Part IV (continued from last week)

Suddenly, I heard the sound of vehicles getting louder and louder. Three tanks were approaching at great speed. Fanya, my older sister said, “Swastikas.” The tanks stopped short in front of us. Two young German soldiers appeared out of the first tank and marched over to us. They took one look at us and said to each other in disgust: “Juden!” (Jews). One of them, who seemed to be of higher rank, said in German: “Let’s not waste our time with them. Somebody else will finish them off!”

They turned away from us and pointed their guns at a lonely Russian soldier walking nearby. They directed the soldier to enter the tank with them. The tanks started to roar and quickly sped off.

We all stood paralyzed for a while, realizing how close to death we had come. “Let’s get off this highway as quickly as possible and into the woods. From now on we will have to move under cover,” Father said, breaking our silence. He pulled the horse off the road.

In the woods we found a sign reading “Berezina.” Herzl pulled the horse in that direction and everyone followed. On this road, deep in the woods, there were Soviet soldiers roaming everywhere in groups and singly, retreating before the coming Nazis. There were also abandoned army vehicles trimmed with branches for disguise. Suddenly, we heard a strange, whining sound above our heads. It couldn’t be: “Messerschmitt” (German fighter planes), one of the soldiers exclaimed. We continued on our journey, more worried now that the Germans would meet no resistance.

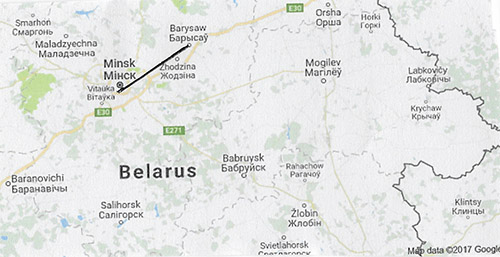

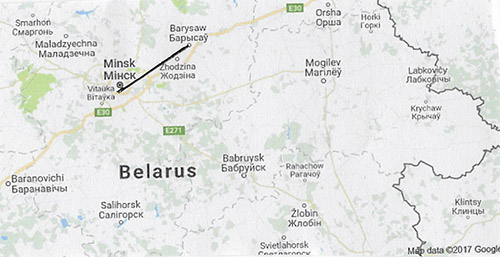

Three days had passed when we reached Berezina, a small town near Borisov (now Barysaw). We knocked on the door of the first house. No answer, but the door was unlocked. Herzl pushed the door open and entered. Inside the house was a dining room with a big table and chairs around it. Plates and glasses were set on the table, with some food on the plates and drinks in the glasses. There was nobody around. The people must have left in a hurry, not finishing their meal.

The second house was also deserted and so was the next and the next. A town without people. We were so tired, that against the judgment of Father and Herzl we begged to stay in town for a couple of hours just to rest a little.

We were passing the school house, and Father finally gave in: “We will stay for a while in the schoolhouse.” I sat down at a school desk. An open book lay before me. A child had printed in it in big letters, “I love flowers,” and drew a picture of a big flower. Where is the child? I wondered. Will he see his flower garden again soon? I shut my eyes. We must have slept for a couple of hours when banging at the windows woke us up. It was very dark in the schoolhouse. “Anybody here?” a man’s voice was asking. Herzl stepped outside. Two men with shotguns came in with him. They called themselves “Russian partisans.” They will remain behind enemy lines and organize the resistance, they told me. We must leave at once and get one of the villagers to take us on the barge over the river, since the bridge over Berezina was blown up by their men. The Germans were coming shortly and there was no time left.

We quickly got moving again, heading for the nearby village. Our father skillfully guided the horse through the woods with us following closely behind. The shades of the tall trees made our journey so much cooler than before, when we were exposed. This served as some compensation for stumbling over stumps and stones. We came to the edge of the woods.

Not far away, we noticed a peasant’s house at the edge of a winding river. Our father stopped the horse and went to the house. Soon he came back with a peasant who looked us over, including the horse and wagon, and nodded. What it meant was that he agreed to take us across this river on the barge that was tied up at the shore nearby. However, to be safe he would only do it under the darkness of night. The peasant’s wife brought out some water with which we washed our faces and hands, and we ate some bread and drank some water.

The day was coming to an end, and darkness set in. It was a moonless night, and soon the peasant motioned to us to get going. He led the horse with the wagon onto the barge and motioned to us to move onto it as well. He loosened the rope and we started moving, our feet feeling unsteady as we moved forward. He used a large oar with such expertise that the barge moved at a good rate of speed. Before we knew it, we were on the other side of the river. Our father went up to the wagon and took out our mother’s Sabbath candlesticks from one of the bundles and gave them to the peasant, who couldn’t stop admiring them. So, that’s what it took to have him take us across the river! Well, it brought us closer to freedom from the Nazis, so it was more than worth it.

Father explained to us: “If we will get to Mogilev before the Germans, we will be able to take a train east and maybe even get to Moscow.”

At daybreak, the horse refused to go further; it just folded its legs and lay down. It seemed the end has come for our horse. My little sister was crying, and Mother was trying to comfort her. And then, miraculously, after a few minutes the horse got up, drank some water and continued pulling the wagon.

The sun was high and we were once again on the highway leading to Mogilev. A few times during that day German planes flew low over the highway, shooting machine guns into the crowds of refugees. Hearing the approaching planes, we all ran into the cornfields where we lay motionless. The Germans kept on shooting and we, in our place of hiding, hoped that none of the family got hit. When the planes left, we got up, all of us unharmed. We thanked God and proceeded on our journey.

A well-dressed young Russian joined our group along the way. He spoke a beautiful Russian and I thought he must be an educated Muscovite or maybe from Leningrad. And then he tripped on a rock and hurt his foot and was unable to walk. I heard him curse, “Donnerwetter,” a curse in German, trying to move his foot. “Let’s go,” I whispered to Father, who was about to help him walk. Father looked at me bewildered. I whispered “a German.” Maybe he was a German spy, sent to mingle with the refugees. We left him on the highway.

It was on the seventh day of our journey when dark clouds covered the sky. It was thundering and lightning and big drops of rain started falling. It was a heavy rainstorm and there was no shelter in sight. Our clothes were soaked, water from my hair dripping all over my face and mixing with salty tears.“How much longer, oh God,” I was asking. As if my plea was being answered, the rain stopped and a rainbow appeared in the sky. The sun came out again and its warmth was so comforting. Shortly, the outlines of a city appeared before us. This was Mogilev, the city we were striving to reach for so long.

(To be continued next week)

By Norbert Strauss,

Dr. Ida (Melcer) Zeitchik and Dorothy Strauss

Norbert and Dorothy Strauss are Teaneck residents. Norbert was general traffic manager and group VP at Philipp Brothers Inc., retiring in 1985. Dorothy worked as a senior systems analyst at CNA Insurance Company. Dr. Ida (Melcer) Zeitchik was Dorothy’s mother.