(Continued from last week)

The train had to stop every 30 miles to grease the old axles and to let faster trains go by. In Cuxhaven, in order to comply with U.S. Department of Agriculture regulations against a wood-eating bug, the car had to be sprayed with a disinfectant.

Back in Whitwell, Holocaust survivors from New York who had heard of the project came to visit and were received by teachers, students and residents in a packed audience. The four survivors shared their survival story with the audience. The students who had never seen a Jew were in tears and they hugged and kissed each other while it all was being recorded by the film crew.

In Cuxhaven, the Schröders were stunned when they saw the vessel that was going to transport the car to the U.S. It was the M/S Blue Sky, with Bergen as its home port. The story had started in Norway with the invention of the paperclip, then the anti-Nazi demonstration by the Norwegian population using paperclips and now a Norwegian ship would transport the car to the U.S. By the way, at just about the same time, the Norwegian Postal Service issued a commemorative stamp honoring Johan Vaaler, the inventor of the paperclip.

The Cuxhaven harbormaster ordered all work in the port to cease while the car was being loaded on board and being secured. The longshoremen removed their hats and military personnel saluted. The last person to come aboard was a high-ranking German army officer whose sole responsibility was to be concerned over the car.

Although the voyage started out in good weather, after a few days the ship was hit by a violent storm with 30-foot waves. The crew had secured everything and was hoping for the best. The captain stayed at the wheel for six hours, and the sea was calm again.

But a little while later mechanical trouble hit the vessel, when the main oil pump blew. The Blue Sky was dead in the water. The crew was able to make repairs and 20 hours later the ship arrived in Baltimore. The Coast Guard came on board since the Blue Sky had no certificate, never having gone to the U.S. before, but everything was approved by them.

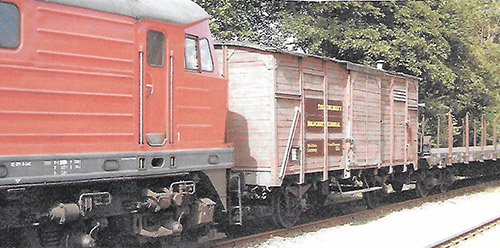

It was on September 9, 2001, that the railcar was off-loaded and put on a flat-bed railroad car of the CSX company, who had agreed to transport the car free of charge to Whitwell. Two days later, and it was September 11, 2001, the last leg of the trip started. As the car symbolizing tolerance travelled through the U.S. countryside, terrorists struck in New York, Washington and Pennsylvania.

While the car was on its way to Tennessee, railroad workers from the CSX company came with trucks and bulldozers to prepare the site. They had purchased the oldest tracks they could find, manufactured in 1947, the year many Jews were still being processed in European displaced person camps.

In Chattanooga the railroad car had been transferred to a big truck for the trip over the mountains to Whitwell accompanied by police cars with flashing lights. Finally, a crane lifted the car onto its tracks amongst the loud cheers of the whole town, which had assembled for the occasion. And then the students, with tears in their eyes, came to touch the car.

Car Number 001-993 had arrived.

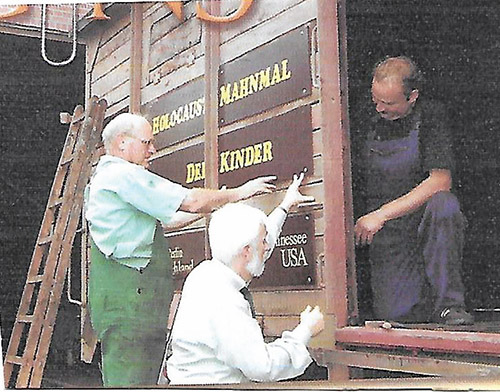

A lumber company donated lumber for a ramp up to the entrance of the car so that handicapped visitors could enter. Inside, the students arranged the 11 million clips behind two glass partitions on either side of the car. Residents dug up flowers and plants from their own property and replanted them around the railroad car.

November 9, 2001, the anniversary of the Kristallnacht, was going to be the official dedication. The town of 1600 had 2000 people that day. The Schröders were there with a collection of small stones collected in Germany to place on the memorial in accordance with the traditional gravesite custom. School and community leaders spoke and the University of Chattanooga orchestra played and their choir sang. Prayers were delivered by various religious denominations. Students from the Atlanta Jewish Day School said Kaddish.

When the ceremony was over, everyone slowly walked up the ramps to the open doors of the car to view the huge number of paperclips.

Over the years many schools and other groups from all over have visited the site. My grandson Rabbi Ari Perl, with his whole family, visited the museum a few years ago on one of their car trips from Dallas to New Jersey.

I met the principal, Mrs. Linda Hooper, a few years ago in Teaneck when she came to lecture to an audience about what her students had done.

The students had accomplished what they had set out to do despite great difficulties. The Schröders and others who helped in this task should also be complimented for their effort.

By Norbert Strauss

�