They were a determined group of young Jewish men who escaped mostly from Nazi Germany and Austria to the United Kingdom only to be recruited into a secret military troop whose daring exploits were crucial in helping the Allies secure victory during World War II.

Yet, the invaluable role the X Troop, as they were known, played by ensuring a successful landing on the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, obtaining vital intelligence that was also critical during the Nuremberg war crimes trials, skillfully interrogating and acting as highly trained commandos went virtually unknown until recently when Dr. Leah Garrett’s book about their daring exploits was published.

Garrett, the director of the Jewish Studies Center and of Hebrew and Jewish Studies at Hunter College in Manhattan, said the refugees, many of whom arrived as teenagers aboard the Kindertransport, were united in their hatred of Germans and the desire to rescue their families left behind.

“This was very personal for them,” said Garrett. “They knew the clock was ticking for their families… All were focused on the prize.”

She made her remarks during the annual Raoul Wallenberg program for Rutgers University’s Allen and Joan Bildner Center for the Study of Jewish Life. Held at the Douglass College Center in New Brunswick; it was its first in-person program since before the pandemic.

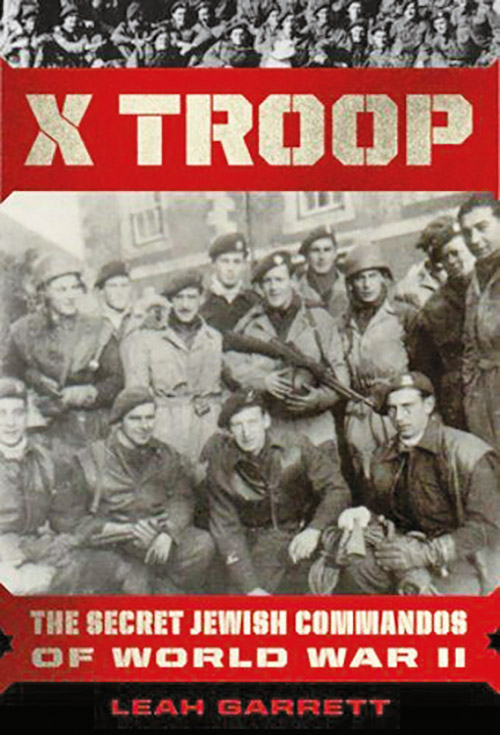

Garrett’s book, “X Troop: The Secret Jewish Commandos of World War II,” tells a chapter of war history that reveals the antisemitism the troopers were subjected to in Great Britain, where they were initially classified as “enemy aliens,” and the heroism displayed by them in standing up to the Nazis.

“They were truly a band of Jewish brothers,” said Garrett.

Britain had feared young German-Jewish men could be “a fifth column” and most were placed in internment camps behind barbed wire, much like Japanese-Americans were in the United States after Pearl Harbor, she explained. Some were sent on a horrific voyage to Australian internment camps where they were given rotten food and were subject to deplorable conditions by the antisemitic crew.

The book has become a bestseller in Great Britain, where it was serialized in the press and given extensive coverage on the BBC, said Garrett.

The idea to form the troop came from Lord Louis Mountbatten, head of the British Army’s Combined Operations Command, who suggested the unit to Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

“They selected the best and most brilliant,” said Garrett for the 87-man troop, all of whom took English names and identities, were sent to a Welch village for a year of rigorous training and to learn to minimize their accents and given Church of England documents for their own protection. They were then dispersed among the top fighting units of the British military.

“If they were captured and the Germans found out they were Jewish, they and their families left behind in Germany would be killed,” she explained, adding the men knew should they die in action, “they would be buried under a cross.”

The troop was unique among the elite fighting units in that they were trained both as military commandos and in counterintelligence, allowing them to use their German language proficiency to capture high-ranking officials, often interrogating Nazis on the battlefield itself, said Garrett. More than half were killed in action.

Garrett conducted interviews with the two surviving troop members—both of whom have since died—family members and gathered information from archival sources such as the Imperial War Museum, British war diaries and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM).

Many of their exploits were nothing short of feats of bravery and cunning.

Lt. Peter Masters, an artist from Vienna, volunteered to be part of the Bicycle Troop on D-Day, leading the charge ahead of British troops across Pegasus Bridge, spanning the Canen Canal deep behind enemy lines, at the onset of the invasion. On another occasion, he got two intelligence officers to give up the location of German positions on the outskirts of Wesel, thereby allowing the British to secure the Rhine crossing.

Lt. George Lane, the former Lanyi Gyorgy, was one of the only X troopers not from Germany or Austria. A former member of the Hungarian Olympic water polo team, he was sent by boat on D-Day to report if German land mines had the potential to thwart D-Day. After two dives, Lane confirmed they were standard Teller mines that had corroded in the water. Garrett said Lane’s information proved so invaluable that British military authorities credited him with ensuring the massive Allied invasion on the beaches of Normandy could go forward as planned.

On his third outing, Lane was captured and taken to a castle, where he was interrogated by none other than Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, infamous as the Desert Fox.

Lane was able to peek out of the corner of his blindfold while being driven to the castle, said Garrett, and was able to wire its location back to London. Shortly thereafter, Rommel’s car was hit. Lane was sent to a POW camp for British officers.

Lt. Manfred Gans, an Orthodox former engineering student then known as Fred Gray, also went ashore on Sword Beach on D-Day where he encountered a group of 25 German soldiers, who he interrogated in German to find the route through the minefields and lead his regiment to safety.

Perhaps one of the most daring escapades of the war belonged to Gans, whose parents had been in hiding, but had been captured and taken to Bergen-Belsen.

However, while in Germany in the final days of the war, he got a letter from the Red Cross informing him his parents were in Theresienstadt in Czechoslovakia. Garrett said because of his record of bravery and skill, Gans had gained the respect of his commanding officer.

“He went to his commanding officer and said, ‘I need a Jeep. I need to rescue my parents,’” said Garrett, according to his diary, now at the USHMM, and barreled through an “apocalyptic scene” of German, American and Russian checkpoints and rampaging villagers, arriving at Theresienstadt a day after its liberation by Russian troops.

“There is a typhoid epidemic, and he goes in and finds his parents,” said Garrett.

Gans would later go on to earn a graduate degree in chemical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and have a successful career. One of only several surviving troop members to revert back to their original name, Gans moved to Bergen County, living in Leonia for decades and serving as president of the former Congregation Sons of Israel. He died at his home in Fort Lee in 2010, but published his memoir shortly before his death.