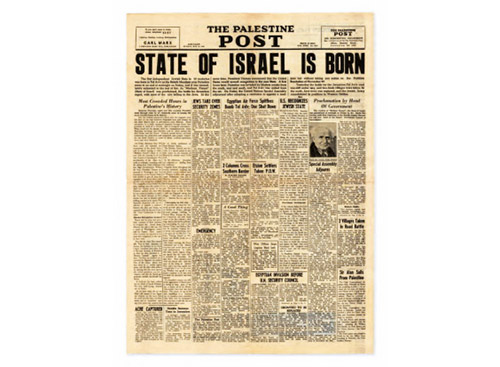

It was 11:15 p.m. on Saturday night, and the energy in the room was frenetic — a group of journalists stood eager to report on the events of the day and a fledgling nation waited with bated breath to read all the details.

But this was no ordinary Saturday night. It was Saturday night May 15, 1948. The new state of Israel — Medinat Yisrael — had just been proclaimed by David Ben-Gurion a little more than 24 hours earlier, the British had just evacuated their last officers, and Arab armies were attacking from all sides.

The sound of teletype machines, typewriters and printing presses filled the room, along with the crackle of gunfire in the distance. Editors scrambled to assemble the incoming communiqués, writers were working to articulate the details of the war, and emotions were running high. There was excitement in the air, but also great anxiety.

Would the hundreds of Haganah men and women fighters survive in the Kfar Etzion block near Hebron? Would Tel Aviv be destroyed by Egyptian Spitfire aircraft? Or by the two columns of Egyptian troops and artillery that just crossed the southern border? What was the status of the battle for Jerusalem and the Old City?

On the diplomatic front, many questions remained unanswered. Did the United States recognize Israel? Would they lift the arms embargo? Will Russia recognize the new state? What would be the outcome of the United Nations Special Assembly session?

The very existence of Israel was at stake. Tel Aviv was blacked out on Friday, Jerusalem was under a state of emergency — the first order issued by a Jewish commander in almost 2,000 years — but a newspaper needed to be published.

The newspaper was the Palestine Post. Founded in 1932 as part of a Zionist-Jewish initiative, the newspaper’s intended audience was English readers in Palestine and nearby regions — British Mandate officials, local Jews and Arabs, Jewish readers abroad, tourists, and Christian pilgrims. The publication supported the struggle for a Jewish homeland in Palestine and openly opposed British policy restricting Jewish immigration during the Mandate period, and was considered one of the most effective means of exerting influence on the British authorities.

And then, suddenly, as if a mysterious hand flicked a switch, darkness descended upon the room. There had already been a blackout ordered for the entire country that day due to the new war, but the electric company succeeded in providing the office with power at 10:15 p.m. Then, just an hour later, there was a new power failure and the paper had to wait to be published, if at all.

That was a most special day of course, and with a lot of determination, at 1 a.m. power was restored, the linotype machines clanked back to life, and the most historic newspaper in 1,900 years barely eked out a single two-sided broadsheet.

Seventy-four years later, in 2022, Arthur Ganz, an art director who has a love for print, stepped into a Jerusalem antique store and his eyes lit up when he saw an original newspaper for sale.

As a child he had already developed an interest and appreciation of letterpress printing. In 1967, as a young impressionable 9-year-old boy, he had watched the mesmerizing rhythm of his grandfather’s Heidelberg printing press in Toronto. He watched as his grandfather’s hands, blackened by ink, turned on the hulking machine, and as tiny suction cups lifted sheets of paper, snapped them into place for the steel plates to mightily crash their impression on them. He remembers being handed the printed card — it was a wedding invitation — and how he ran his fingers over the paper, feeling its texture. It was an immersive sensory experience of sight, sound and the smell of fresh ink, all combined into one.

Those memories resurfaced that day in the Jerusalem store as he gingerly ran his hands over the antique newspaper. And at that moment he knew he had to buy it.

Excited to frame and hang it, he learned of some troublesome news. Displaying it on a wall would expose it to UV light which could make it not only fade and turn yellow, but also turn brittle. Historic documents need to be protected in acid-free archival materials and stored in cool dry conditions.

As a graphic artist he knew he could digitally scan the original, but that just wouldn’t do it justice.

He had a grander, and some would say crazy, idea. “What if I were to reprint the newspaper using the exact same techniques as was done 75 years ago? Would that even be possible?” he asked himself.

And so, his journey began.

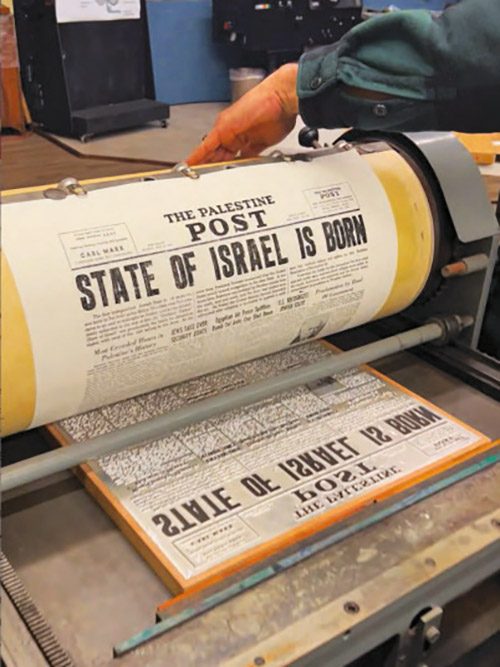

Using his many years of design and printing experience, along with some tenacity and persistence, he set out on a challenging mission. He located a company that still made letterpress plates. Entering the building, he was suddenly transported back in time. “It was like stepping into a time machine to 1977 when I had first started working at a printing company. Paper job tickets, a huge bellowed camera, dark room, light tables for stripping and opaquing film negatives, vacuum frames and acid baths for making plates. It was surreal.”

Together with a veteran cameraman he placed the original newspaper in the camera and then watched excitingly as the headline “STATE OF ISRAEL IS BORN” and the image of Ben-Gurion appeared on a huge sheet of film.

He then supervised and participated in the many stages of platemaking: magnesium being exposed to UV light, then bleached, acid-sprayed in a huge steel tank, washed, gouged, and mounted on a block of cherry wood.

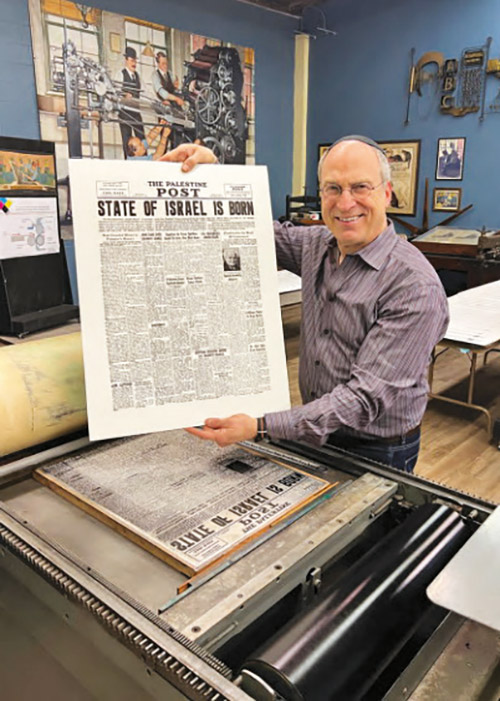

With plate in hand, and beautiful 100% cotton paper from Cranes (the company that manufactures the paper used in U.S. currency) procured, he located one of the few remaining places in America that had vintage presses large enough to print this heritage piece. But then his heart skipped a beat when he learned that it was an educational museum, and not a trade or commercial printer open to the public.

Not to be deterred, he took a chance and called the director of the museum. He described the project and the historic nature and conditions of the original publication, and his heart skipped a beat again when the director said “Let’s do it!” It would have to be done on a hand-operated vintage 1962 proof press and the process would be very slow, feeding one sheet at a time and rolling it over the plate with a significant amount of muscle, but at this point he was running on adrenaline. He rushed to the museum — a nostalgic and sentimental experience itself — where they mounted the plate, inked the press, and ran several test sheets to get the positioning and ink pressure just right.

He recalls the moment the first sheet came off the press: “Here I was, printing something historic, in the same way it was done in 1948! The reproduction came out breathtakingly beautiful — all the nuances of the typography of the original newspaper, including uneven columns, broken type, and tiny impressions between individual letters — were authentically reproduced. I thought it remarkably accurate and in many ways more beautiful and impactful than the original.

“There is really nothing that matches the tactile feeling of ink on paper,” he continued. “The relationship is so much more visceral than looking at a computer screen or smartphone. Running my hands over the sheet and feeling the impressions of the letterforms — just as I had done as a child in 1967 — was just so exciting. And knowing how much work went into that single sheet of paper made it all the more meaningful.”

Ganz has always had a love and appreciation for design, printing, history, archaeology and the modern miracle of the establishment of the state of Israel. All of those interests converged into one with this project, and it allowed him to step back in time and connect to what that exciting day must have felt like 75 years ago.

He shared a parting and personal thought. “This paper — and the famous Bar Kochba coins — represent the bookends of the exile. Those coins were one of the last known expressions of Jewish sovereignty in antiquity and were minted in 135 CE. This newspaper, printed 1,813 years later, was one of the first expressions of Jewish sovereignty of the newly established State. It will always have a special place in my heart.”

Am Yisrael Chai.

A limited number of sheets were hand printed and certified, and are available to those who would like to frame and display a most momentous day in Jewish history. For more information, visit www.state-of-israel-is-born.com.

By Yaffa Sacks