Some messages are simply too important to miss. One such message, I believe, emerges from two words in the Talmud’s short discussion of the Chanukah festival. While overwhelmingly vital and powerful, however, this communication is easily missed. We have to be sensitive enough and honest enough to note it.

After briefly describing the Hasmonean victory over the Syrian Greeks and the miracle of the sole remaining cruse of oil, the Talmud states: “L’shana acheret, to another year, [the rabbis] established and rendered [these eight days] permanent festival days with praise and thanksgiving.”

The Talmudic record is clear. Chanukah is not established immediately as a festival, but only in conjunction with “another year.” Faced with this assertion, many commentaries render the phrase l’shana acheret as “to the next year.” Chanukah is established as an ongoing festival, these scholars maintain, one full year after the Hasmonean victory and the rededication of the Temple—once the rabbinic authorities recognize the full significance of the events that have transpired under their watch.

If this is the case, however, why doesn’t the Talmud use the specific language l’shana haba’a, literally, “to the coming year”? Even if Chanukah is established only a year later, might the rabbis be teaching us a lesson through their use of the broader phrase l’shana acheret?

A potential answer can be gleaned from the powerful observations of Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik (the Rav) concerning Judaism’s approach to time. This great scholar identifies three dimensions of “time awareness” as essential to the life of each Jew: retrospection, anticipation and appreciation.

Retrospection refers to man’s ability to re-experience the past in the present. What for others is only a memory, the Rav maintains, must become for the Jew a “creative living experience.” To lead meaningful Jewish lives, our personal journeys must be actively shaped by the events, and populated by the personalities, of our people’s past.

Anticipation, according to the Rav, speaks of man’s projection of visions and aspirations into the future. Within this dimension, the Jew enters the realm of foresight and expectation. He recognizes the need to act now, in order to propel his dreams, and his people’s dreams, forward.

The third and final dimension of time-awareness, appreciation, is the most crucial of all. Here, the challenge is to recognize the unique nature of the here and now. So central is the dimension of appreciation, according to the Rav, that it lends meaning to the other two. “Retrospection and anticipation are significant only insofar as they transform the present.” The past and future are valueless to the Jew, the Rav maintains, unless they affect the way he/she acts now.

To go one step further, we might argue that appreciation is not only the most central of the three dimensions of time-awareness, but also the most difficult one to enter.

To fully “appreciate” our times, we must learn to view our lives through the lens of history. The stipulations of appreciation thus form a fundamental imbalance: we must judge ourselves as we will be judged in the future, but we must render that judgment now. We are challenged to ask ourselves: One hundred, 200, 500 years from now—how will our generation’s story and our generation’s contributions to Jewish life be measured? Clearly, these are difficult questions to answer. Lessons from the past are easily accessed through hindsight. Visions of a glorious future are readily imagined. A true assessment of present opportunity, challenge and performance, however, can remain elusive. Such appraisal often seems to need the perspective granted by a shana acheret, another year. And waiting for a shana acheret is a luxury that we can generally ill afford.

In our day, few within the committed Jewish community would argue with the fact that the establishment and development of the State of Israel has been a transformative event, unequaled in thousands of years of Jewish history. With the passage of time, however, one senses that a full appreciation of what Israel continues to mean has begun to fade…

Unfolding before us is a continuing grand experiment, replete with innumerable, ever-shifting facets: the ongoing return of a dispersed people from across the globe to its ancestral homeland; the cobbling together of disparate populations, vastly different from one another, into a working, functioning, governable democracy; the blending of Jewish tradition with democratic principle; the unaccustomed use of power by a people powerless for centuries; the forging of an ever-changing relationship between Diaspora Jewry and Israeli citizenry; the rapid rise of the new-born state into an economic powerhouse; the development, by necessity, of an ever-adapting, world-class, powerful military and security apparatus; the positive changes wrought in the psyche of Jews across the globe because of the very existence of a Jewish state; and so much more…

A full appreciation of these extraordinary realities means that our lives as Jews, wherever we may live, should be fundamentally transformed by their existence. Jewish past and future converge on the present, and we are asked by history: How will your lives and the lives of your children be different because Israel exists?

For some, this question might lead to a real consideration of aliya, so that they and their children can most actively be part of the greatest experiment in thousands of years of Jewish history. For others, it may lead to keeping aliyah on the agenda, even if the move is not possible now. And for others, it may lead to a strengthening of their awareness and involvement, to an active search for ways to attach their daily lives and the lives of their children to the unfolding miracle of our day.

After all, the verdict is still out. Just as the Zionist pioneers could never have predicted in 1948 what Israel would look like in 2018, none of us can imagine the Israel that might greet our eyes, 10, 20 or 70 years from now. Given that reality, how can any of us fail to play a part of the continued shaping of the Jewish state, the central story of our people in our time?

Centuries ago, the Hasmonean revolt saved Judaism, only to ultimately fall victim to its own excesses and lost perspective. Could the Talmud be hinting at one of the reasons? Perhaps the rabbis are teaching

us that had our ancestors recognized the importance of the Chanukah victories immediately, and not l’shana acheret, they would have successfully retained their footing in a turbulent world.

If we learn to appreciate the gifts divinely granted to us in our day, perhaps this time we will also successfully rise to appreciate the challenges they bear. And perhaps we will meet those challenges while there is still time, l’shana ha’zot, to this year.

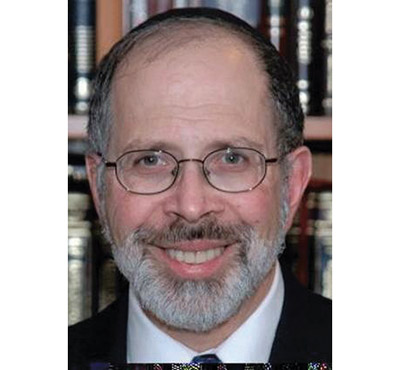

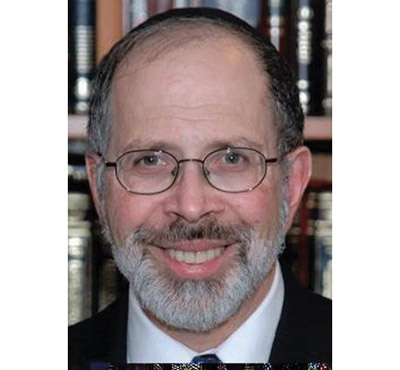

By Rabbi Shmuel Goldin

Rabbi Shmuel Goldin currently serves as Senior Scholar at Nefesh B’Nefesh. He previously was the spiritual leader of Congregation Ahavath Torah in Englewood, New Jersey, for over 33 years and still serves as Rabbi Emeritus of that Congregation. He served for over twenty years as instructor of Bible and Philosophy at the Isaac Breuer College and the James Striar School of Yeshiva University and continues to appear as a visiting scholar and lecturer in a wide variety of settings across the globe. Rabbi Goldin is a Past President of the Rabbinical Council of America (RCA), the world’s largest association of Orthodox rabbis, and, among other positions, occupied the critical role of chairman of the committee reviewing he RCA’s policies and standards for conversion to Judaism. He made Aliyah with his wife Barbara in September 2017, joining two of their children already residing in Israel.