So much mail now was received in Whitwell that the mail carrier could not handle the deluge of envelopes and packages and asked the school to pick up the mail at the post office. So many clips arrived now that the students were unable to keep up with the counting and had to ask the parents to help.

In Washington the Schröders were receiving letters and clips as well. They loaded them into their car and drove them to Whitwell. They were greeted with joy and the announcement that they had collected 5 million clips and needed just 1 million more to reach their goal.

When asked what they should do if they get more than 6 million, the Schröders replied, keep collecting. The Nazis didn’t only kill the Jews, they killed many others as well. There were actually 11 million victims.

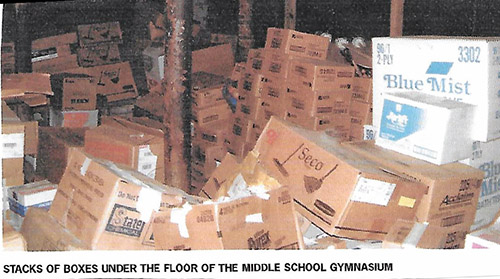

The clips kept coming until the school looked more like a warehouse than a school. They filled classroom, closets, the cafeteria, the gymnasium; they were everywhere. It was becoming a fire hazard.

What to do now? During a dinner of the Schröders and the Hoopers they considered various options about how to create a dignified memorial to those murdered. In their visit to the Holocaust Memorial in Washington they all had walked through the cattle car the Nazis had used to transport prisoners to concentration camps.

That was it! They needed to find such a cattle car and use it to store the paperclips as a memorial.

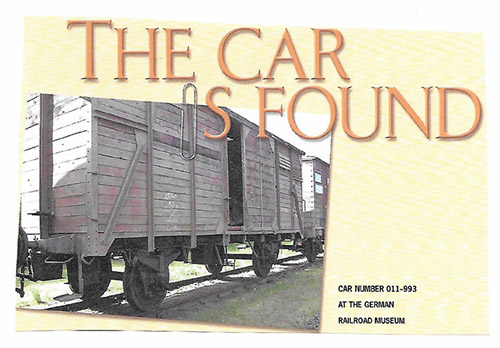

The idea was excellent, but where to find such a cattle car now so many years after the war? They wrote to Chancellor Gerhard Schröder (no relation) but he replied he could not help. The head of the Deutsche Reichsbahn, who had made millions under the Nazis transporting prisoners, replied that there were no Güterwagen (boxcars) left. The Schröders went to Germany and traveled 2000 miles through Europe but the only cars they found were built after the war. They were just about to give up when they received a phone call from a good friend, Prof. Klaus Hübotter, saying that his family had found what they were seeking. A small railroad museum north of Berlin owns a cattle car from the time of the Nazis.

The bad news was that the director of the museum declared the car not for sale. They drove 500 miles to meet with the director and then another 60 miles to the museum.

And then they saw it among other types of cars, foreign and domestic, new and old.

Car Number 011-993, built in 1917, looked just like they had seen in other pictures of the type used by the Nazis to transport prisoners. The history of the car showed that it seemingly had been abandoned by the Nazis in 1945 at the Polish town of Sibibor, very near one of the major Nazi extermination camps.

The director said he could not sell the car since it could not be replaced. But he was finally convinced after pleading by the Schröders and he agreed to sell the car “for whatever he had paid for it.”

Now to find a suitable place in Whitwell and build a memorial there when no one had an idea how to do it. The whole town came together and exchanged ideas. Carpenters, electricians, landscapers and anyone handy with tools pitched in with ideas and available work hours. An independent film company requested permission to come and film a documentary.

With financial help from friends, the Schröders were able to purchase the car. Now how to transport it 5000 miles to Whitwell? First it had to get to the nearest seaport by German rail. The German rail company was eager to help but said it would cost about $10,000. When told it was for the museum the kids were building, the cost disappeared as a gesture of goodwill.

While waiting for the problems to be solved the Schröders decided that the car needed to be dressed up with a sign before it got to the US. Local sign makers made two signs, one in German on one side of the car and one in English on the other side: “The Children’s Holocaust Memorial.”

Now came the technical problems. The car on a flatbed railroad was too high and would hit the overhead electric cables. The railroad technicians inspected the car and decided that it roll on its own wheels with some adjustments, provided the train goes no faster than 30 miles an hour. The railroad supplied a special locomotive and a brake car behind since they did not trust the brakes on the old car, and it started out on the 300-mile journey to Cuxhaven on the North Sea after extensive send-off coverage by newspaper, TV and radio.

(To be continued next week)

By Norbert Strauss

Norbert Strauss is a Teaneck resident and Englewood Hospital volunteer. He frequently speaks to groups to relay his family’s escape from Nazi Germany in 1941.