanding…adept in the sea of Talmud…a child of holy seed and true wisdom, his vine has ripened, sweet to the wise for he is all holy, praiseworthy to the lord, my father, my father the chariot of Israel and its cavalry…the father of chasidim and the head of exalted ones…a prince in Israel like Menachem son of Uziel, beloved from on high and lovely in the eyes of the people, the stately lord, our master and teacher, adept in both the revealed and the hidden Torah, Rabbi Menachem Mendel, holy shall you say onto him, his name is great in Israel, blessed is his share in this world and the next, blessed is the nation that he is its captain…my lord! My lord! We have heard about you from afar, your good name has wafted to faraway places, we have heard and have exulted in the prospect of gazing at your face as if one gazes into the face of the lord, our souls have thirsted to speak with you about important matters that concern the welfare of the sons of your nation, our brothers the children of Israel whose welfare and success we seek, for we are all the children of one father and one God has begat us and bequeathed to us His holy Torah…”

You can read the entire letter as well as the context behind it at Dr. Akhiezer’s page at

This letter—as far as we know—went unanswered.

I’ll end with this: In his commentary to the Torah, the Tzemach Tzedek actually defends an explanation of the famed medieval Karaites exegete Yefet ben Ali that Ibn Ezra cites in a refutation! The fact that the Rebbe brings down a Karaite commentator’s explanation approvingly baffled some people, who came up with absurd explanations. The Israeli Chabad Rabbi Aharon Chitrik has a blurb about this here: https://tinyurl.com/5fnu4j87.

The author can be reached at [email protected].