Earlier in March, I passed the balcony of the Hofburg Palace where, on March 15, 1938, Adolph Hitler announced the Austrian Anschluss to Nazi Germany. Approximately 200,000 Austrians stood on the Heldenplatz cheering that day. I watched the grainy black and white video of his speech, chilled with disbelief, as I stood in that same place. Moments later, I met with Wolfgang Sobotka, the president of the Austrian National Council, whose own grandfather was a Nazi.

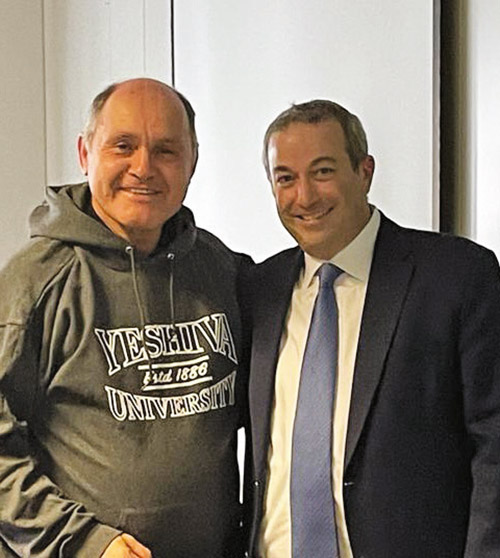

Sobotka was addressing our group of 28 Yeshiva University students that afternoon who were part of our emergency humanitarian mission to Vienna to work with Ukrainian refugees. With tears in his eyes, he told us his grandfather closed his last will and testament with the words “Always trust the leader.” Sobotka shook his head, lost in thought, “But his library contained the works of Schiller and Goethe,” as if beautiful literature alone can produce virtue. Sobotka himself has forged his own path as a fighter against antisemitism and a champion of the current Viennese Jewish community. Moreover, Sobotka and his country are responding to the current call of history by sheltering 1,000-2,000 new Ukrainian refugees a day.

Studying in New York, our students prayed on behalf of the Ukrainian refugees. They gave charity, tzedaka. But being heirs to a tradition that demands personal responsibility in the face of great human need, we understood that this was not enough. As the flagship Jewish university, we had to respond immediately and in person. And so Operation Torat Chesed was born.

In two days, we organized a group of student volunteers with over 100 students applying to be in the group of 28 students who were to join this trip led by our distinguished educators Rabbi Josh Blass and Dr. Erica Brown. We received a list of needs for the refugees, and students instantly began to raise money and collect items, including laptops to create an internet café to process papers and cell phones for refugees to be in touch with loved ones. Most of the refugees were women and children since men from the ages of 18-60 are either drafted to the Ukrainian army or awaiting notice. We met boys and girls who were not sure when they would see their fathers again. Within days of arriving, they were sent to new schools where they do not know the language but, at least, are given a daily structure with other children.

The students’ humanitarian efforts put them in contact with all of the Ukrainian refugees traveling through Vienna, with a significant amount of time focused on the Jewish community.

The Viennese Jewish community of 8,000 had already taken in 500 Jewish refugees and is expecting an additional 1,000 in the weeks ahead. Oskar Deutsch, the president of the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien, Vienna’s Jewish community, told our students that his council met to discuss how many refugees they could take in. But they refused to quantify the number or create a cap. “Can we take more? We have to. It’s our obligation. We have to take as many as we can.”

Students played games and did arts and craft projects on the floor with children, who represent 40% of the Jewish refugee population in Vienna. They also mopped floors, cleared out garbage, and prepared new hotel rooms to house incoming refugees. They went to the central offices of the community to work on a database and social media campaign. The charity drive they launched successfully raised over $100,000 to pay for a week’s worth of food for the refugees. They sat with refugees at meals and, sometimes with nothing more than the universal language of a smile, tried to bring comfort.

Humanitarian work can feel overwhelming. More than one of our students broke down during the trip, wondering how they could possibly make a difference in the lives of so many refugees, whose needs are so great and increase every day. Their volunteer work brought some insight to the answer. Narrowing millions of faceless refugees to a few hundred people with whom we had regular contact throughout the week enabled our students to forge a connection not with the “refugees” but with the person in front of them. We could not help everyone, but we could be present for the person in front of us, at this moment in their lives.

I opened with a view from the balcony, so to speak, and want to close with it as well. Nobel Prize laureate Elie Wiesel delivered a speech from that very spot—what the Viennese call Hitler’s Balcony—on June 17, 1992. “The balcony is nothing,” he said. “It is a symbol, nothing more. The purification, the change cannot come from the balcony. It must come from below.” We stood below that balcony and understood that while we pray that God brings peace to the region and shelter to the refugees, we cannot leave it all to God. In the Talmud, we have an expression, “Do not rely upon a miracle.” Our job is to create small miracles for others. By seeing the Divine in the face of every stranger and in the face of every refugee, we partner with God in the work of salvation.

May we see the blessings of peace flourish throughout the world.