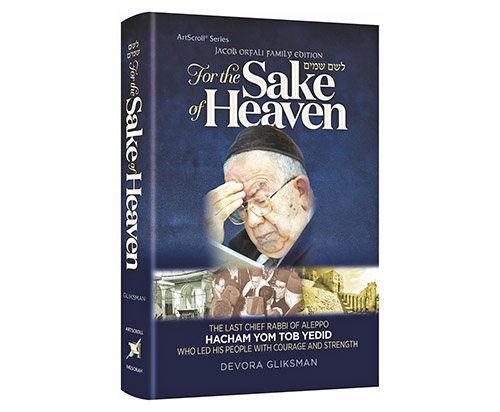

Highlighting: “For the Sake of Heaven” by Devorah Glicksman. Artscroll Shaar Press. 2022. Hardcover. English. 476 pages. ISBN #: 9781422631720.

(Courtesy of Artscroll) Hacham Yom Tob Yedid Halevi lived an epic life of courage and devotion through his decades as chief rabbi of the glorious Halab (Aleppo) community.

As the community’s leader during its last days, he courageously faced challenges, torture and threats. Amidst the confusion and turmoil, Hacham Yom Tob had the enormous responsibility of keeping his community devoted to Torah and tradition. And he accomplished the impossible: Halab remained as it had for centuries, a city where everyone kept Shabbat, prayed in the Bet Knesset, and stayed connected to Torah.

The following is an excerpt from his upcoming biography “For the Sake of Heaven,” written so powerfully by Devora Gliksman, to be published by ArtScroll Mesorah Publications next week:

Chapter 7

He Fears Hashem and Desires His Mitzvot

“Praiseworthy is the man…

who is careful not to transgress His commandments,

for he fears the Almighty… and he does His mitzvot,

from his heart’s desire,

not to appear ‘great’ in front of any man, and not for any reward,

but only for the Almighty, Who commanded him to do [His mitzvot].”

(Meir Tob, Tehillim 112:1)

“Abraham, what is the question of the Tosafot?” Hacham Yom Tob asked.

He nodded to Abraham’s answer and addressed Shlomo, “What does Tosafot answer?”

Around the table he continued, from talmid to talmid, sometimes helping a student, sometimes clarifying a new point, always gently, almost like a friend. Suddenly, a member of the Hebra Kaddisha walked into the room.

“Ezra passed away…”

Hacham Yom Tob nodded; this was not news.

“We are not going to bury him…”

Hacham Yom Tob looked at him impassively.

“We deserve the raise that we asked for …”

In an instant, Hacham Yom Tob understood the whole story. Mr. E. had recently passed away, leaving his modest wealth to the community. The Hebra Kaddisha wanted a share in that wealth, while he and Hacham Abraham Zaafrani had decided to allot the money differently. The Hebra Kaddisha was taking out their frustration on Ezra, a truly unfortunate person.

Ezra had learned in the Midrash. Then he became ill and lost his mind. He used to walk the streets of Halab barefoot, with tattered clothing, a shell of a human being. But when he came to the Midrash and the talmidim would ask him something in learning, he was always able to answer them. Even had he not been a talmid hacham, he deserved an honorable burial.

Hacham Yom Tob closed his sefer with a bang.

“You do not want to bury him? We will bury him!” he declared, standing up.

“Come!” he indicated to his talmidim, “We are going to take care of the niftar.”

The Holy Mitzva of Burying the Dead

Hashem commanded His people to bury a person who dies. If a person instructs his family not to “waste” inheritance money on his burial, his will is disregarded. Rather, the inheritors must pay for the burial (Shul’han Aruch, Yoreh Deah 348:2). If the deceased did not leave over any money for his burial, he is a met mitzvah. Whoever takes upon himself to bury this person for free earns a special reward. This is seen from David HaMelech’s praise of the people of Yavesh Gilad who buried Shaul HaMelech and his sons, whose bodies had been abandoned (II Shmuel 2:5-6).

Torah learning supersedes virtually every mitzva. However, the mitzva of accompanying a deceased on his last journey is so important, one stops learning Torah in order to perform this mitzva, even if the deceased is an unlearned person. For one who is learned, one stops learning Torah until there are 600,000 people in attendance (Shul’han Aruch, Yoreh Deah 361:1).

The whole group — minus the Kohanim — walked with Hacham Yom Tob out of the Midrash, to the entrance of the room where the tahara was supposed to take place. The Hacham turned to two talmidim. “You are going to help me.” Then he turned to several others. “And you are going to wait over here.”

Shlomo Zaafrani’s thoughts raced as he stood outside. I am only 20 years old… I don’t want to see a dead body! But Hacham Yom Tob instructed him to wait, so he waited. A little while later, Hacham Yom Tob emerged, his usually impeccable appearance altered by his rolled-up sleeves and pants.

So they should not get wet, assumed Shlomo. Just thinking about cleaning a dead man’s body made him queasy. But looking at the Chief Rabbi of Halab — the most respected Jew in the city — quietly triumphant, after having done the greatest kindness for a poor, mentally unstable man, was inordinately moving. Shlomo was proud to be his student.

Hacham Yom Tob pointed to two of his talmidim.

“Go inside. The niftar is on the mittah. We are going to escort him to his grave,” Hacham Yom Tob instructed. The talmidim emerged with the niftar, wrapped in his shrouds, on the stretcher. They carried the niftar as Hacham Yom Tob and the other talmidim accompanied them to the cemetery. They dug the grave. They buried the unfortunate man in an honorable fashion.

And we learned to have the courage to do what is right, reflected Shlomo Zaafrani.

News of the incident spread through Halab, arousing everyone’s passion.

“Our Hacham has to perform a tahara while the Hebra Kaddisha stands by?”

“What kind of community are we?”

“For a few grushim…?!”

The members of the Hebra Kaddisha were embarrassed, as was the community. But they were also impressed. What other community had a Hacham as courageous and compassionate as the Hacham of Halab?

Hacham Yom Tob was the community’s most powerful role model. His actions reflected his love for Hashem and His mitzvot and he expected all his people to share that reverence. You are coming to pray? Come before the minyan begins so that you can put on tefillin properly, find a siddur, open it to the necessary page. Don’t you appreciate the awesome privilege you are being given, the privilege of speaking to your Creator?

Hacham Yom Tob was always at his minyan at least 10 minutes before prayers, and he expected every Talmud Torah teacher to do the same. All men should do this, but certainly one who teaches Torah. And woe to the teacher who was even one minute late! Hacham Yom Tob would call him over that day. What kind of religious role model is a teacher who comes late to prayers? He would warn him once or twice, but if there was no improvement, he would fire a teacher for coming late to minyan.

Hacham Yom Tob conveyed to his people: We are a G-d fearing community. We learn His Torah. We do His mitzvot. We serve Him with love and awe.

VWX

Over the years, there was a growing sense outside Syria that Syrian Jews were being oppressed. This was both true and false. When the political climate was quiet, there was nothing “bad” about life in Syria. The main problem was that Syrian Jews lived in a cage. Whatever the Halabim knew about Israel or America, or about progress in the modern world, was whatever they managed to secretly hear on Kol Yisrael. Very few people had phones. Those who did, knew that the operator listened to their conversations. A censor opened every piece of mail. Every newspaper was screened, as was every news program on the radio or television. Halabi Jews were stifled by the knowledge that they knew nothing beyond what the government allowed them to know.

But, on a day-to-day basis, people were satisfied with their lives. Syrian mentality was easygoing, unpressured. Everyone had their schedules and duties, but they also had time to enjoy each other’s company, to sit outside in a park and talk and laugh and just be.

Even the poor had their basic needs. And those who were rich could not live much differently than the poor. A rich man might travel more often, because he had money to bribe the right people, but there were few places to go, few ways for a person to flaunt his wealth.

Yet, as is human nature, people found ways.

Weddings in Halab had always been very simple. The bride was escorted by her friends and family from her home, and the groom was escorted from his, until they reached the K’nees. The Hacham performed the ceremony, there were a few minutes of dancing and singing, m’labas was distributed to the crowds, and then everyone escorted the groom and bride to their wedding feast to which only close family was invited.

As the Syrian economy improved, people began earning more money.1

Suddenly there were more lavish engagements and weddings, with large flower arrangements being sent to the bride, more elaborate refreshments distributed in the K’nees, and many people invited to the wedding feast. Then, after the wedding feast, the friends of the new couple would escort them through the streets of Jamilieh to their new home, singing and dancing and being altogether disruptive in the middle of the night.

Hacham Yom Tob never spent more than 10 minutes at a wedding.

“Don’t come for me until you are completely ready,” he would tell the fathers of the bride and groom. “Take all your pictures, do anything you want, then come for me.”

Hacham Yom Tob had no patience for idle chatter. He remained in his office, next to the Midrash, immersed in his learning, until he was called. Then he immediately closed his sefer and accompanied the two fathers and the groom to the K’nees or the Talmud Torah, downstairs. He performed the ceremony, Hacham Abraham Zaafrani recited all the berachot, Hacham Yom Tob wished everyone mabrook, and then he went back upstairs to learn.

He never attended a wedding feast, unless it was for close family. He certainly had no idea what was going on in the streets of Jamilieh in the wee hours of the morning.

As usual, he found out.

Shabbat, Hacham Yom Tob walked to the front of the K’nees.

Everyone stiffened. What new proclamation was he going to make?

“I have become aware of some new developments in our community,” he began. “They must stop immediately! Extravagant spending is wasteful, and arouses the jealousy of Jews and of non-Jews. Why would we want to do that? No one is allowed to send flowers to a bride other than the parents of the bride and groom. No one may spend more than what is appropriate. There will be no food served at a reception other than the m’labas and cookies that have always been served. At an engagement, only siblings of the bride and groom and twenty friends are allowed. The same applies to the wedding feast. And certainly, there should be no loud processions at night, as Yaakob Abinu said to his sons, ‘Why should others see us?’”2

With that Hacham Yom Tob stepped down.

Keeping a Low Profile

Moshe Rabbenu recalled that Hashem said to him, You have [traveled long] enough… turn north (Devarim 2:3). The Hebrew word for north is tzafona, which can also be translated as hidden. Hence, this verse can be read homiletically: “You have enough [material possessions]… turn and hide them!” (Devarim Rabbah 1:19).

Contrary to the “if you have it, flaunt it” custom of today, Judaism teaches, “If you have it, hide it” (Kli Yakar). Although anti-Semites don’t need an excuse to hate Jews, one of the triggers for anti-Semitism has historically been the success and wealth, either real or imagined, enjoyed by Jewish communities. While there is no justification for

anti-Semitism, flaunting luxury is simply not a Jewish trait.

After Shabbat, Hacham Yom Tob wrote up his takanot on a large placard for everyone to see. While some of the newly wealthy members of the community might have grumbled, overall, the community was relieved. Most Halabim managed financially, but barely. Every time the standards went up, they felt themselves choking. And the midnight parades rightfully worried the older generation; the young were too inexperienced to care.

Hacham Yom Tob disdained luxuries and extravagance. They lured people into lives of wastefulness and pleasure as opposed to Torah and mitzvot. He loved the poor. Without money to spend on foolishness, they were more likely to listen to a shiur, or to spend time saying Tehillim in the K’nees.

But his proclamation was to the whole community: This is not the way a Jew lives!

A Jew — even one who is wealthy — lives quietly, modestly, humbly.

Perhaps that explains his love for the people of Qamishli.3

VWX

Throughout the 1950s and 60s, whole families had relocated from Qamishli to Halab and were fully integrated into the Halabi community. Yet there were still many families who had homes and income in Qamishli and could not move. They sent their children to Halab because Hacham Yom Tob committed himself to taking care of them. As usual, these children arrived unable to read Hebrew.

“We used to put older boys into classes with little children,” Hacham Yom Tob told Abraham Zarif, “but I would rather not do that. It is embarrassing for them. You usually come to the K’nees at 2:00 to learn. Come at 1:00 instead. You will teach them privately, from 1:00 to 2:00 every day, and you will get paid, per session, from the kehillah.”

Abraham agreed. After a few days, he noticed that every day Hacham Yom Tob showed up, looking at his watch, at precisely 1:00.

Okay, Abraham noted, Hacham Yom Tob wants me to begin at exactly 1:00, not 1:10 or even 1:02. He wants me to know that I should not feel like I am doing anyone a favor, and therefore can be lax. Rather, I am fulfilling a holy obligation.

For the entire year that Abraham tutored these children, Hacham Yom Tob poked his head in at 1:00. Every so often, he would ask Abraham how they were doing. When Abraham felt that the boys knew how to pray properly, Hacham Yom Tob told him to begin teaching them Humash. When they reached the perashah that their age group was learning, Hacham Yom Tob tested them.

“Okay,” he told Abraham, “they can go into a regular class. Your job is over.”

Hacham Yom Tob was the Chief Rabbi. These were five little boys from poor homes. He could have assigned Abraham to teach them and then left the rest up to him. No one expected the Hacham to take personal interest. No one — except Abraham — knew how closely he followed through.

There was no one “on top” of Hacham Yom Tob. He did not have to report to anyone; everyone in the community had to report to him. Yet he operated with the clear recognition that he was reporting, every day, all day, to the only One Who mattered.

1. Hafez Assad changed Syria’s economic policies and boosted Syria’s standard of living.

2. Bereshit 42:1. When Yaakob Abinu sent his sons to Mitzrayim, he cautioned them not to enter together.

3. “Much of the community left during the unification of Egypt and Syria (1958-1961) and settled in Eretz Yisrael, primarily in Gilo. By the mid-1970s there were probably less than 100 Jewish families in Qamishli” (Faraj Nahum).