A Mishnah (Chagigah 25a) mentions that amei ha’aretz, who aren’t particular about certain ritual concerns, are nevertheless trusted about the ritual purity of oil jugs during the oil-pressing season. This seemingly contrasts with a brayta that instructs the am ha’eretz who finishes [pressing] his olives to leave a sack of unpressed olives for a poor kohen, so that the kohen can press it himself in purity, rather than trusting the am ha’aretz. Rav Nachman bar Yaakov’s resolution is to distinguish between those who press early and those who press late. Rashi explains that those who press later, after the pressing seasons, aren’t trusted.

Rav Ada bar Ahava I then interacts with Rav Nachman in order to clarify the meaning of “late pressing”. אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב אַדָּא בַּר אַהֲבָה כְּגוֹן מַאי? כְּאוֹתָן שֶׁל בֵּית אָבִיךָ. “Such as what? Such as those of your father’s house.” This is ambiguous. Indeed, popular English translations differ. Artscroll has Rav Nachman responding, so it’s Ahava’s trees. Rav Steinsaltz has Rav Ada make a unified statement, so it’s Yaakov’s trees, explaining: “Rav Naḥman’s father had many olives, and he often pressed them after the regular pressing season.”

The ambiguity stems mainly from the lack of an אֲמַר לֵיהּ between the question and answer, as well as אמר being used for inquiries, statements and rhetorical questions. To resolve this, we can consider manuscript evidence, biography, scholastic interaction and linguistic usage.

Manuscript Evidence

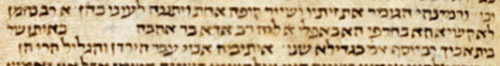

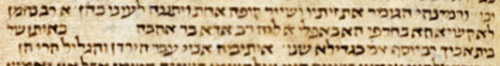

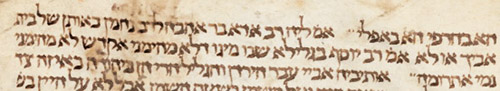

Several manuscripts have variants that may resolve the problem. I’ve only seen כְּגוֹן מַאי in printings. Two manuscripts1 have אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַב אַדָּא בַּר אַהֲבָה לְרַב נַחְמָן אֲפִילֵי הֵיכִי דָמֵי כְּאוֹתָן שֶׁל בֵּית אָבִיךָ. They simply replace כְּגוֹן מַאי with הֵיכִי דָמֵי, but retain the juxtaposed answer and ambiguity, “like those of your father.” These also inserted explicitly לְרַב נַחְמָן, which I suspect was a scribal attempt at clarification, that Rav Ada also answered. Several others2 omit the question and turn it into a statement, such as: אמ’ לֵהּ רַב אַדָּא לָרַב נַחְמָן כְּאוֹתָן שֶׁל בֵּית אָבִיךָ. Most interesting was Munich 6, which turned it into only a question: אמ’ לֵהּ רַב אַדָּא לָרַב נַחְמָן, כְּאוֹתָן שֶׁל בֵּית אָבִיךְ אוֹ לָא? Also interesting was the gap in British Library 400 between Rav Ada b. Ahava’s name and “like that of your father,” where the question would be. The manuscripts lean heavily toward Yaakov owning the olives, but the scribes seemingly are reacting to the irregularity.

Biography/Interactions

Could knowledge of the Amoraim’s personal lives help disambiguate? Rav Nachman was wealthy, and perhaps his father was as well. If the pressing was extended because of olive abundance, this indicates wealth. We know of Rav Ada’s great piety, but not his wealth.

Rav Ada (born 217) and Rav Nachman (born 230 CE) were contemporaries, and interacted as equals. However, Rav Ada was one of Rav’s great disciples, and was the conduit of Rav’s teachings to Rav Nachman. Perhaps here, Rav Ada instructs Rav Nachman about the legal parameters. Conversely, Rav Nachman himself makes the statement, so he should be the one qualifying it.

Linguistic Usage

We might consider how כְּגוֹן מַאי (“like what/whom”) and כְּגוֹן מַאן (“like whom”) are employed throughout Talmud, in relation to a subsequent כְּגוֹן. Four linguistic patterns emerge. (A) The Mishnah or brayta makes a statement, e.g., Shabbat 145b, an item cooked before Shabbat may be soaked in hot water on Shabbat. The Talmudic Narrator then asks “like what?” Then, an Amora clarifies, e.g., Rav Safra said, like Rabbi Abba’s hen. There are then two speakers involved in this כְּגוֹן מַאי כְּגוֹן chain: the Narrator asking and the Amora answering. However, we might alternatively regard it as rhetorical, as if Rav Safra’s quote extends backward to 3 כְּגוֹן מַאי. (B) Once (Sanhedrin 99b), the Narrator both asks and answers (with no named Amoraic reply). This chain involves a single speaker.

Next, (C) we have an Amora X ask כְּגוֹן מַאי and, without an intervening Y said, כְּגוֹן. Beside Chagiga, there’s Kiddushin 81a. While Rav and Rav Yehuda are walking, a woman walks before them. Rav suggests they change their path. Rav Yehuda points out that Rav himself said this is unnecessary for men of fit character, to which Rav says, “Who says I spoke of morally fit people like me and you? Rather like whom? Like Rabbi Chanina bar Pappi and his colleagues.” Alas, the speaker of כְּגוֹן מַאי is ambiguous. In a reversal of translations of our Chagiga sugya, Rav Steinsaltz has Rav Yehuda utter the כְּגוֹן מַאי, and Rav reply, while Artscroll makes it all Rav’s statement.

However, there is one unambiguous example. In Yevamot 36b, Rav Yehuda teaches his son Rav Yitzchak the verse in Kohelet, “And I find more bitter than death the woman.” Then, אֲמַר לֵיהּ כְּגוֹן מַאן? כְּגוֹן אִמָּךְ. His son asks, “like whom?” and the unattributed response is “like your mother.” The same pattern repeats with a positive verse, and the unattributed response is again “like your mother.” Clearly, Rav Yehuda is responding. Indeed, (D) the transferred version of this “bitter/sweet” sugya (Sanhedrin 22b) has an explicit speaker for both כְּגוֹן מַאן and כְּגוֹן אִמָּךְ, inserting inserts אָמַר לוֹ into both positive and negative exchanges.

To conclude, I lean toward Ahava owning the groves. All Talmudic examples can work with a speaker shift, and our sugya reads better with Rav Nachman clarifying his own statement.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 ואד אלחגארה (ר”מ בערך); מינכן 95

2 גטינגן 3; הספריה הבריטית 400; אוקספורד 366; וטיקן 134; וטיקן 171; Bologna, AS: Fr. ebr. 207; CUL: T-S F 3.98

3 For מַאי, see also Pesachim 49a, Avodah Zarah 28b. For מַאן, see Sanhedrin 99b; Bava Batra 8b, 90b; Horayot 2b; Bechorot 37a.