Last Wednesday, the last official day of winter, an excited group of Ruach participants gathered at Young Israel of New Rochelle for a captivating presentation by Elana Kaplan, a museum educator at both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Derfner Judaica Museum. Hosted by the Ruach program, the lecture offered an hour-long exploration of winter through the eyes of diverse artists across different cultures and eras. Through a carefully curated slideshow, Kaplan led the audience on a visual journey, showcasing how various artists captured the beauty and essence of the coldest season.

Eugene Wilk, a dedicated Ruach volunteer, introduced Kaplan, warmly welcoming her back to YINR. “She works at the Met and she brings the Met to us, instead of us having to go to the Metropolitan!”

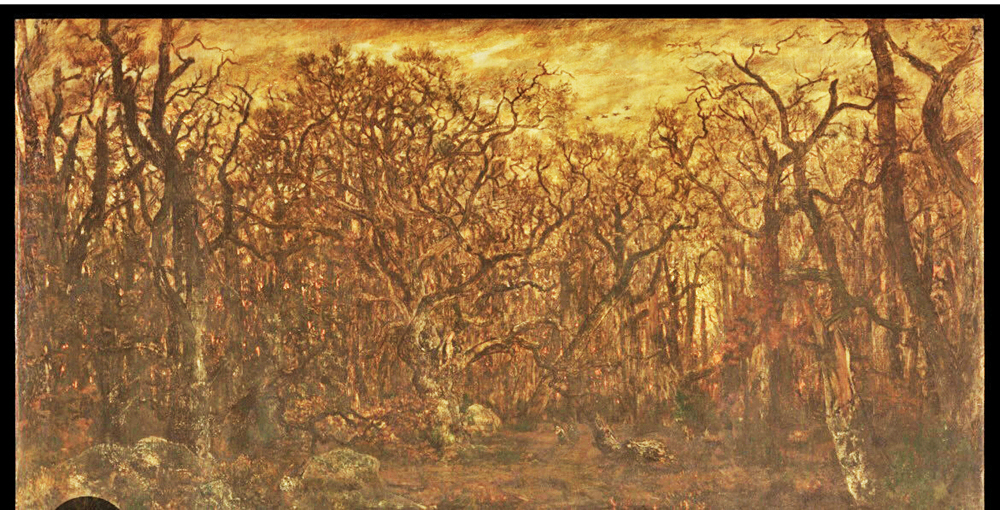

Kaplan opened her talk by noting the bare, wintry trees visible through the large windows of the synagogue, a fitting backdrop for the day’s discussion. She then introduced the first painting of the presentation: “The Forest in Winter at Sunset” by Théodore Rousseau. This dark and striking landscape, a centerpiece of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, had long fascinated Kaplan, who admitted to having spent hours sitting in front of it. The painting, which Rousseau worked on for 20 years, depicts the Forest of Fontainebleau, a site just outside of Paris. Despite the time he spent working on it, he never considered the piece finished—it remained in his studio with his unfinished paintings until his death.

Rousseau, a passionate advocate for nature, was one of the first artists to champion outdoor painting, immersing himself in the forests he depicted. He painted in all seasons, including the harsh winter. He was deeply troubled by the encroachment of tourism and commercialization on the pristine landscapes that he adored. His concerns led him to appeal directly to Emperor Napoleon III, successfully securing protection for the trees of Fontainebleau. His painting reflects this reverence for nature—the towering, intertwined branches dominate the composition, dwarfing the tiny human figures at the bottom. Birds flutter among the branches, and flecks of red and orange hint at the reflection of a winter sunset on pools of water. Rousseau’s painstaking attention to detail, constantly adding and altering branches over the years, imbues the painting with an intense and foreboding energy.

Shifting to a different approach to winter, Kaplan next introduced an impressionist masterpiece, “The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning,” by Camille Pissarro. She explained that Pissarro, the only Jewish Impressionist painter, was named Jacob Abraham Camille Pissarro, and grew up in the Jewish community of St. Thomas, a significant Jewish community at that time. As she guided the audience through his work, she provided context for the Impressionist movement itself—a radical departure from the classical art of the time. Unlike their predecessors, who focused on religious and historical themes, the Impressionists sought to capture moments of everyday life, emphasizing light, movement and atmosphere. Their technique—characterized by visible brushstrokes, open compositions and a preference for painting outdoors—was revolutionary.

Pissarro, often called the “Father of French Impressionism,” initially painted tranquil countryside scenes but later shifted to depicting urban life. His Boulevard Montmartre series, comprising 14 paintings, was created from a hotel room with a bird’s-eye view of the bustling Parisian streets. He meticulously painted the boulevard in different seasons and times of day, documenting how shifting light and weather transformed the scene.

Kaplan pointed out that Pissarro began this ambitious series at age 66, despite suffering from a chronic eye infection that made outdoor painting difficult. Instead, he adapted, painting from indoors while observing the world through a window. His decision was partially inspired by Monet’s highly successful “Haystack” series, which demonstrated the commercial potential of capturing the same subject under varying conditions.

In “The Boulevard Montmartre on a Winter Morning,” Pissarro conveys the essence of winter not through excessive detail but through atmosphere and mood. A delicate dusting of snow blankets the street, while the barren trees and soft, muted colors evoke the chill of a crisp winter day. The characteristic short, broken brushstrokes of Impressionism lend the painting a sense of movement, as if the city is alive with the gentle bustle of morning activity. This work is widely considered one of Pissarro’s most significant contributions to the Impressionist movement.

Throughout her lecture, Kaplan continued to unveil a variety of winter scenes, each offering a unique perspective on the season. She examined artists who were celebrated in their time and others who gained recognition posthumously, always contextualizing their work within their historical and cultural backgrounds. With each painting, she provided insight into the artist’s process, inspirations and techniques, enriching the audience’s understanding of both art and history.

The attentive audience, captivated by Kaplan’s depth of knowledge and engaging storytelling, left the event with a newfound appreciation for the many ways artists have interpreted winter’s beauty.