I was standing in the middle of a boisterous kiddush lunch a few months after my 27-year-old son Ethan died of a drug overdose. As I scanned the room for a place to sit—I was after a table with people who didn’t know me—someone who’d been at the shiva approached and asked how I was. I did an appraisal to see if he was interested or was just asking, then said flatly, “I’m OK,” signaling I wasn’t. Since the shiva, I’d tried to sort out how to answer that question. Do I avoid making myself and others uncomfortable by saying I’m OK? And If I say I’m OK, would people think I am an uncaring father?

As I broke off eye contact, the shiva goer dropped his hand on my shoulder and reminded me of a conversation I had with my son the night before he died. I’d forgotten I’d told this story and hearing the words from him now was jarring. I’d shared this at the shiva to sell myself on having been a good father. And this person was reminding me now for the same reason, but I wasn’t up for hearing it. After a moment, he motioned off to an imaginary horizon and said, “So, the shiva’s over. You’re still back there and everyone is here. You’re in the same place but everyone else has gone on without you.”

A few weeks later, I was introduced to Susan Zilberman, who’d been renting a summer home in Atlantic Beach, New York, where I was staying after my son’s shiva. She’d started a Manhattan chapter of GRASP (Grief Recovery After Substance Passing), after her 26-year-old son Gregg overdosed nine years earlier.

These support group meetings are a kind of demilitarized zone insulating us from what we see as a quietly critical outside world and from ourselves. In the group, we can say out loud what we can’t outside of it. We can talk about the oppressive feelings we have of failure and self blame and for some, the conflicting emotions of relief following a death. And the paralyzing guilt for feeling that relief. The din of silence following life with an addict is impossible to navigate. I, like others in our group, do not want to be told I did everything I could because this guilt is how we punish ourselves. Many of us need to suffer for a crime. The well-intentioned outside world wants to free us from that guilt. But many of us prefer you lock the cell door and throw away the key, while others would rather you throw away the cell. We parents, and other family members fell down on the job. We were expected to keep our people alive; our one job. That they are gone, is the smoking gun.

I found my son’s body in the bathroom of our Jerusalem hotel room late at night after coming back from a long work day. He’d texted me in the afternoon asking if I’d needed anything at the store. I sat on the edge of the bed, the hotel room flooded with police, first responders and IDF officials. A fleeting thought of stepping off the balcony and disappearing was dissolved by the two policemen standing sentry there. A young woman approached me and after tripping over my son’s body she gently let me know he was gone, a reality I’d been aware of for hours. I’d tried to resuscitate his then cold and stiff body which I’d dragged from the bathroom. It hadn’t occurred to me until the next day that foul play had been considered. It was while I sat in a Jerusalem courtroom as the IDF argued for an autopsy and my lawyer argued against it.

In the almost six years since my son’s death, I’ve learned a lot about addiction. That education, for most, comes in the days after a loved one’s passing. I came to understand how powerful a force substance abuse can be. An addict likened it to starving for food. It’s not clear why some are able to escape the gravitational force of addiction, while others succumb. It is clear though, that many struggled with mental health. Doctors and hospitals, with the best intentions, aren’t able to treat mental illnesses in the one to three days allowed by medical insurance. Rehabs have a notoriously low success rate along with medication, tough love, interventions and unconditional love. Addiction isn’t a character flaw or a lack of self discipline, and expectations that the addict just abstain rarely amount to much. Even after stopping drug use, addicts don’t fall off a wagon like alcoholics—they fall off a cliff. They spend their lives walking along a knife’s edge. The drug user who dies after relapsing just once is typical. And in the age of fentanyl poisoning, the chances of survival are even lower.

Through this all, I’ve also come to understand the isolation brought about by grief, and especially by grief after losing a loved one to addiction. We talk about the feelings of loneliness and the power of guilt and shame. Many of us unwittingly colluded with our addicted loved ones. We wanted to believe their denials. Our need for hope and self protection rivaled their need for drugs. Our addicted loved ones told us what we wanted to hear so they could keep a distance from their own deep shame and despair. We sometimes disengaged from the pain of waiting for the other shoe to drop.

For those of us managing shame, we often look for detours around the intersection of the dimly lit unpaved roads we keep to and the well marked eight lane highway with gleaming lives, successful college bound children, weddings and brisim. My son Ethan struggled to keep to any sort of path. In the many years before he passed I dreaded questions like, “So what college is your son going to?” I was at times bitterly jealous of parents who could tell success stories about their children and have worked hard to rearrange those feelings. I still ruminate on what if I’d done this or that.

Every now and again I hear myself enumerating the difficult times with my son’s addiction. There was a call around midnight bringing me to a New Jersey hospital where I waited for my son to wake up. Another to a Long Island hospital. Driving him home with one hand on the steering wheel and the other trying to keep him in the car. And towards the end of his life, coming to Jerusalem after he’d passed out in the street there. As I hear myself tell these stories I know I’m asking to be found innocent of my crimes. But that verdict I can only get from others and not from myself.

The night of my son’s death, after the room emptied, I sat alone with a Hatzolah member who was kind enough to not interrupt the stream of invectives I pointed at myself. Later, long into the early morning hours, I turned to asking the first responder how I would tell my son’s sister and his mother. How could I tell them I’d failed to keep Ethan alive. Eventually, as the sun rose, two members of an IDF unit for family support arrived followed by a friend.

Ernest Hemingway said “Every man has two deaths, when he is buried in the ground and the last time someone says his name.” What is unusual about families with addiction, is that grieving and trauma often begin long before the physical loss. We mourn the disappearance of a relationship. I remember standing in a Jerusalem street looking forward to seeing my son. It was a Friday evening as the day settled into Shabbat. Watching people stream past on their way to the Old City I noticed a middle aged father and son walking together. There was nothing remarkable about them—no smiles or chatting, just a father and son. As they passed by, a wave of profound sadness rose in me because it was a relationship for which I’d been desperate.

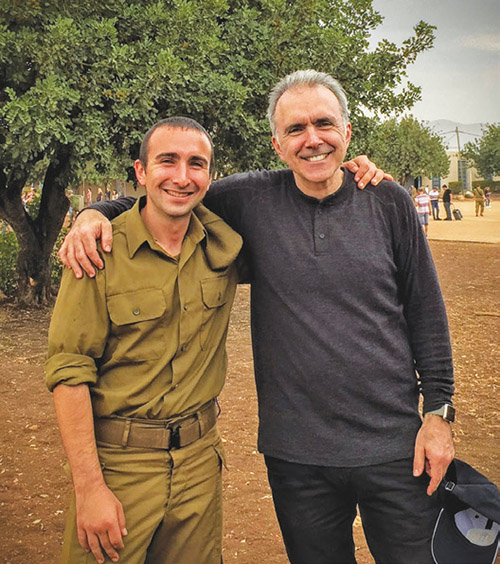

The night before my son died he told me about an accomplishment of his. Something we would both be proud of. Ethan and I were staying in a Jerusalem hotel together and had just gotten into bed. Nearly two years before that night the two of us were heading north from Tel Aviv along the Jordan Valley toward his new kibbutz and home for the next year. As we drove into the night, we talked about self worth. He told me he had trouble finding value in himself and wasn’t able to find his place in the world. It was at once heart-rending and a painful indictment of me as a father. I let him know he needed to find that thing. That he’d need to manage that himself. I knew I couldn’t give it to him. When the two of us arrived at the kibbutz we were warmly greeted by people and a community he’d formed a bond with, and I was once again hopeful. I spent a few Shabbats with my son there over the next year and it was a good year for both of us.

Now, as my son and I lay in the dark hotel room he said, “Dad, I did what you told me to do. I’ve been thinking about what I like about myself.” He went on to tell me how on the kibbutz he’d helped a girl who wanted to be a long distance runner. A runner himself, my son encouraged the girl, coached her and helped her grow and find her own value. That girl later invited me to run in the Jerusalem Marathon with a team memorializing my son.

The morning after Ethan died, two of his friends, having been notified by the IDF, appeared in my hotel room. They told stories about Ethan’s sense of humor, his empathy and his role as the older brother to a group of soldiers who roomed together. Ethan was someone they could confide in and who they cared about. It was a glimpse of a person I hadn’t seen. I began to realize that I hadn’t made the effort to see my son for who he was because I was otherwise occupied by resentment towards him for not giving me the son I wanted.

Now each week, when a group of us meet, we think the unthinkable and speak the unspeakable. And for many, the unspeakable is not that we have suffered a great loss. The unspeakable is that we in some way were complicit. On each of those evenings, we feel less alone and I give others the same advice I gave to my son. Find the value in yourself and remember all of the ways you helped and loved your child. Think about what you did and not about what you didn’t do. And then, on some nights, while I’m lying in the dark alone waiting for sleep, I give the advice to myself.

Gary Magder works in digital marketing for the OU. For the past four years he’s facilitated a bereavement group for people who have lost loved ones to substance abuse, the Manhattan chapter of Grasp. If you or someone you know has lost a loved one from addiction and would like to attend a meeting please contact [email protected] or call 917 696 6517.*