Barbara Gilford, a retired therapist living in Morristown, New Jersey, had an exciting childhood filled with international travel and top-level academic and cultural education. She achieved success in several careers: teacher, journalist and therapist, while marrying and raising two sons. But at her core she felt a lifelong insecurity about who she was, with an ever-present sorrow that she never knew her paternal grandmother, aunt, uncle and cousin whom she had only heard about and saw in photos; they had been murdered by the Nazis before she was born. Finally, she became an author to come to grips with her family’s past, and her thirst for answers about what had happened to those she loved but had only hugged in her imagination.

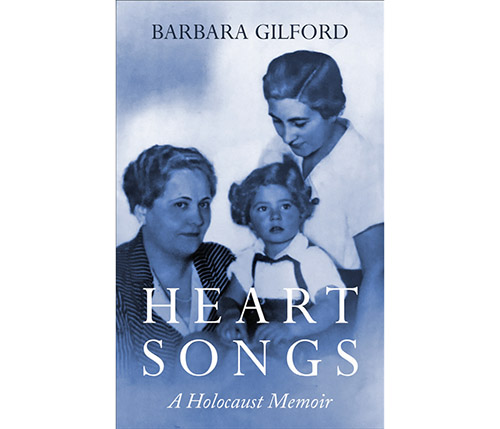

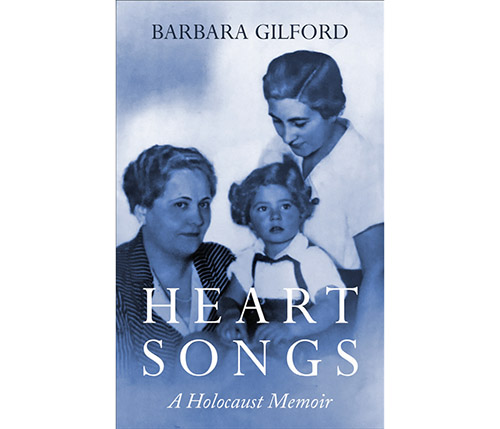

In “Heart Songs: a Holocaust Memoir,” Gilford fills in the outline of the Buchsbaum family story with meticulous research and trips with her two sons to the places where the family once lived.

Gilford knew the basic chronology from her father’s oft-told stories and a loose-leaf with 100 pages he typed about the family history. But then she discovered a real treasure. After both her parents had passed away, Gilford moved some of their possessions into her home. One day, 20 years later, Gilford began cleaning and discovered a folder with letters her grandmother had written to her father. Gilford had the letters translated, which filled in some of the narrative, and gave a voice to the woman she had only known through photos and her father’s memories.

In her introduction, Gilford writes: “The letters led me on an odyssey into Europe and my grandmother’s heart that I never could have imagined. They carried me into my own nether regions where I continue to grieve the loss of something I never really had.”

She initially wrote the book for her family’s eyes only. But a writing coach and friends in her workshop convinced her that the story had wider appeal. What makes the book engaging for readers beyond the family is how she fuses the past and present, using her therapist’s toolkit to raise and confront troubling questions, and a writer’s skill to make the reader care. Reading “Heart Songs” feels like sitting down with a close friend as she pours her heart out to you.

The family had lived a happy, prosperous life in Ostrava, Czechoslovakia, but like many Jews, were in denial about their fate until very late. Gilford’s father was able to make his way to England, and ultimately the United States. His journey could have gone wrong many times, and Gilford documents the twists and turns. Her grandmother Clara was not as fortunate. She was able to get to Italy, where she wrote the letters Gilford found.

As translated, Clara’s letters are rich with love and longing, like this excerpt from one from November 27, 1941, in which Clara wishes her son a happy birthday: “All my thoughts and blessings, my very beloved good child, will be with you on this day, they always find a way to you, they are the goal of my dreams for the future…I sometimes dream about you and the beautiful and happy times when you and Gretele were with me, and then I am sad when I wake up. But it will certainly be better again one day and how happy we will be then together. Then we will be able to value the great joy more than before when we took it for granted…”

The documents Gilford found with the letters were enough to let her trace her grandmother’s steps. She was able to visit the home in Italy where her grandmother had lived. She met the owner’s daughter, who had lived there as a child and remembered Clara. Gilford learned that her grandmother and two other women living in the home were betrayed to the Germans and sent to Auschwitz. Later research confirmed that Clara’s daughter Gretele; Gretele’s husband, Hugo; and daughter Susi died in Treblinka.

When Gilford writes about her own childhood, she recalls her feelings about never fitting in. Her father’s military career took the family to many places—Washington, DC; Heidelberg; New York; Baltimore; Berlin; and back to New York. The family went to services on Fridays and she attended Sunday school. She had a privileged, assimilated childhood in Heidelberg, with lessons in ballet, ice skating, piano and horseback riding. She writes about the sporadic anti-Semitic incidents that intruded on her otherwise happy life. “I knew my family was different because we were Jewish and my father spoke with an accent. In our years in Heidelberg I became aware of my Jewish identity. There were no other Jewish children in my grade during our time there. My classmates asked, “What are you? Protestant? Catholic?” My jaw tensed as I tried to form the ‘J’ sound. I flushed with shame that I was Jewish and then felt guilty about my feelings. Did being different mean I was inferior?”

Gilford now proudly embraces being Jewish. When she decided to get a master’s degree in social work, she went to Yeshiva University. “I was ecstatic,” she said in a phone interview. “It was my first time learning in a large group of Jews. Some were the children of survivors. That was the beginning of this very proud and satisfying Jewish identity.”

Gilford joined a synagogue seven years ago and is working to create a digital memorial registry there where first- and second-generation survivors can make entries about family members who perished in or survived the Holocaust. Last year, she filmed several members who had surived the Holocaust and put their stories on her synagogue’s website.

“Heart Songs” is Gilford’s memorial to her family. She writes, “The inexorable link between memory and love ensures that we of the second generation will always remember. For me, the mandate of obligation has become a loving choice informed by getting to know my family; reciting their names; and telling their vibrant, courageous stories.”