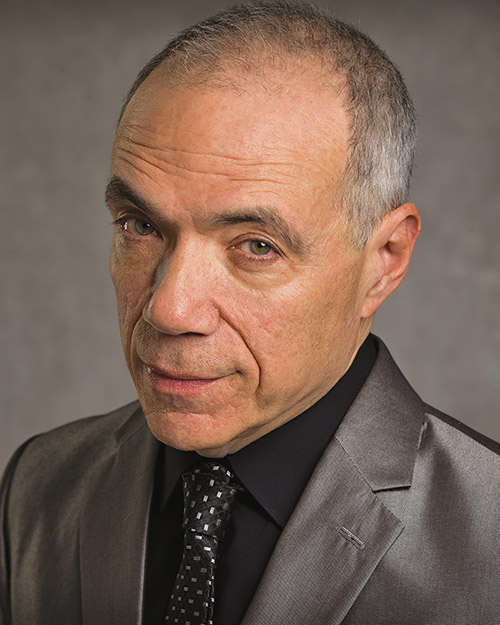

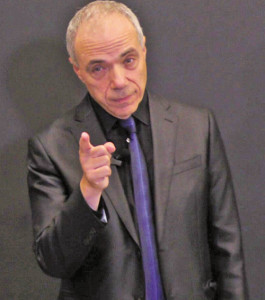

Michael Takiff is a quintessential Renaissance man—honors Yale graduate, standup comic, classical singer, presidential biographer and oral historian, whose true passion is acting. Despite pre-show stage jitters and self-doubt endemic to most performers, he knows, once onstage, that “This is where I belong.” Perhaps that helps explain why, in off-Broadway’s “Jews, God, and History (Not Necessarily in That Order),” through June 5 at Manhattan’s Siggy Theater at the Flea, he not only writes but performs his own work.

There’s much more to the man, and a more complex tapestry to his Judaism, than the show reveals. Takiff, although not Orthodox in practice, is no stranger to Orthodoxy. A highly thoughtful man, his connection to Judaism is through history, tradition, and outlook. He is a direct descendant of Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev, and his devout father’s family was traditional (his mother, of Workmen’s Circle stock, attended Yiddish, not Hebrew school).

In Elmora, Elizabeth, his parents and siblings lived comfortably but not lavishly, with family summers at Bradley (“Bagel”) Beach. This represented stability, something that his father (lawyer for a chemical company) and mother (music teacher/homemaker), lacked during their own Depression childhoods.

Jewish life for Takiff included accompanying his father to JEC for the High Holy Days and other major holidays. His mother attended because of his father, who also said Kaddish for her mother. The JEC’s Rabbi Pinchas Teitz, z”l already had a strong connection to Takiff’s family, visited his maternal grandparents’ furniture store in downtown Elizabeth, and had weighty discussions about Judaism with Takiff’s grandmother, an atheist. When she passed, Rabbi Teitz conducted the funeral. Clearly, he made a strong impression on Takiff; the longest scene in the show is a recollection of Yom Kippur at the JEC.

There are also memories of his family life built into the dialogue, music, dance, and nostalgia of his other one-man show, Black Tie: A Son’s Journey through the Death and Life of His Father, performed pre-pandemic. It characterizes his father both as straight arrow “company man” and as soldier whose end-of-life revelations cast him in a vastly different light.

Takiff’s path to theater was somewhat circuitous. His father hoped for a lawyer son, and at Yale, he majored in history. When he graduated, he told himself, “I’m done with this.” Successes in school plays bolstered his confidence, and New York bound, he acted, trained in classical voice, and booked standup comedy gigs. Undaunted by career slumps, he found new vistas.

To pay his bills, Takiff worked in transcription and word processing, which piqued his interest in writing. He had always been, and still is, a Mets fan, and one day, duly upset about the installation of astro turf in their stadium, he wrote Pseudo Turf at Shea? No Hit and a Big Error. Somehow, the article surfaced as an op-ed in the New York Times (1984, April 28). After this, he enrolled in writing courses, was briefly a “ghost writer,” and established his literary reputation by prolifically publishing about politics and war.

Takiff’s extensive knowledge of both genres is evident in his critically acclaimed biography, A Complicated Man: The Life of Bill Clinton, published, ironically, by Yale University Press. His second book resonated closer to home. His father’s wartime experiences factored heavily into Brave Men, Gentle Heroes: American Fathers and Sons in World War II and Vietnam, published by HarperCollins and a Washington Post “Critics Pick.” For the latter book, Takiff traveled cross-country to interview fathers and sons who served in both wars. In addition, he founded and is Executive Director of Gravitas History, a company that helps people record family legacies, using extensive documentation gathered through oral histories.

Here’s where our conversation turns less biographical and more philosophical: Jewish identity, writ large. For Takiff, it’s something you can’t escape, even if you try. “It’s part of who you are.” Many Jews think this is “the second Land of Milk and Honey, the New Jerusalem… “I don’t think we are going to be fully comfortable.” When he assesses American Judaism through the lens of his immigrant grandmother, he asks, “ Where have Jews not only been free to practice religion but to excel in so many walks of life?” His grandmother was relieved not to dread the “knock at the door, pogroms, the SS … to go to synagogue and not fear marauding bands coming to break it up … and then Pittsburgh happened.”

Although such incidents are isolated, there is “a lot of hate going on here,” with emergent racism. He feels that “Sooner or later, it will come around to Jews … Charlottesville, ‘Jews will not replace us,’ Protocols of Zion, blood libel … I don’t know about our place in this country. I’m old enough that I’ll probably be OK, but my son—he’s 23—what’s his future in this country? Living in the Upper West Side … this is a very tolerant area … It’s not like that everywhere else.” As antisemitism waxes and wanes, he says, the Jews’ position in society is anomalous “… always looking around the corner for the next persecutor … especially with the things people say today … very conscious of being Jewish today in this country … the fragility of it … what it means and how to navigate it.”

Takiff quotes Mel Brooks: “Comedy is tragedy plus time” and adds that it’s how we process our tragic history, joking about everything, including our persecutors. “There is little that is off limits for jokes in terms of our history” and he addresses this in Jews, God, and History. Jews have much to be proud of but how do we move forward knowing the tragic part? That’s essential to a.2% minority. You think we’d just shut up after a while, but we don’t, we just keep talking. That’s the great thing about us. After a while, it gets annoying. Enough already,” he jokes.

I ask about Jews’ lives abroad, but Takiff has neither lived elsewhere nor explored the matter in depth. Why stay so close to home? “They’d have to carry me out feet first,” he remarks. “I’m a New Yorker.” For Takiff and his wife, social worker Amy Winarsky, the Upper West Side is the “Jerusalem of cultural Jewry.” They raised their son, a musician, there.

The West Side’s Jews, like Takiff, vote as Democrats, as do 70%-75% of New York Jews. That’s counterintuitive because, if one correlates income level and voter preference, then the many professionally successful American Jews should vote Republican. But they don’t.

It’s our history, he posits. “Minorities are sensitive to the needs of other minorities … the lessons I take from being Jewish,” he says, pointing to freedoms underscored in the Haggadah. “When Moses says, ‘Let my people go,’ he doesn’t say, ‘Let my people pay a lower capital gains tax.’” To Takiff, it means freedom and liberation from exploitation. That informs his politics, as a Jew within the liberal, Democratic West Side shtetl. In the Haggadah, “This is what the Almighty did to me with an outstretched arm” is “such a powerful idea.”

I challenge him to apply this globally, which he does, referencing US military intervention in WWII. “Who knows what would have happened? (Today) … Everything is complex and complicated by realities of power.” Thus, the reality of Ukraine’s horrific war—”Why put people through this suffering for no good reason? Why hold grudges (about Ukraine and Germany)? … It’s just not good for us.”

In our conversation, Takiff asks and answers many questions, injecting wry humor throughout. Similarly, he hopes that audiences will enjoy his show, but probe deeper “not just about Jews but about humans in modern society” living with ancient traditions and “how we look at God in the modern, post-Holocaust age.” After all, isn’t all the asking and answering, spiked with a measure of humor, and embedded in our DNA, what has sustained us over millennia?

Rachel Kovacs is an Adjunct Associate Professor of communication at CUNY, a PR professional, theater reviewer for offoffonline.com—and a Judaics teacher. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.