Rav Sheshet was exceptional. A prominent third-generation Babylonian Amora, his expertise in Mishnah and braytot was so great that, when they met, Rav Chisda’s lips would tremble, worried that Rav Sheshet would shlug him up from a Tannaitic source (Eruvin 67a; Rashi)1. Rav Nachman asserted that both he and Rav Sheshet had learned Halacha, Sifra, Sifrei, Tosefta, and the entire “Gemara.” Rav Sheshet was also blind, either from birth or later2. Due to Rav Huna’s lengthy lectures, he became impotent (our sugya, Yevamot 62b). Each of these qualities—prominence, intense Torah knowledge, blindness and impotence—set him apart and change what we derive from his scholarly statements and actions, perhaps unfairly.

For instance, his intended path took him under an Ashera tree (Avodah Zara 48b). Being blind, he asked his assistant to hurry him through that area. Usually we deduce halacha from a practical action and application (מעשה רב). After analyzing whether such is required and in which situation, the Talmudic Narrator, centuries later, explains that really, there was no alternate path, and a typical person in such a situation could traverse it. Since Rav Sheshet was a prominent person (אדם חשוב), he was different3 (e.g., lest people see his actions and overapply them to incompatible situations).

When the tzibbur were leining the Torah in shul, Rav Sheshet would turn his face away and learn his Mishnah, saying אֲנַן בְּדִידַן וְאִינְהוּ בְּדִידְהוּ, “we are engaged in ours and they in theirs” (Brachot 8b). I’d argue he was asserting that the typical person engages in studying Torah in his/her own level, and the weekly Torah portion was appropriate, but Torah scholars who are capable should engage in their own level of study. Thus, “we in ours.” Congregation Beth Aaron has Daf Yomi an hour before Mincha in the Main Shul, but they should really just gather together during kriat haTorah. Rishonim grapple with this and minimize its practical application, especially given Sotah 39a that once the sefer Torah has been “opened” one mustn’t speak, even in matters of halacha. Perhaps this is only studying by oneself. This is only if 10 others are paying attention to leining. Tosafot follows Rif who says שָׁאנֵי רַב שֵׁשֶׁת שֶׁתּוֹרָתוֹ אֻמְנוּתוֹ הוּא, Rav Sheshet was different because Torah was his profession. Tosafot in Sotah advance the same, but also suggest that רַב שֵׁשֶׁת שָׁאנֵי מִשּׁוּם דַּהֲוָה מְאוֹר עֵינַיִם, Rav Sheshet was different since he was blind, and was exempt from studying written Torah. “We with ours” referred to blind people4.

A tanna recited a brayta before Rav Sheshet that seeing a snake in one’s dream indicates accessible livelihood; if it bit him, his livelihood would double; and if he killed the snake, he’d lose his livelihood (Brachot 57a). Rav Sheshet told the reciter, au contraire, if he killed it, all the more so his livelihood will double. The Talmudic Narrator doesn’t find the logic persuasive, and explains that Rav Sheshet had seen a snake in his dream and killed it, so was biased and/or sought to interpret it positively5.

Finally, in our sugya (Yevamot 62b), after a brayta indicates that grandchildren are deemed like children, Abaye (fourth-generation Amora, Pumbedita academy) and Rava (same) discuss whether one fulfills the precept of procreation if his direct children have died in his lifetime but their children yet live. A daughter’s daughter, a daughter’s son, and a son’s son all fill their parent’s place but, for Abaye, not a son’s daughter. Rava argues that the whole point is that (Yeshayahu 45:16) Hashem created the world not to be desolate, but to be inhabited, לשבת יצרה, so here too, he’d fulfill. The Talmudic Narrator, noting that Abaye and Rava only discuss one child from each branch of the family tree, deduces that neither would credit only a single branch surviving with two grandchildren6.

This supposition runs counter to Rav Sheshet’s apparent position. His rabbinic colleagues suggested he remarry and have children/sons, and he responded that his daughter’s sons were considered his sons. The Talmudic Narrator explains this as a polite push-off; Rav Sheshet didn’t actually maintain this position. Rather, he was impotent from Rav Huna’s lengthy lectures.

That is, Yevamot 64b relates that Rabbi Abba bar Zavda’s rabbinic colleagues suggested he remarry and have children. His rejoinder was that had he merited, he would have had children from his first wife. This contrasts with the Gemara’s, or the Mishnah’s, prior theological assumptions. The Talmudic Narrator explains this was a polite excuse—for he was impotent from Rav Huna’s lengthy lectures. This is followed by a list (in identical language) of Rav Huna’s students who became impotent in this way: Not only he, but Rav Gidel7, Rabbi Chelbo8 and Rav Sheshet. Rav Acha bar Yaakov was initially affected (with סוּסְכִּינְתָּא), but he successfully applied a cure9. Rav Acha bar Yaakov relates that he was among 60 sages who all became impotent from Rav Huna’s lectures, except for himself, for he fulfilled (Kohelet 7:12) “Wisdom preserves the life of he who has it.”

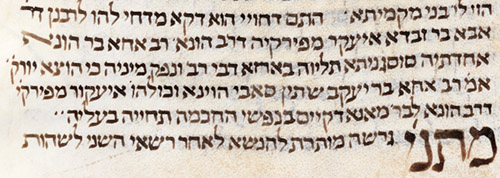

Curiously, not all manuscripts have our full text of Yevamot 64b. Munich 95 and Munich 141 both skip the list of Rav Gidel, Rabbi Chelbo and Rav Sheshet becoming impotent. They have a different Amora (Rav Acha/Adda bar Huna) than Rav Acha bar Yaakov recovering from סוּסְכִּינְתָּא, and then have Rav Acha bar Yaakov discussing the 60 Sages who became impotent.

The omission is easily explained as haplography. There’s repetition of אִיעֲקַר מִפִּרְקֵיהּ דְּרַב הוּנָא, so a scribe could have copied the first occurrence, for Rabbi Abba bar Zavda, looked back, and then copied from after the last occurrence. However, the alternative is to note that it’s the Talmudic Narrator who is proposing this for Rav Sheshet and Rabbi Abba bar Zavda. This could be based not on the anonymously sourced Talmudic list, but from the named Rav Acha bar Yaakov’s declaration regarding 60 Sages. After the local suggestion of Rabbi Abba bar Zavda’s impotence, a Talmudic Narrator or a scribe might identify and insert other students of Rav Huna, based on logical inference; see footnotes explaining each inference. If so, perhaps Rav Sheshet is simply iconoclastic in his actions and positions, and we shouldn’t dismiss these as resulting from his unique lived experiences, thereby stripping them of potency.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

1 Rav Chisda was no slouch either; Eruvin 67a notes that Rav Sheshet’s entire body would shake from Rav Chisda’s sharpness.

2 Rav Aharon Hyman proves this from Brachot 57a, where Rav Sheshet saw a snake in his dream and killed it. Someone blind from birth wouldn’t “see” anything while sleeping, since there is no waking experience of vision from which to draw. But I’ll argue against this proof. Also, he points to Bava Batra 9b. Rav Achdavoi bar Ami had responded to Rav Sheshet in a mocking tone, implying that Rav Sheshet didn’t know Biblical verses. Rav Sheshet took offense; Rav Achdavoi became mute and forgot his learning. “His” mother (with the antecedent being either Rav Sheshet or Rav Achdavoi, as per Rashi or Rabbenu Chananel) came before Rav Sheshet, asking him to pray for recovery, and after he ignored her, said “see these breasts from which you have suckled.” Again, sight is assumed. However, perhaps she simply meant to take heed.

3 See Dr. Tzvi Arie Steinfeld, “Adam Chashuv Shani,” in Dinei Yisrael 13-14, https://tinyurl.com/mmw999ae, where he discusses the phrase rarely used by named Amoraim and more frequently used, perhaps in a different manner, by the Talmudic Narrator.

4 Still, if anyone’s interested, let’s approach Rabbi Rothwachs and see if we can arrange it.

5 Note that this is the Talmudic Narrator, much later, who said Rav Sheshet saw this. Instead of showing he wasn’t always blind, perhaps his blindness is evidence against this dismissal.

6 While possible, another explanation is that Abaye and Rava were focused on the cross-gender issue, which is simplest to frame in a child assuming the parent’s place. Rava’s motivating principle of לשבת יצרה would seemingly apply equally to this new case.

7 Ramban points out that regardless of Rav Sheshet’s polite excuse, he disagrees with the Tanna Rabbi Yehoshua earlier in the page, who said that even if one married in his youth, he should marry in one’s old age; this, because of Shmuel’s assertion (61b) that even one who already had children must remarry, and that it is forbidden to remain without a wife. Ramban suggests that, alternatively, there’s no contradiction, if this impotence also removed the sexual drive. To bolster this, I’d note Rav Gidel on this list. He’d sit at the entrance to the mikveh and instruct the women how to immerse (Brachot 20a). His colleagues asked if he feared the evil inclination. Rav Gidel replied, “In my eyes, they are like white geese.”

8 Rav Chelbo fell ill and had no one to visit him (Nedarim 40a), perhaps indicating that he lacked a family.

9 Indeed, he had a daughter (Sotah 49a) and a son (Menachot 43b).