A Mishna in Kiddushin (25b) mentions mechanisms for acquiring a large animal. Rabbi Meir and Rabbi [Eleazar1] say that is may be acquired via מְסִירָה, passing over the reins which control the animal, while a small animal may be acquired by הַגְבָּהָה, lifting. The Sages argue that a small animal can be acquired even by מְשִׁיכָה, pulling.

The Gemara there relates that Rav proclaimed in the town of Kimchona that a large animal is acquired via מְשִׁיכָה. Shmuel found Rav’s students and expressed wonder that Rav said this. “Doesn’t the Mishna state מְסִירָה? And I’ve heard Rav say מְסִירָה. Did he retract?” Rav’s students (in Sura) explain that Rav indeed retracted, and based himself on a brayta that have the (plural) Sages say both are acquired by מְשִׁיכָה, while (the individual) Rabbi Shimon says that both are acquired via lifting. In Pumbedita academy, third-generation Rav Yosef and fourth-generation Abaye and Rabbi Zeira II debate how Rabbi Shimon’s lifting could possibly work to acquire an elephant. Perhaps that implies that the brayta’s account of the dispute was accepted in both academies. Note also the sound-similarity between מְסִירָה and מְשִׁיכָה.

Rif and Rosh (ad loc.) rule like these Sages of the brayta (וכן הלכתא) that large and small animals are acquired with pulling. I suppose that we disregard Shmuel’s surprise and say he’d also retract, or we’d take the Pumbeditan discussion as an endorsement. Further, Rosh on the Mishna had cast מְסִירָה as the easier acquisition; if it worked, then certainly pulling would work. The seeming halachic conclusion is that מְסִירָה doesn’t work, only pulling.

An alternative may be that pulling works, but so does מְסִירָה. Or, מְסִירָה might work for real estate and items other than animals. See also Bava Metzia 8b, about holding the reins and acquiring an animal, involving many Amoraim, and whether it works for acquiring a found ownerless animal or one previously owned by a childless convert, since there is no one from whom to transfer.

What does מְסִירָה mean? The masorah seems to be that the root is מסר, to convey or transmit. However, compare with the word מוּסָר, which means discipline or morality, from the root יסר, and מוֹסֵר, meaning fetters or restrictions, perhaps related to the root אסר. From the last, we have מוֹסֵרָה, which means reins. In Bava Metzia 8b, regarding the meaning of מוֹסֵרָה, reins, Rava says that Idi explained to him that they are like one who transmits (moser) an item to his fellow. I suspect the technical term taps into multiple senses. We’ll see all instances of מְסִירָה involve transmission of rein-type objects.

Perhaps transmission of reins is a form of chazaka. You control the animal via the reins. Thus, you demonstrate the validity of your relationship to it—just as directing a servant to perform labor, digging pits in a field, or even kinyan biah for kiddushin. Alternatively, for something extremely large, the reins controlling it are akin to a handle, similar to a yad to nedarim.

The Reins of a House

I think that the current sugya, Bava Kamma 51-52, has named Amoraim accepting this מְסִירָה acquisition, even as the Talmudic Narrator doesn’t even recognize the possibility. The Mishna on 51a described two partners to an open בּוֹר (well). The first partner passed by without covering it. Then, the second passed by without covering it. The second is liable. How did the transfer of responsibility occur? On 51b, Rabba and Rav Yosef (third-generation Amoraim, Pumbedita) each cite the same earlier Amora differently: either when the second leaves the first still drawing water, or מִשֶּׁיִּמְסוֹר לוֹ דׇּלְיוֹ, when he hands over (root מסר) the bucket. That version accords with the position of the Tanna, Rabbi Eliezer ben Yaakov II, but the Sages who argue. The Gemara ties this into a global dispute regarding בְּרֵירָה, retroactive clarity, so that each partner draws water from his own portion, but this is explaining whether drawing works, not whether handing over the bucket works.

The Gemara continues by citing Rabbi Eleazar ben Pedat (not ben Shamua, based on context) who says הַמּוֹכֵר בּוֹר לַחֲבֵירוֹ, כֵּיוָן שֶׁמָּסַר לוֹ דׇּלְיוֹ – קָנָה. “One who sells a well to his fellow, as soon as he hands over the bucket, the buyer acquires.” The Talmudic Narrator objects. Real estate is acquired via kesef, shtar and chazaka. There is no document mentioned here, but presumably the buyer paid for it and will eventually utilize it, either of which will transfer ownership. If via money, it was acquired with money earlier. If via chazaka (using the well), the acquisition should happen later! How does conveying the bucket work? The Talmudic Narrator answers that the well is indeed acquired via chazaka, but handing over the bucket is an indication by the seller that he has the go-ahead to perform chazaka.

I’d suggest an alternative. Real estate such as land cannot be practically lifted or pulled, which is why those acquisitions aren’t listed, aside from any derashot about their effectiveness from מִיַּד עֲמִיתֶךָ in Kiddushin 26a. However, if מְסִירָה works, then a handle / controller can be acquired and convey ownership. The control of the well is via the bucket, which is why one partner conveys control and responsibility to the other in this way.

Next, Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi, a first-generation Amora from Israel, says that one selling a house, thus real estate, transfers ownership when he hands over (שֶׁמָּסַר) the key. The Talmudic Narrator objects with the same objection and answers with the same answer. I’d instead respond that the key represents entrance to and control of the house, so it’s the house’s reins.

Second-generation Israeli Amora Reish Lakish cites first-generation Rabbi Yannai that one selling an entire flock transfers ownership when he hands over (שֶׁמָּסַר) the מַשְׁכּוּכִית. Note the root of משכ, to draw / pull2. The Gemara explains that in Babylonia, they explain מַשְׁכּוּכִית as a bell. (Rashi: which he rings before the flock and they follow.) Rabbi Yaakov explains it as the goat which goes at the front of the flock. I’ll associate the two by mentioning a “bellwether”, the leading (castrated) ram which is fitted with a bell. If the flock would indeed follow that belled sheep, then it draws them. Is this performing מְשִׁיכָה on the flock via the bellwether, or is it the reins of the flock?

Yerushalmi Parallel

In Bavli, this sugya only appears in Bava Kamma, and מסר is understood by the Talmudic Narrator as just indicating that the chazaka may take place. Yet, these are Amoraim of the Land of Israel. We might better understand their intent by consulting Talmud Yerushalmi. The Yerushalmi parallels aren’t in Bava Kamma, but in Kiddushin 1:4 upon the aforementioned Mishna which mentioned מְסִירָה, and in Bava Batra 3:1 upon a Mishna discussing chazaka on real estate (via uncontested possession for a period of time).

In Yerushalmi Kiddushin, the Gemara leads with Rabbi Huna, that מוֹסֵירָה only works for the possessions of childless convert. (In Bavli Bava Metzia 8b, it’s Rav Huna who says that it doesn’t work for a found animal/an animal of a childless convert, so we may need to amend.) Then, Rabbi Eleazar ben Pedat asks about 10 camels in a line, each tied to the next. מָסַר לוֹ מוֹסֵירָה שֶׁלְּאַחַת מֵהֶן, if he hands over the reins (here, מוֹסֵירָה), does the buyer acquire just that camel or all of them? The implication is that at least one camel is acquired by taking the reins. The Gemara also discusses the bellwether for a flock and the bucket for a well. Rabbi Yochanan says a house may be acquired by storing something there (chazaka), and other Amoraim discuss whether handing over the key works. Also, Rav Yehuda (bar Yechezkel, second-generation Amora in Bavel) sent to ask Rabbi Eleazar (ben Pedat) how large animals are acquired. He responded, “via מְסִירָה”. He3 asked, “is this not the Mishna, that a large animal is acquired via מְסִירָה” “There are those who switch.” From here, we see that Rabbi Eleazar ben Pedat does maintain the acquisition of מְסִירָה by animals, and it shouldn’t surprise us regarding other items.

In Yerushalmi Bava Batra, Rabbi Yochanan is cited as explicitly saying handing over the key works to acquire the house, not just storing produce. They also mention a bucket for a well and the bellwether for a flock. Many Amoraim overlap with Bavli, though sometimes discussing different cases.

It’s evident from the content (camels) and context (chazaka, mesirah) of these Yerushalmi that Amoraim in Israel regard the reins, bucket, key and bellwether to be an actual means of acquisition, not just a signal that another kinyan should work. In Bavli, if Shmuel were to disagree with Rav about מְסִירָה, he’d have plenty of company. Even if מְסִירָה doesn’t work for animals, it wasn’t ruled out for real estate, even if the Tanna omitted it (תנא ושייר). If we can disagree with the Talmudic Narrator’s explanation, there would be significant halachic ramifications.

Rabbi Dr. Joshua Waxman teaches computer science at Stern College for Women, and his research includes programmatically finding scholars and scholastic relationships in the Babylonian Talmud.

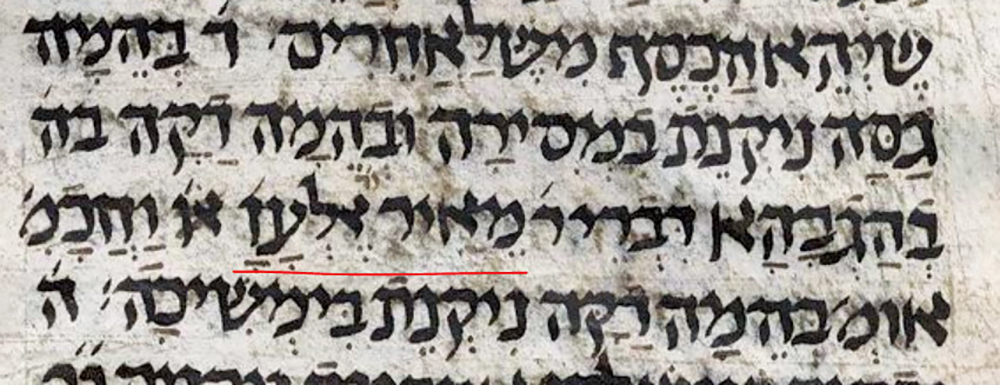

1 Emending Eliezer to Eleazar as found in Mishnayot in the Guadalajara Talmud printing, the print and Leiden manuscript of Yerushalmi Mishna, and the Kaufmann Mishna manuscript. Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus is third-generation, so shouldn’t appear after Rabbi Meir. Rabbi Eleazar is Rabbi Meir’s fifth-generation contemporary.

2 calling to mind the kinyan, though it might not be so

3 There is an intervening אמר ליה but Korban HaEidah and Pnei Moshe disagree as to whether we shift to Rabbi Eleazar here, and whether the subsequent reply is another shift.