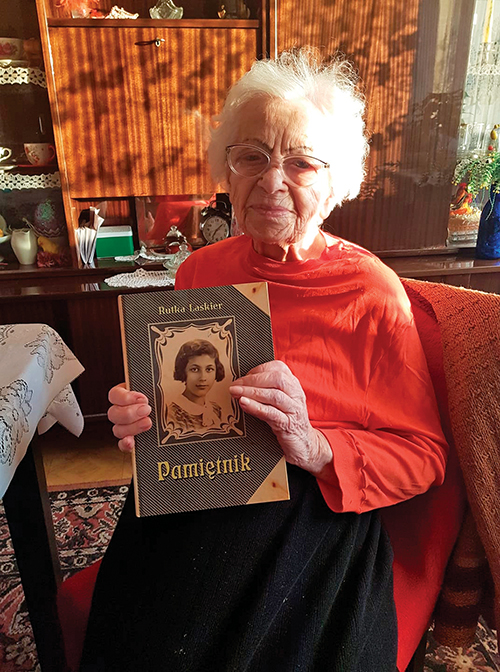

(Credit: Adam Syzdlowski)

Adam Szydlowski, a man on a mission, wants Poles who would rather forget to remember. Recently, at Fair Lawn’s Congregation Shomrei Torah, Mr. Szydlowski shared his passion for Bedzin, its surrounding communities, and Rutka Laskier, considered the Anne Frank of Poland.

Szydlowski’s resume displays his qualifications. He’s the Editor-in-Chief for the municipal paper, an historical consultant for the BBC, ARD (German public broadcasting), and numerous documentaries, Founder and President of the Rutka Laskier Foundation, Founder of the Museum of the Jews of Zaglebie (the Dabrowski Basin of Southern Poland), and Founder, Café Jerusalem (which unfortunately, recently closed). The cost to being so openly philosemitic in Poland, post-October 7th and its aftermath, is an exacerbated, generations-old antisemitism where millions of Jewish perished.

The Demise of a Thriving Jewish Community Pre-WWII

Bedzin had been a prosperous industrial hub with about 27,000 Jews. Many relocated there after WWI, co-existing peacefully with Polish neighbors. In 1939, following Germany’s invasion, Bedzin’s vibrant Jewish life halted. Nazis burned the synagogue, killed over 200 Jews, and seized industrial facilities. Despite this, Jews fared better there than elsewhere in Nazi-occupied areas. Thousands of Jews worked in Christian industrialist Alfred Rossner’s Bedzin factory. He saved hundreds, until the Gestapo hanged him in 1944.

In spring 1943, relocations to the ghetto began. Here Szydlowski pivots to the Laskier family and their daughter Rutka.

Rutka’s Diary

After the invasion, Krakow banker Yaakov Laskier’s family moved in with relatives in Bedzin; in 1943, the family was sent to the ghetto. Stanislawa Sapinska, whose family relinquished their ghetto-situated house to the Laskiers, periodically visited and befriended 14-year-old Rutka. From January-April 1943, Rutka kept a diary about typical “teen” issues—her looks, her clothes, boys—but she also carefully documented life, and atrocities, under occupation. In January/February 1944, Sapinska located a place, where, wedged into the stairs, Rutka could hide the diary.

The ghetto was split in two in 1943; the Laskiers, housed in the smaller ghetto, were sent to Auschwitz/Birkenau. Rutka’s mother Devorah and younger brother Henius perished. Rutka survived until 1944, when she contracted cholera and was sent to the crematoria.

Laskier’s banking experience saved him. The Nazis sent him to Germany, where he and other Jews secretly counterfeited US and British currency (Nazis wanted to flood Allied markets with worthless currency; see The Counterfeiters [2007]). He returned to Judenrein Bedzin in 1945. After the Russians’ 1944 occupation, Sapinska returned home and retrieved Rutka’s diary. Given communist repression and antisemitism, she hid its existence until 2005, when she contacted Szydlowski. He subsequently reached out to Auschwitz’s Museum and other Jewish institutions; none expressed interest in Rutka’s diary.

Szidlowsky asked his Israeli friend, Menachem Lior, to search for surviving Laskiers. After two months, Lior responded that Yaakov had survived, made Aliyah, remarried, and had a daughter, Dr. Zahava Scherz. Until age 14, she knew nothing of his wartime losses, but after seeing unfamiliar faces in photographs, she confronted her father, who acknowledged his first family—and then never again spoke about them.

Szydlowski, registrar of Bedzin’s births, deaths, and marriages, could access some Laskier records. He also had the diary, but no photos; Scherz, who had photos but no diary, sent some to him. He identified and traveled to England to interview Rutka’s best friend Linka Gold, who escaped the ghetto. Gold showed him her notebook, with Rutka’s inscription.

When Szydlowski sent Yad Vashem a copy of Rutka’s diary, it was validated; Sapinska brought the original there and donated it. The 2005 and 2008 editions, edited by Szydlowski and published by Yad Vashem, are in English and Hebrew. Scherz and Szydlowski traveled extensively, to arrange for the diary’s translation into 22 languages.

In 2017, producer Amy Langer contacted Szydlowski about a theatrical version of Rutka’s story. In 2022, he was asked to advise on the show, which premiered to a small, select New York audience that year. It segued to an October-November 2024 run of the youth-focused Rutka: A New Musical at Cincinnati’s Playhouse in the Park, which Szydlowski attended. He invited everyone involved in it to visit Bedzin, which he feels is essential to fully experience and understand Jewish life there in Rutka’s time As yet, no one has visited.

(Credit: Adam Syzdlowski)

The Significance of Rutka’s Diary: What Impact Has It Had on Polish Youth?

The diaries of Rutka and Anne Frank both reveal typical teen anxieties, wonder at adolescent changes, and interest in boys. Rutka’s firsthand account is much more graphic in its depictions of Nazi cruelty.

Scherz visited Bedzin on multiple occasions. Prior to her visit, Polish elementary students, ages 12-13, and their teacher, Rutka’s diary. When she came, they recited excerpts and discussed the diary’s impact on them. For adolescents who are at least two generations removed from WWII, the diary provides an historical perspective previously unavailable to them. In 2010, five of these schoolgirls, accompanied by Sapinska and high school students playing Germans, Poles, and ghetto residents, participated in a street theatre-like, fully costumed reenactment of the ghetto’s evacuation for deportations. About 2000 spectators, residents of Bedzin and vicinity, attended. Szydlowski stresses the need to educate Polish youth, as they are the principal agents of change in attitudes towards Jews. For the past two decades, Szydlowski notes, antisemitic graffiti and open antisemitism has been absent in Bedzin.

The jury is out on the ultimate impact of Rutka’s diary, but as it works its way across the globe, one cannot underestimate how one girl’s moving account of Jewish history, and one historian’s attempt to keep her history and Bedzin’s alive, can affect those who today may question its truths.

Sources

BBC. (2009) Rutka’s Notebook https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YnD_EtHqW44

Laskier, R. (2008) Rutka’s Notebook. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem

Ruzowitzky, S. (2007). The Counterfeiters. (based on Adolph Burger’s The Devil’s Workshop: A Memoir of the Nazi Counterfeiting Operation; Oscar for Best Foreign Language film.

Szydlowski, A. (2010) Reenactment of the Evacuation of Bedzin Ghetto in 1943. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_-ZMIGHb5k&t=69s

Rachel Kovacs, PhD, adjunct associate professor of communication at CUNY, also teaches Judaics locally, and is a PR professional, freelance writer, and theater reviewer for offoffonline.com. She trained in performance at Brandeis and Manchester Universities, Sharon Playhouse, and the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She can be reached at mediahappenings@gmail.com.