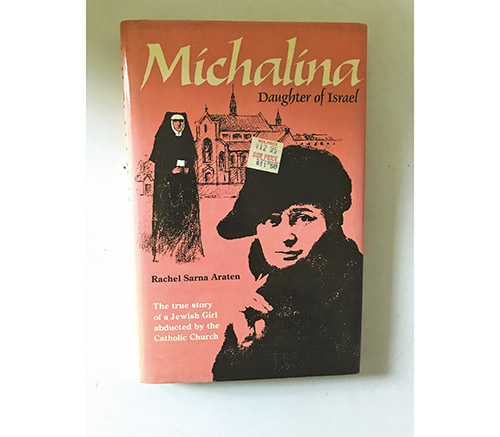

The scene must have looked exceedingly strange to the innocuous Israeli passerby: a chasidic man sporting a long beard and black and white attire weeping and hugging an older foreign woman and speaking to her in a mixture of Polish and German. The chasidic man is joined by his brothers who are likewise in shock at this unlikely reunion. The woman in question is not just anyone: It is their long-lost sister, and the tale that she tells contains twists and turns enough for a novel or a film. Her story has indeed been written up in book form by a relative. Michal or Michalina Araten was a young teenager in Cracow, the daughter of a prominent chasidic Jew named Israel Araten. Growing up in a large and prosperous chasidic family (as mentioned, her father was one of the most prominent adherents of the Polish Ger sect—then the largest chasidic group in the world), Michalina had everything she could have desired. But at some point something went wrong and she ended up in the Felician Sisters Convent in her native city, never to be seen again. According to the dramatic account given in the book “Michalina: Daughter of Israel” by her relative Rachel Sarna-Araten, Michalina was kidnapped by the family’s Polish Catholic nanny. Sarna-Araten’s book is a passionate and emotional account of a Jewish girl cruelly spirited away and separated from her loving parents by people intent on saving her damned soul. Michalina’s parents were frantic with grief and did everything they possibly could to get her released (including a personal appeal with the Kaiser Franz Ferdinand who promised to help) but to no avail: The convent refused to give her up, claiming that the child was there of her own accord and was determined to become a Catholic.

Sarna-Araten’s emotional account—written from the perspective of a family member—was published in Jerusalem in 1986 and not much research on the topic had been done since until recently, with the publication of Professor Rachel Manekin’s intriguing book “The Rebellion of the Daughters” (available at https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691194936/the-rebellion-of-the-daughters).

Manekin, relying on archival documents, paints a fuller picture of this strange occurrence that riled up the Jewish (and non-Jewish world) at the time. Manekin’s book explores three high-profile cases of young Jewish women who escaped their religious households. It begins with the case of 15-year-old Michalina Araten. According to the police and court files, young Michalina had decided to run away from home after she was punished for flirting with an Austrian army officer who was stationed in her town. The Felician Sisters Convent was known as a place of refuge for young Jewish women who wanted to escape from their home. In most cases these naive young women ended up there more because they had no other place to go rather than having been convinced of the truth of the Catholic faith. The year was 1899 and the education of young religious women in Poland was a complicated matter. It would be only decades later when a young Cracow native named Sarah Schenirer would come to the realization that Jewish women need a solid educational network if they were to be kept within the fold. That was not without much controversy (as Manekin describes in her book). Until then it was not uncommon for chasidic women to be tutored in secular subjects by private tutors. They would receive basic instructions on how to live a Jewish life from their mothers or hired learned women. This was obviously very unlike the kind of education allowed for the boys. To this day secular schooling is a highly sensitive and charged subject among chasidim. As one can imagine, this lopsided reality where the women were considerably more worldly and educated than the men created some tension for the women. Israel Aaraten was determined to match his daughter with a highly respectable family, and the bridegroom who was chosen indeed came from Galicia’s most respected scholarly circles. He was the son of Rabbi Chayim Elazar Waks, author of “Nefesh Chaya” and a renowned Talmudic genius. Michalina Araten was not pleased; she was consumed with anxiety, fearing that the hurried match was arranged for the family’s sake and her opinion was not sought. She may have planned an escape before this but this seems to have clinched the deal. When Israel found out the devastating news he undertook a campaign in the liberal and socialist press to free his daughter from her kidnappers, as he termed them. The case became a cause célèbre, with some likening it to the infamous Mortara Affair that occured in Italy decades before. Israel Araten, his family, his friends and his allies, among liberal gentiles, pushed the narrative that her captivity was an unjust wrong that needed to be righted. But Catholic Poland, even under the benighted goodness of the liberal Austrian Kaiser Franz Ferdinand, was deeply conservative and Catholic and nobody dared challenge them too much (ironically, most chasidic Jews in Galicia were politically aligned with conservative and Catholic political parties).

Israel Araten would get to see his daughter several years later after she was already married to a Catholic Pole and nursing a young child. Michalina would reminisce about that years later and recall how rivers of tears were shed at the time, but the wheels of time could not or would not be turned back, and Michalina, or Helga as she was now known, was to resume her life as a Polish Catholic housewife. Israel would never give up, and as the family moved on from Cracow and eventually made its way to pre-state Israel he enjoined his sons (his other daughters would be murdered at Auschwitz) to continue the search for her shortly before his passing in the 1950s. It was a chance encounter in the ‘60s that led the surviving Araten boys to the now widowed Michalina living in Warsaw with her married son and his children. She would eventually reconnect with her family and live out her remaining years in Haifa after receiving Israeli citizenship and maintaining that she was a Jew and not a Roman Catholic (whether she really meant it is still open to debate).

Manekin’s account of the case should be read along with Sarna-Araten’s narrative to get a complete picture. It is a microcosm of the story of our people.

The author is available to be a scholar-in-residence and can be reached at [email protected].