The sun was shining brightly through the only window in the wall. The room was very large and bare. A clay floor, a round opening in the corner with a big pot on it, served as a stove, but we had a roof over our heads, and we were here to stay.

Shimshi-han arranged our bundles at one wall and sat down next to them. We followed suit, and stretched out our legs, leaning against the bundles. Drowsiness overtook us. I shut my eyes and tried to doze off, but sleep didn’t come easily. I felt as though I was still on the freighter, listening to the children next to me asking their mother for food and hearing her respond, “Be patient, soon they will bring us bread.”

Shimshi-han and her mother brought in a large straw mat, which they spread on the floor. A Persian rug could not have looked prettier, or softer. We tried to thank them, but only Shimshi-han understood some Russian and tried with great difficulty to be our translator. They both bowed to us and beckoned us to follow them into their “apartment.”

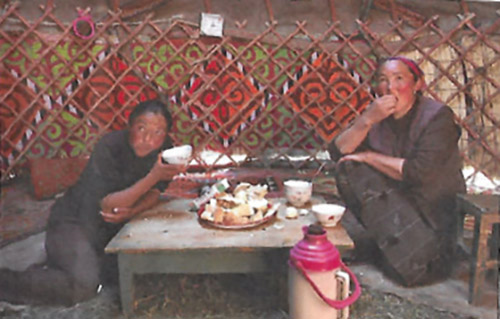

The mother and Shimshi-han lived in one room with one window in the corner. They had given us the second room, which must have been the children’s room. I noticed a little boy playing with some wooden animals at a low table placed in the center of the room. A few minutes later an older man came in. His hair was white, which made him look much older than he actually was. There was sadness in his eyes. Food was served, some very thin noodles and cheese.

Shimshi-han made sure we got generous portions. Her mother served strong tea. When we thanked them they smiled at us, conveying a feeling of great compassion. The woman brought out a photograph of a young man in a soldier’s uniform. He had his mother’s gentle smile and his father’s sad eyes. All at once they all started crying, tears rolling down their cheeks, and we understood. This was their son and brother, fighting the Nazis at the front.

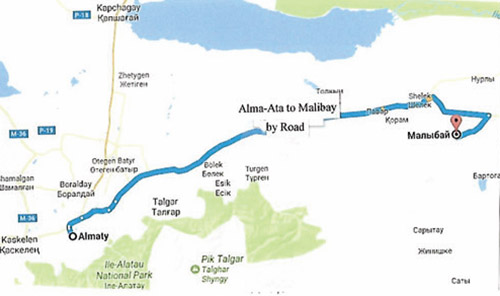

The mother pointed to the photograph and to her heart, she was trying to ask us if somewhere along our journey we came across her boy. Did he direct us to Malabay? Did he tell us to come here to them?

We all sat very quietly; we had no answers to her questions. She sighed deeply and wiped her eyes with the sleeves of her dress. The glow went out of her eyes. All became very quiet, and seemed to be losing the sparks in their eyes as well.

Dinner was over. The woman got up and carefully put away the precious photograph. She walked over to a corner in the room, where a pile of blankets was stacked up. She took a large, beautiful patch blanket and gave it to my mother.

In response, my mother tried to bow the way the Kazakh woman did, but she looked very awkward. My brother Herzl took the blanket from her and bowed respectfully. We left for our room, very touched by our hosts’ kindness, and at the same time terribly saddened.

Father was the first to speak up. “They are wonderful people, but we don’t know their language, and we can’t even say thank you.” “Rahmed is the word,” said my 10-year-old sister, Sima. She heard Shimshi-han saying it to her mother when she gave her an extra portion of noodles. My older sister, Fanya, repeated “rahmed” twice and commented, “It’s a beautiful word.”

I always knew she had good taste in clothes, but as for language, I was supposed to be the future linguist… I let it pass this time. I knew that I may as well forget my former plans and hopes. The only thing that was left now was to survive, and maybe one day the war will end and a flying carpet will appear to take us back home. “It’s getting dark,” said Father, “so let’s make it a night.” I was jolted back to reality.

We lay down next to each other, on the straw mat, some clothing under our heads for pillows, and spread the patch blanket over us. It almost covered six people. She must have given us the largest blanket she owned, I thought. Is there anything we could give her? But I couldn’t come up with anything that we owned that would match the woman’s gift. It was my first peaceful night since we had left home.

When I woke up it was still dark. The wind was blowing through the open window, a dog was barking in the distance.

It must have been very late when we woke up the next morning. Someone was knocking at our door. Shimshi-han, in her broken Russian, asked us to come outside. The sun was high in the sky. It was a cloudless day, with a hot wind blowing. Shimshi-han’s mother was kneading bread on a cloth spread out in the yard. Nearby, in the earth, was a stove. It looked like the round pot in our room, but it was much larger. Smoke was coming out of it; the wood was burning. We watched while Shimshi-han was helping her mother make large, flat, round “breads.” When the fire was out they pasted the flat breads (“leproskas”) on the sides of the stoves, and in a very short time the beautiful breads were ready. The first leproska was divided between us and some onlookers (neighbors’ children). Nothing I ever ate tasted as good as this first piece of bread in Kazakhstan.

From then on, whenever bread was baked in the yard, we all made sure we were there. The women always offered us pieces from the first leproska. This was a custom observed here. The same afternoon we were given our ration of flour for a week, and Shimshi-han’s mother taught us how to bake bread outside.

That day, Father went to the market and exchanged two of his handkerchiefs for bran. He learned this was the way of trading here. Russian rubles were taken in the marketplace with great resistance; we didn’t have them anyhow. We mixed our next allotment of flour with bran, which produced more bread. It was not as tasty, but just as filling. Later on, when the Kolkhoz decided to cut off our flour allotment, our bread consisted only of bran lepruska, baked after mixing the bran with boiling water. Kolkhozes were collective farms where the farmers planted corn and potatoes.

Malabay had five Kolkhozes, and the Kolkhozniks were allowed a small patch of a field next to their house and one cow. The earth had to be irrigated with canals dug by the owner of the field. The water ran in the mountain streams and it was hard work to bring it down to one’s garden. From these canals the water was brought in to the house for drinking, washing and bathing.

The pastures in the village were poor, and the cows gave about a glass of milk a day. From the accumulated milk, butter was beaten in a glass bottle. Yogurt was also made, and sold at the bazaar. The people also got some income from the apples and apricots that grew near their homes. They dried the apples and apricots on the flat roofs of their homes, and after leaving some for themselves, sold them at the bazaar.

(To be continued next week)

By Norbert Strauss, Dr. Ida (Melcer) Zeitchik, Dorothy Strauss

Norbert and Dorothy Strauss are Teaneck residents. Norbert was general traffic manager and group VP at Philipp Brothers Inc., retiring in 1985. Dorothy worked as a senior systems analyst at CNA Insurance Company. Dr. Ida (Melcer) Zeitchik was Dorothy’s mother.