As we face another Memorial Day, I recall visiting with three old friends, a few years back, at a park in the nation’s capital. It seems like only yesterday that we were all together, but actually it has been many, many years. There was a crowd at the park that day, and it took us a while to connect, but with the aid of a book we made it. I found Harry, Bruce, and Paul. In 1970-72 we were gung-ho young fighter pilots on America and Constellation off the coast of Vietnam—the cream of the crop of the U.S. Navy, flying F-4J Phantoms. Now their names are on that 500-foot-long Vietnam War Memorial.

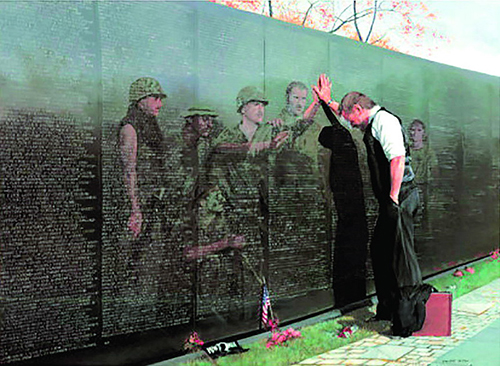

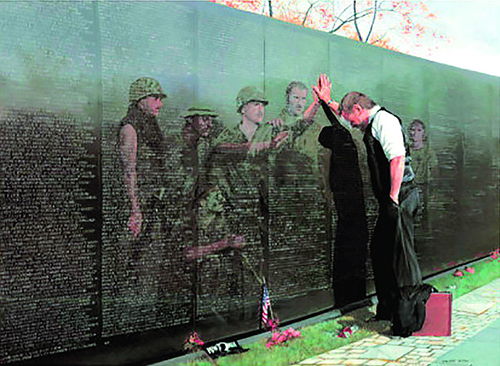

I am hesitant to visit the wall when I’m in Washington, DC because I don’t trust myself to keep my composure. Standing in front of that somber wall, I try to keep it light, reminiscing about how things were back then. We used to joke about our passionate love affair with an inanimate flying object we flew. We marveled at the thought that we actually got paid to do it. We were not draftees but college graduates in Vietnam by choice, opting for the cramped confines of a jet fighter cockpit over the comfort of corporate America. In all my life I’ve never been so passionate about any other work. If that sounds like an exaggeration, then you’ve never danced the wild blue with a supersonic angel.

To fight for your country is an honor. I vividly remember leaving my family and friends in San Diego headed for Vietnam. I wondered if I would live to see them again. For reasons I still don’t understand, I was fortunate to return while others did not.

Once in Vietnam, we passed the long, lonely hours in Alert 5, the ready room, our staterooms, or the Cubi O’Club. The complaint heard most often, in the standard gallows humor of a combat squadron, was, “It’s a lousy war, but it’s the only one we have.” (I’ve cleaned up the language a bit.) We sang mostly raunchy songs that never seemed to end—someone was always writing new verses—and, as an antidote to loneliness, fear in the night, and the sadness over dead friends, we often drank too much.

At the wall, I tell the guys only about the good parts of the years since we’ve been apart. I talk of those who went on to command squadrons, those who made captain and flag rank. I ask them if they’ve seen some other squadron mates who have joined them. I don’t tell them about how ostracized Vietnam vets still are. I don’t relate how the media had implied we Vietnam vets were, to quote one syndicated columnist, “either suckers or psychos, victims or monsters.” I don’t tell them that Hanoi Jane, who shot at us and helped torture our POWs, had married one of the richest guys in the United States. I don’t tell them that the secretary of defense they fought for back then has now declared that he was not a believer in the cause for which he assigned them all to their destiny. I don’t tell them that our commander-in-chief avoided serving while they were fighting and dying. And I don’t tell them we “lost” that lousy war. I give them the same story I’ve used for years: We were winning when I left.

I relive that final day as I stare at the black onyx wall. After 297 combat missions, we were leaving the South China Sea…heading east. The excitement of that day was only exceeded by coming into the break at Miramar, knowing that my wife, my two boys, my parents and other friends and family were waiting to welcome me home.

I was not the only one talking to the wall through tears. Folks in fatigues, leather vests, motorcycle jackets, and flight jackets lined the wall talking to friends. I backed about 25 yards away from the wall and sat down on the grass under a clear blue sky and midday sun that perfectly matched the tropical weather of the war zone. The wall, with all 58,200 names, consumed my field of vision. I tried to wrap my mind around the violence, carnage, and ruined lives that it represented. Then I thought of how Vietnam was only one small war in the history of the human race. I was overwhelmed with a sense of mankind’s wickedness balanced against some men and women’s willingness to serve.

Before becoming a spectacle in the park, I got up and walked back up to the wall to say goodbye and ran my fingers over the engraved names of my friends as if I could communicate with them through some kind of spiritual touch. I wanted them to know that God, duty, honor, and country will always remain the noblest calling. Revisionist histories from elite draft dodgers trying to justify and rationalize their own actions will never change that. I believe I have been a productive member of society since the day I left Vietnam. I am honored to have served there, and I am especially proud of my friends—heroes who voluntarily, enthusiastically gave their all. They demonstrated no greater love to a nation whose highbrow opinion makers are still trying to disavow them. May their names, indelibly engraved on that memorial wall, likewise be remembered on Memorial Day.

From an F-4 pilot: